David Raymond Amos @DavidRayAmos

Replying to @DavidRayAmos @Kathryn98967631 and 49 others

BruceJack Speculator

"chemistry does not really depend on the language of the doer and doubling the number of administrators or supervisors definitely reduces the number of technicians that can be paid"

https://davidraymondamos3.blogspot.com/2020/01/moncton-hospital-overcrowded-asks.html

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/new-brunswick/hospital-laboratories-consolidation-flemming-higgs-1.5415021

Facing staffing crunch, province could slash number of hospital labs by more than half

Government issued call for proposals that would consolidate 20 labs into as few as 7

· CBC News · Posted: Jan 06, 2020 7:00 AM AT

The provincial government has issued a request for proposal to develop a plan to consolidate hospital lab work. (CBC)

The New Brunswick government is looking at ways to centralize hospital laboratories, including a proposal that would see the number of facilities slashed by more than half.

A request for proposals issued Nov. 21 is aimed at finding private-sector management consultants who can develop a plan to consolidate 20 hospital labs into as few as seven.

It says the rationale for closures and centralization is not saving money but responding to a "human resource crisis" that will see 40 per cent of medical laboratory technologists eligible for retirement in the next five years.

"Current supply is not able to keep up with attrition rate due to retirement," the document says. "Concerns are also being raised as to the significant knowledge gap resulting from these retirements."

The document refers back to a 2013 report that "identified opportunities for improvement through reorganization."

That report, obtained by CBC News through a right-to-information request, recommended the closure of labs in smaller hospitals and health centres in Miramichi, Saint John, Waterville, St. Stephen, Sussex, Oromocto, Sackville, Minto, Plaster Rock, Grand Falls, Saint-Quentin, Dalhousie, Caraquet, Lameque and Tracadie.

Those services would be "integrated" into labs in seven larger hospitals in Moncton, Saint John, Fredericton, Edmundston, Campbellton and Bathurst, the report said.

Minister hinted at need for consolidation

Health Minister Ted Flemming was not available to comment on the request for proposals, which has a Jan. 7 deadline.

But in a November scrum about the temporary closure of some patient services at the Campbellton hospital, Flemming cited laboratories as a service that could be centralized without affecting patient care, possibly with just two provincial labs.

Health Minister Ted Flemming says centralizing lab work would not impact care. (CBC)

"If you go to a facility and you have your blood taken, what you want to know is your cholesterol and your blood sugar and the usual things that they do," he said.

"What does it matter that that isn't done in one or two centralized areas, one in Vitalité and one in Horizon, for example?

"This doesn't impact care. This doesn't compromise anything. We have an extremely efficient courier system so why do we need 20 labs with 20 people figuring out what people's cholesterol is?"

We're running out of people. There is a storm gathering here.

- Health Minister Ted FlemmingFlemming made the comments the same day his department issued the request for proposals, though he didn't mention the RFP.

He referred to the same difficulty of recruiting enough staff cited in the document. "We're running out of people," he said. "There is a storm gathering here."

An aging population requires more health care at the same time there are fewer working-age New Brunswickers to fill jobs, he said.

"Realistically, this is what we have. These are the people, these are the demands and we have to rationalize what we're doing." Lab consolidation "is an example of types of rationalization that need to be done and that we're going to do."

Short-term fix

The union representing more than 400 lab technologists said it is relieved the province hasn't opted for privatization and said it won't necessarily oppose the consolidation.

"We were kind of in favour of that versus the privatization as long as it wasn't disruptive to the workers," said president Susie Proulx-Daigle, adding some lab samples already move between hospitals for specialized testing.

She said her goal will be to ensure no lab employees are laid off or forced to move to another location while the plan is put in place.

Union president Susie Proulx-Daigle said she wants to ensure no lab employees are laid off during a potential consolidation. (CBC)

"If they're going to do a change, as long as it benefits everybody, and it's good for the public, the consumer, the people who need the service, then we're going to work with them to try to make sure that it works," she said.

She warned though that consolidation will only be a temporary solution and that the same recruitment issue will rear its head again after consolidation. "This will only work for a few years," she said.

According to the 2013 report, the government began looking at lab services as far back as 1997. But a consultant's recommendations made at the time remained "relatively dormant" until the health department raised the issue again in 2012.

The 2013 report said new technology and a focus on preventative care will make detecting disease more important, causing lab testing to "sky rocket" in the coming years.

Labs will have to be "lean, efficient and productive with the ultimate outcome 'increase value for their customer,'" the report said.

It looks at a number of options, including creating a new "shared laboratory services corporation" or privatizing the service completely. A section on "other potential opportunities" is blacked out.

But the report recommended the service remain under the health authorities, with seven labs to service the province.

There would be three labs in southern New Brunswick hospitals, two of them providing specialized testing, one for all of the Horizon health authority and the other for Vitalité.

It said two smaller "reference labs" and two "rapid response" labs would remain in the north.

A 2013 report recommended reducing the number of hospital labs to seven to service the entire province. ((CBC))

The recent request for proposals says a second report in 2018 made recommendations as well, but those are not available publicly.

The RFP says developing an implementation plan would take a year and putting it into effect would take another two years.

It says consolidation will require greater "collaboration and interconnectivity" within the two regional health authorities and between them.

Their labs now use eight different health and lab information systems with "minimal communication and inconsistent definitions and nomenclature." Part of the consulting firm's job will be to address and develop a new transportation system for moving samples.

Premier says major health reforms coming

The two regional health authorities were told last Aug. 12 that the RFP was coming.

"Horizon Health Network has been working closely with the Department of Health and Vitalité Health Network to improve our laboratory services and are aware of the RFP that has been issued," Horizon vice-president Gary Foley said in an emailed statement.

"We look forward to working collaboratively with our health care partners to adapt our services to meet the laboratory service needs of our province."

No one from Vitalité was available to comment.

Premier Blaine Higgs said last fall his government would unveil details of major health reforms in the first three months of 2020.

"I hope to be able to communicate in a way that people understand the rationale behind everything we do," he said in a year-end interview. "I would never suggest that means everyone will like it. It's just that they'll understand why."

With files from Shane Magee and Karissa Donkin

67 Comments

David Raymond Amos

"No one from Vitalité was available to comment."

Surprise Surprise Surprise

Ben Haroldson

Reply to @David Raymond Amos: They were working. Too busy.

Terry Tibbs

Reply to @Ben Haroldson:

In so-called "meetings" not to be disturbed more like.

Denis LeBlanc

It like this is the beginning of the end for many local hospitals. How will the be able to run an emergency ward without a lab? I can see this for routine tests like cholesterol or blood sugar as long as the blood can still be taken locally. Speaking of this...why should you need a lab tech to sample blood? Couldn't a nurse or nurse practitioner do this and free the lab techs to do the analysis? Finally, we are beginning to see the short sightedness of centralizing a lot of services in big regional center when they can no longer handle the load. Furthermore, what happens when one of these super labs is closed down by some sort of emergency, contamination, epidemic or catastrophy? What then? Does the system collapse for a few weeks? How about some unknown illness outbreak in a town or city? You risk spreading the illness to one of the main cities or hospitals in the province. Do you really think it is worth it because of poor planning, pay, benefits and staffing levels already imposed on hospitals?

Ben Haroldson

Reply to @Denis LeBlanc: Wholesale privatization. Anti constitutional, the lib way.

Ray Bungay

Reply to @Denis LeBlanc: Union protectionism IMO!

David Raymond Amos

Reply to @Denis

LeBlanc: "It like this is the beginning of the end for many local

hospitals. How will the be able to run an emergency ward without a lab?"

BINGO

BINGO

Chuck Stewart

Less young people want to work in the health care of the public sector. The system is broken and it is the fault of the society. Hospitals are run by government who are always looking to satisfy the voters, therefore there is no doing what is right , instead it is down to doing what is popular. Higgs is the first premier to try to do what is right and not worry about the votes. The equipment is all there, but with nobody to run it, what can you do. If I was a lab tech, I would not encourage any young person to go into public health care in this province right now. It is very frustrating to see how tax money is wasted.

Terry Tibbs

Reply to @Chuck Stewart:

"I would not encourage any young person to go into public health care in this province "

Because of the crap working conditions and wages.

But get educated here, and move away, and get instant employment, great benefits, and excellent wages.

"I would not encourage any young person to go into public health care in this province "

Because of the crap working conditions and wages.

But get educated here, and move away, and get instant employment, great benefits, and excellent wages.

Joe Mufferaw

Reply to @Terry

Tibbs: I don't think you are correct here Terry. Lab Techs in BC make 2

bucks an hour more than NB. Wages are not the problem in Heatlh care.

The problem is that most open position are either casual or part time.

That is why people move away. Hire full time and they will stay.

David Raymond Amos

Reply to @Joe Mufferaw: Good point

Gary MacKay

It will be interesting to see how this progresses. I recall Previous Premier Frank M. Trying to join the two labs in Moncton and make one to save a significant amount. That was dropped rather quickly. Some how we have to find ways to reduce. Hopefully they can work together to make things more efficient. Truly we really only need one health authority. IMO

BruceJack Speculator

Reply to @Gary

MacKay: agree. I know this is naive of me to say but chemistry does not

really depend on the language of the doer and doubling the number of

administrators or supervisors definitely reduces the number of

technicians that can be paid from the same $ of budget

David Raymond Amos

Reply to @BruceJack Speculator: Speaking simple truths cannot be naive

Ben Haroldson

Reply to @Gary MacKay: This place is living with frankies legacy. Lovely ain't it?

John Holmes

Now that's a page straight out of the UCP playbook. This most certainly won't end well, not when the health care in this province is already slower than molasses.

Johnny Horton

Reply to @John Holmes:

I do not find the health care system slow. Of course I don’t clog up the system with sniffles. When I go it’s something thst needs fixed. Usually within a week of a trip to emerg, I’m booked and in any needed surgery or work.

Ben Haroldson

Reply to @Johnny Horton: You get surgery often?

Johnny Horton

Reply to @Ben Haroldson:

When needed yes. Surgery doesn’t always fix an issue. Thst is worded wrong... surgery doesn’t fix the underlying problems thst led to surgery, still worded wrong but better.

If one jumps out of planes without a chute, surgery will fix the broken bones, but one can just go do it again :)

When needed yes. Surgery doesn’t always fix an issue. Thst is worded wrong... surgery doesn’t fix the underlying problems thst led to surgery, still worded wrong but better.

If one jumps out of planes without a chute, surgery will fix the broken bones, but one can just go do it again :)

John Holmes

Reply to @Johnny

Horton: I waited over a year for a heart test that my Doctor scheduled

for me. And when I showed up, they told me the person who did the tests

was off sick, and it was the wrong test anyways. THE person who did that

test. One person. Think about that. If anything illustrates how bad

staffing levels are in this province, that does it.

I'm stupidly stoic about my health, I generally don't go near a medical person unless I'm on deaths door, or feel like I am.

I'm stupidly stoic about my health, I generally don't go near a medical person unless I'm on deaths door, or feel like I am.

David Raymond Amos

Reply to @John Holmes: "I generally don't go near a medical person unless I'm on deaths door"

Me Too and when I do I have to pay for the Health Care because Higgy and and his cohorts put a so called "Stay" on my Medicare Card

Me Too and when I do I have to pay for the Health Care because Higgy and and his cohorts put a so called "Stay" on my Medicare Card

Johnny Horton

Reply to @David Raymond Amos:

That’s what ya get for leavin the country.

Johnny Horton

Reply to @John Holmes:

Well one could say if you waited a year for a test, then the test really wasn’t an emergency. You certainly didn’t die in thst waiting yesr.

Well one could say if you waited a year for a test, then the test really wasn’t an emergency. You certainly didn’t die in thst waiting yesr.

Joe Mufferaw

Reply to @Johnny

Horton: You must live in Moncton, Fredericton or Saint John. My

daughter has been waiting a year to get her tonsils out become they

affect her breathing. Once it does happen we have to go to Moncton and

stay in town for 7 days. Good thing you don't take up space in

emergency and only go for important stuff.

David Raymond Amos

Reply to @Joe

Mufferaw: Methinks the Irving shill has to go to the emergency room to

get his foot removed from his mouth and by his own words it appears to

happen way too often N'esy Pas?

Danny Devo

With conservatives making decisions, conditions are sure to deteriorate. They always do. When things become completely dysfunctional, they resort to their corporate buddy system, hiring friends and family to provide private health services, just like that clown in Alberta is doing.

David Peters

Reply to @Danny Devo:

That's problem is endemic to monopolies, whether they're public or private.

That's problem is endemic to monopolies, whether they're public or private.

BruceJack Speculator

Reply to @Danny Devo:

surely you jest . . . did you mean to say "politicians" instead of

"conservatives" or did you never read about, recent example, the

"shipyard" in Bas Caraqet, or the numerous attempts to build a

campground in Shediac rather than clean up the water or ... or ... or ?

David Raymond Amos

Reply to @BruceJack Speculator: Interesting expression

Lou Bell

The " Centralized Laundry " worked so well !! NOT !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

David Raymond Amos

Reply to @Lou Bell: Methinks you should remind us of your work within our Health Care System N'esy Pas?

Stephen Blunston

here a novel idea lets save millions or billions and get rid of the duplicate system and actually make something bilingual in this province and have 1 not 2 systems

David Raymond Amos

Reply to @stephen blunston: Dream on

Kevin Archibald

Is it possible that a N.B. Premier is really fiscally responsible ? First time in my life, and I'm 59. Go Higgs.

Fred Brewer

Reply to @Kevin

Archibald: I guess you are forgetting about the Liberal Premier Frank

McKenna. He was Premier of NB from 1987 to 1997 and was the first

premier in 13 years to actually start paying off our debt and brought

our fiscal house into order.

Fred Brewer

Reply to @BruceJack Speculator: Yes. He reduced the size of the civil service, reduced services and unilaterally imposed a wage freeze on unions and yet the voters kept him in office for 3 terms. This is proof that the average voter understands the need for fiscal restraint even if it means we must endure some hardships. McKenna created over 6,000 call centre jobs during his tenure as Premier.

David Raymond Amos

Reply to @Fred Brewer: Say Hey to to your buddy Franky for me will ya?

https://twitter.com/

David Raymond Amos @DavidRayAmos

Replying to @DavidRayAmos @Kathryn98967631 and 49 others

Content disabled

Enjoy

https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/230098/000113031902001603/m08476e18vk.htm

Methinks folks should read Minister of Finance Paul Martin's report for the Corporation known as Canada to the Yankee SEC in December of 2002 N'esy Pas?

https://davidraymondamos3.blogspot.com/2020/01/moncton-hospital-overcrowded-asks.html

#nbpoli #cdnpoli

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/new-brunswick/moncton-hospital-overcapacity-1.5415259

Moncton Hospital overcrowded, asks people to seek alternatives

Horizon recommends calling Tele-Care, visiting a pharmacist or family doctor, or going to clinic

CBC News · Posted: Jan 04, 2020 5:42 PM AT

Horizon Health Network said the public should rethink their options for care before going to Moncton Hospital's emergency room. (CBC)

Horizon Health Network is urging people

in Moncton and surrounding areas to rethink their options for care

because the Moncton Hospital is overcrowded.

On Saturday, Horizon tweeted that patients looking for care should visit sowhywait.ca to determine if their symptoms are severe before going to the emergency room.

"If you're in the ER and you need to be admitted, right now they're going to have problems finding beds," said Lynn Meahan, a spokesperson for Horizon Health Network.

Options for care include calling Tele-Care by dialling 811, visiting a pharmacist or family doctor and going to an after-hours clinic.

Meahan said people could be looking at a 12-hour wait if they go to the hospital for something like a sore throat.

There are 24 acute care and trauma beds in the emergency unit — all of which are occupied, said Dr. Ken Gillespie, chief of staff at the Moncton Hospital.

Gillespie said it's hard to pinpoint why the Moncton Hospital has experienced an increase in patients.

"People have been on holidays, maybe they've been putting things off a little bit," Gillespie said.

"A lot of the family doctors' offices are closed over the holidays so they don't have access to that and now they're having a deterioration in their symptoms and they want to get things looked at."

The Moncton Hospital also faced overcrowding last year when patients were taking up beds while awaiting another level of care.

On Saturday, Horizon tweeted that patients looking for care should visit sowhywait.ca to determine if their symptoms are severe before going to the emergency room.

"If you're in the ER and you need to be admitted, right now they're going to have problems finding beds," said Lynn Meahan, a spokesperson for Horizon Health Network.

Options for care include calling Tele-Care by dialling 811, visiting a pharmacist or family doctor and going to an after-hours clinic.

Meahan said people could be looking at a 12-hour wait if they go to the hospital for something like a sore throat.

Beds all in use

There are 24 acute care and trauma beds in the emergency unit — all of which are occupied, said Dr. Ken Gillespie, chief of staff at the Moncton Hospital.

Gillespie said it's hard to pinpoint why the Moncton Hospital has experienced an increase in patients.

"People have been on holidays, maybe they've been putting things off a little bit," Gillespie said.

"A lot of the family doctors' offices are closed over the holidays so they don't have access to that and now they're having a deterioration in their symptoms and they want to get things looked at."

The Moncton Hospital also faced overcrowding last year when patients were taking up beds while awaiting another level of care.

84 Comments

Commenting is now closed for this story.

David Peters

There could be an opt out option. Opt out of medicare and have all medical expenses as a tax write-off.

Free market solutions, including competition, produce goods and services better, faster and cheaper. Why wouldn't this work in the healthcare sector too?

David Raymond Amos

Reply to @David

Peters: Methinks many would agree that Horizon Health Network is just

another Crown Corp with way too many overpaid bureaucrats who are

playing games with politicians over our money and our health N'esy Pas?

John Pokiok

Reason for this is little known issue how doctors in NB hospitals are payed for. They are paid the same weather they see 1 or 10 Patients. They need to be paid per patient and than you will see the difference. Right now they sit around nurses are flicking their phones because doctors dictate how many people they admit per hour, and people are waiting in waiting area for hours you don't believe me ask someone that works there.

David Raymond Amos

Reply to @John Pokiok: They are paid per patient

Jef Cronkhite

Reply to @John Pokiok: yeah, I don't know where you get that information, but it is incorrect.......

Bob Smith

Reply to @John

Pokiok: You might want to check the salaries posted by NB physicians

online first. More than a few see a lot of patients whether they are

family doctors or specialists.

David Raymond Amos

Methinks it is fairly obvious that this is not news to Higgy and his cohorts N'esy Pas?

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/new-brunswick/georges-dumont-hospital-capacity-1.5060707

Greg Miller

About four years ago my son had a sore throat and because of his medical history and the fact the he didn't have a doctor in Vancouver he visited a hospital emergency room. A doctor saw him about 15 minutes later -- AND APOLOGIZED FOR THE WAIT! P.S. My son moved to Vancouver recently and had no difficulty getting a family doctor.

Troy Murray

Reply to @Greg Miller: Great news

David Raymond Amos

Reply to @Greg Miller:

I am very grateful to have a family doctor in NB and pay for his

services out of pocket even though I am entitled to Medicare just like

your son is in BC. Less than a month ago I reported to emergency room

of the Dr. Georges-L.-Dumont hospital in Moncton in order to have some

scheduled tests of my old ticker ordered by another doctor. However the

lady registering me gave me a hard time keeping my appointments because I

did not have a Medicare Card and demanded that I apply for one through

SNB ASAP.I told here I had been there and done that long ago. She had

no answer for me when I asked what concern was it of hers as long as I

paid the Vitalité Health Network bills. For the record last fall in

order to run again in Fundy Royal I had to register with Elections

Canada with the address printed on my meds because of SNB's deliberately

incompetent behaviour. Go figure why I am angry with the malicious

actions of my political foes against me.

Bob Smith

Doesn't help when the hospital has two floors of beds dedicated to seniors awaiting placement in long term care facilities. It's a situation that has existed since before the eighties and got worse over the decades since. The politicians and hospital executives will use the familiar platitudes of "looking into the situation/evaluating the matter.." and so on but no one will try and make a dent in it. Why? No money or backbone to change the status quo...

David Raymond Amos

Reply to @Bob Smith:

At least all the politicians and bureaucrats who have no backbones have a

Medicare Card. Ask yourself why Higgy and his cohorts won't give me

mine so that I have to pay when I visit the emergency room to have my

old ticker tested.

Bart JW

Reply to @Bob Smith: So what is the solution in your opinion? More money has not worked.

Pierre Cyr

Reply to @Bart JW:

There hasnt been more money there has been cuts per capita on average

per patient over age 65 who are the biggest consumers of health as the

population has aged. The system is constantly being asked to do more and

treat more patients with less.

Bob Smith

Reply to @Bart JW:

More money where? Building more senior homes has been way behind demand

for just as long. Add that to the problem they don't have nurses hired

to staff the hospitals and there's two flaws. A solution? Maybe start by

financially helping families to care for their elderly loved ones at

home rather than in hospitals where possible. Status quo is not working

and kicking this can down the road is only making it worse.

Greg Miller

Reply to @Bart JW: Solution? Move to another province and chose which one you go to carefully.

David Raymond Amos

Reply to @Greg Miller: How about mentioning my name to Higgy before I sue the Crown again?

Jim Cyr

Reply to @This

is absolutely neanderthal. And it keeps happening over and over,

throughout the province. (Or similar problems). Canadians always brag

about their socialized medicine.....then crap like this happens.

David Raymond Amos

Reply to @Jim Cyr: Who do you blame for this nonsense?

Allan J Whitney

Quite a few things have disappeared down the old memory hole.

Like that document "The IMF's Structural Adjustment Programme for Canada 1994- 1995", received by the Paul Martin government, which outlines the necessity of offloading government expenditures to the private sector (privatization). They actually recommend cutting the funding to certain programs in order to CREATE THE OUTCRY for privatization.

David Raymond Amos

Reply to @Allan J

Whitney: Methinks folks who seek the truth should read the report of

Paul Martin as Minister of finance to the the Yankee SEC in December of

2002 for the Corporation known as Canada N'esy Pas?

David Raymond Amos

Content disabled

Reply to @Allan J Whitney: Enjoy https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/230098/000113031902001603/m08476e18vk.htm

FORM 18-K

For Foreign Governments and Political

Subdivisions Thereof

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

Washington, D.C. 20549

ANNUAL REPORT

of

CANADA

(Name of Registrant)

Date of end of last fiscal year:

March 31, 2002

SECURITIES REGISTERED*

(As of the close of the fiscal year)

| Time of Issue | Amounts as to which registration Is effective |

Name of exchange on which registered |

||

N/A

|

N/A | N/A | ||

Name and address of person authorized to

receive notices

and communications from the Securities and

Exchange Commission:

HIS EXCELLENCY MICHAEL KERGIN

Canadian Ambassador to the United States of

America

Canadian Embassy

501 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20001

Copies to:

BILL MITCHELL

Director Financial Markets Division Department of Finance, Canada 20th Floor, East Tower L’Esplanade Laurier 140 O’Connor Street Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0G5 |

DAVID MURCHISON Consul Consulate General of Canada 1251 Avenue of the Americas New York, N.Y. 10020 |

ROBERT W. MULLEN, JR. Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy LLP 1 Chase Manhattan Plaza New York, N.Y. 10005 |

* The Registrant is

filing this annual report on a voluntary basis.

Table of Contents

The information set forth below is to be

furnished:

| 1. | In respect of each issue of securities of the registrant registered, a brief statement as to: |

| (a) | The general effect of any material modifications, not previously reported, of the rights of the holders of such securities. |

No such modifications.

| (b) | The title and the material provisions of any law, decree or administrative action, not previously reported, by reason of which the security is not being serviced in accordance with the terms hereof. |

No such provisions.

| (c) | The circumstances of any other failure, not previously reported, to pay principal, interest, or any sinking fund or amortization installment. |

No such failure.

| 2. | A statement as of the close of the last fiscal year of the registrant giving the total outstanding of: |

| (a) | Internal funded debt of the registrant. (Total to be stated in the currency of the registrant. If any internal funded debt is payable in a foreign currency, it should not be included under this paragraph (a) but under paragraph (b) of this item). |

Reference is made to pages 25-27 of

Exhibit D.

| (b) | External funded debt of the registrant. (Totals to be stated in the respective currencies in which payable). No statement need be furnished as to inter-governmental debt. |

Reference is made to pages 25-27 of

Exhibit D.

| 3. | A statement giving the title, date of issue, date of maturity, interest rate and amount outstanding, together with the currency or currencies in which payable, of each issue of funded debt of the registrant outstanding as of the close of the last fiscal year of the registrant. |

Reference is made to pages 34-47 of

Exhibit D.

| 4. (a) | As to each issue of securities of the registrant which is registered, there should be furnished a breakdown of the total amount outstanding, as shown in Item 3, into the following: |

| (1) | Total amount held by or for the account of the registrant. |

As at December 1, 2002, the registrant held

a de minimis amount.

| (2) | Total estimated amount held by nationals of the registrant (or if registrant is other than a national government, by the nationals of its national government); this estimate need be furnished only if it is practicable to do so. |

Not practicable to furnish.

| (3) | Total amount otherwise outstanding. |

Not applicable.

| (b) | If a substantial amount is set forth in answer to paragraph (a)(1) above, describe briefly the method employed by the registrant to reacquire such securities. |

Not applicable.

| 5. | A statement as of the close of the last fiscal year of the registrant giving the estimated total of: |

| (a) | Internal floating indebtedness of the registrant. (Total to be stated in the currency of the registrant). |

Reference is made to pages 25-27 of

Exhibit D.

| (b) | External floating indebtedness of the registrant. (Total to be stated in the respective currencies in which payable). |

Reference is made to pages 25-27 of

Exhibit D.

Table of Contents

| 6. | Statements of the receipts, classified by source, and of the expenditures, classified by purpose, of the registrant for each fiscal year of the registrant ended since the close of the latest fiscal year for which such information was previously reported. These statements should be so itemized as to be reasonably informative and should cover both ordinary and extraordinary receipts and expenditures; there should be indicated separately, if practicable, the amount of receipts pledged or otherwise specifically allocated to any issue registered, indicating the issue. |

Reference is made to pages 18-24 of

Exhibit D.

| 7. (a) | If any foreign exchange control, not previously reported, has been established by the registrant (or if the registrant is other than a national government, by its national government), briefly describe such foreign exchange control. |

No foreign exchange controls have been

established by the registrant.

| (b) | If any foreign exchange control previously reported has been discontinued or materially modified, briefly describe the effect of any such action, not previously reported. |

Not applicable.

| 8. | Brief statements as of a date reasonably close to the date of the filing of this report (indicating such date) in respect of the note issue and gold reserves of the central bank of issue of the registrant, and of any further gold stocks held by the registrant. |

Reference is made to page 17 of Exhibit D.

| 9. | Statements of imports and exports of merchandise for each year ended since the close of the latest year for which such information was previously reported. Such statements should be reasonably itemized so far as practicable as to commodities and as to countries. They should be set forth in terms of value and of weight or quantity; if statistics have been established only in terms of value, such will suffice. |

Reference is made to pages 12-14 of

Exhibit D.

| 10. | The balances of international payments of the registrant for each year ended since the close of the latest year for which such information was previously reported. The statements of such balances should conform, if possible, to the nomenclature and form used in the “Statistical Handbook of the League of Nations.” (These statements need be furnished only if the registrant has published balances of International payments.) |

Reference is made to pages 15-16 of

Exhibit D.

On March 12, 1996, Canada established a

program for the offering, from time to time, of its Canada Notes

due nine months or more from date of issue (“Canada

Notes”). During the period from December 1, 2001

through November 30, 2002, Canada did not file with the

United States Securities and Exchange Commission any pricing

supplements relating to the sale of Canada Notes. Consequently,

the portion of Canada Notes sold or to be sold during that

period in the United States or in circumstances where

registration of the Canada Notes is required through

November 30, 2002 was U.S.$0.

Cautionary statement for purposes of the

“safe harbor” provisions of the Private Securities

Litigation Reform Act of 1995.

This annual report, including the exhibits

hereto, contains various forward-looking statements and

information that are based on Canada’s belief as well as

assumptions made by and information currently available to

Canada. When used in this document, the words

“anticipate”, “estimate”,

“project”, “expect”, “should” and

similar expressions are intended to identify forward-looking

statements. Such statements are subject to certain risks,

uncertainties and assumptions. Should one or more of these risks

or uncertainties materialize, or should underlying assumptions

prove incorrect, actual results may vary materially from those

anticipated, estimated or projected. Among the key factors that

have or will have a direct bearing on Canada are the world-wide

economy in general and the actual economic, social and political

conditions in or affecting Canada.

Table of Contents

This annual report comprises:

| (a) | Pages numbered 1 to 5 consecutively. | |

| (b) | The following exhibits: |

Exhibit A:

|

None | |

Exhibit B:

|

None | |

Exhibit C-1:

|

Copy of the 2001 Budget of Canada (incorporated by reference from Exhibit C-4 to Canada’s Amendment No. 3 to Form 18-K for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2000) | |

Exhibit C-2:

|

Copy of the Economic and Fiscal Update October 30, 2002, Department of Finance, Canada (incorporated by reference from Exhibit C-2 to Canada’s Amendment No. 1 to Form 18-K for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2001 on Form 18-K/A dated November 1, 2002) | |

Exhibit D:

|

Current Canada Description | |

Exhibit E:

|

Consent of Deputy Minister of Finance |

This annual report is filed subject to the

instructions for Form 18-K for Foreign Governments and

Political Subdivisions Thereof.

Table of Contents

SIGNATURE

Pursuant to the requirements of the Securities

Exchange Act of 1934, the registrant has duly caused this annual

report to be signed on its behalf by the undersigned, thereunto

duly authorized, at Ottawa, Canada, on the 20th day of December,

2002.

| CANADA | ||||

| By: | /s/ Rob Stewart | |||

| Rob Stewart | ||||

| Senior Chief | ||||

| Financial Markets Division | ||||

| Financial Sector Policy Branch | ||||

| Department of Finance, Canada | ||||

Table of Contents

EXHIBIT INDEX

| Exhibit No. | ||

Exhibit A:

|

None | |

Exhibit B:

|

None | |

Exhibit C-1:

|

Copy of the 2001 Budget of Canada (incorporated by reference from Exhibit C-4 to Canada’s Amendment No. 3 to Form 18-K for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2000) | |

Exhibit C-2:

|

Copy of the Economic and Fiscal Update October 30, 2002, Department of Finance, Canada (incorporated by reference from Exhibit C-2 to Canada’s Amendment No. 1 to Form 18-K for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2001 on Form 18-K/A dated November 1, 2002) | |

Exhibit D:

|

Current Canada Description | |

Exhibit E:

|

Consent of Deputy Minister of Finance |

Table of Contents

Exhibit D

DESCRIPTION OF CANADA

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| Page | ||

General Information

|

3 | |

The Canadian Economy

|

6 | |

External Trade

|

12 | |

Balance of Payments

|

15 | |

Foreign Exchange and International Reserves

|

17 | |

Government Finances

|

18 | |

Debt Record

|

28 | |

Monetary and Banking System

|

29 | |

Tables and Supplementary Information

|

34 |

Unless otherwise indicated, dollar amounts

hereafter in this document are expressed in Canadian dollars.

On December 16, 2002 the noon buying rate in

New York City payable in Canadian dollars (“$”),

as reported by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, was

$1.00 = $0.6399 United States dollars

(“U.S.$”). See “Foreign Exchange and

International Reserves”.

Table of Contents

2

Table of Contents

The information contained herein has been

reviewed by Kevin G. Lynch, Deputy Minister of Finance,

Canada and is included herein on his authority. Certain

information contained in this Exhibit has been extracted or

compiled from public official documents of Canada, which include

statistical data subject to revision. Canada is sometimes

referred to as the “Government of Canada” or the

“Government” in this Exhibit.

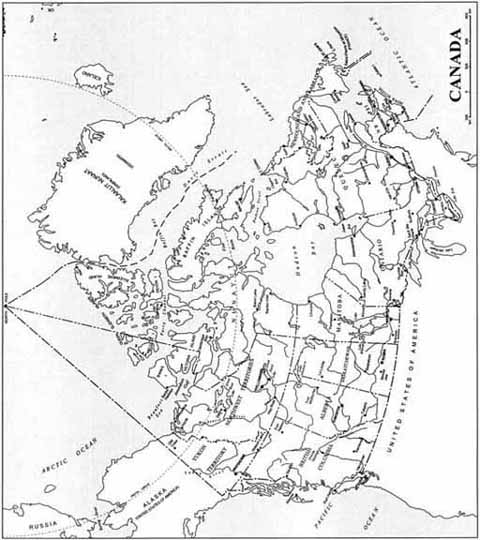

CANADA

GENERAL INFORMATION

Area and Population

Canada is the second largest country in the

world, with an area of 9,984,670 square kilometers of which

about 891,163 square kilometers are covered by fresh water.

The occupied farm land is about 7% and the productive

forest land is about 24% of the total area.

The population on July 1, 2002 was estimated to be

31.4 million. Approximately 64% of Canada’s population

lives in metropolitan areas of which Toronto, Montreal and

Vancouver are the largest. Most of Canada’s population

lives within 325 kilometers of the United States

border.

Form of Government

Canada is a federal state composed of ten

provinces and three territories. In 1867, the United Kingdom

Parliament adopted the British North America Act, which

established the Canadian federation comprised of, at that time,

the Provinces of Ontario, Québec, Nova Scotia and New

Brunswick. Since then, six additional provinces (Manitoba,

British Columbia, Prince Edward Island, Saskatchewan, Alberta

and Newfoundland and Labrador), along with the Yukon Territory,

the Northwest Territories and the new territory of Nunavut

(which was carved out of the Northwest Territories on

April 1, 1999), have become parts of Canada.

The British North America Act (which has

been renamed the Constitution Act, 1867) gave the

Parliament of Canada legislative power in relation to a number

of matters including all matters not assigned exclusively to the

legislatures of the provinces. These powers now include matters

such as defense, the raising of money by any mode or system of

taxation, the regulation of trade and commerce, the public debt,

money and banking, interest, bills of exchange and promissory

notes, navigation and shipping, extra-provincial transportation,

aerial navigation and, with some exceptions, telecommunications.

The provincial legislatures have exclusive jurisdiction in such

areas as education, municipal institutions, property and civil

rights, administration of justice, direct taxation for

provincial purposes and other matters of purely provincial or

local concern.

The executive power of the federal Government is

vested in the Queen, represented by the Governor General, whose

powers are exercised on the advice of the federal Cabinet, which

is responsible to the House of Commons. The legislative branch

at the federal level, Parliament, consists of the Crown, the

Senate and the House of Commons. The Senate has 105 seats.

There are 24 seats each for the Maritime Provinces,

Québec, Ontario and Western Canada, 6 for Newfoundland and

1 each for the three territories. Senators are appointed by the

Governor General on the advice of the federal Cabinet and hold

office until age 75. The House of Commons has

301 members, elected by voters in single-member

constituencies. The leader of the political party that gains the

most seats in each general election is usually invited by the

Governor General to be Prime Minister and to form the

Government. The Prime Minister selects the members of the

federal Cabinet from among the members of the House of Commons

and the Senate (in practice almost entirely from the former).

The House of Commons is elected for a period of five years,

subject to earlier dissolution upon the recommendation of the

Prime Minister or because of the Government’s defeat in the

House of Commons on a vote of no confidence.

The most recent general election was held on

November 27, 2000. As a result of that election the

Liberal Party forms the Government. The distribution of seats in

the House of Commons is as follows: the Liberal Party has

169 seats, the Canadian Alliance Party has 63 seats,

the Bloc Québécois has 35 seats, the

New Democratic Party has 14 seats and the Progressive

Conservative Party has 14 seats. There are

3 independent members and 3 vacant seats.

The executive power in each province is vested in

the Lieutenant Governor, appointed by the Governor General on

the advice of the federal Cabinet. The Lieutenant

Governor’s powers are exercised on the advice of the

provincial cabinet, which is responsible to the legislative

assembly. Each provincial legislature is composed of a

Lieutenant Governor and a legislative assembly made up of

members elected for a period of five years.

The practice of selecting the provincial premier and the

provincial cabinet in each province follows that described for

the federal level, as does dissolution of a legislature.

Table of Contents

The judicial branch of government in Canada is

composed of an integrated set of courts created by federal and

provincial law. At the federal level there are two principal

courts, the Supreme Court of Canada which is the highest appeal

court in Canada and the Federal Court of Canada which, among

other things, deals with federal revenue laws and claims

involving the Government. Judges of the two federally

constituted courts and those of the provincial superior and

county courts are appointed by the Governor General on the

advice of the federal Cabinet and hold office during good

behavior until age 70 or 75. Judges of the magistrates courts

(commonly now known as provincial courts) are appointed by the

provincial government and usually hold office until age 65 or 70.

Constitutional Reform

In April 1982, Her Majesty the Queen proclaimed

the Constitution Act, 1982, terminating British

legislative jurisdiction over Canada’s Constitution. The

Constitution Act, 1982 provides that Canada’s

Constitution may be amended pursuant to an amending formula

contained therein and contains the Canadian Charter of Rights

and Freedoms, including the linguistic rights of Canada’s

two major language groups.

The government of Québec did not sign the

constitutional agreement which led to the repatriation of the

Canadian Constitution and the proclamation of the

Constitution Act, 1982. Although Québec is legally

bound by the Constitution Act, 1982, the government of

Québec set out five conditions for accepting the legal

legitimacy of the Act. Discussions on those principles led on

April 30, 1987 at Meech Lake to a unanimous agreement by

First Ministers on principles respecting each of

Québec’s conditions.

A constitutional resolution to give effect to the

Meech Lake Accord was adopted by Parliament and eight provinces

before the deadline for ratification on June 23, 1990. In

the absence of ratification by Newfoundland and Manitoba, the

amendment was not adopted. In the wake of this event, the most

extensive series of public consultations on constitutional

matters ever to occur in Canada began through the work of both

provincial and federal commissions and committees, among other

things. Recommendations produced by this process were then

assessed by a series of multilateral negotiations involving the

federal, provincial and territorial governments and four

national Aboriginal organizations, held from April to July 1992.

Agreement was reached on a wide range of constitutional issues

through the multilateral process which led to a First

Ministers’ Conference held in Charlottetown in August 1992.

The Charlottetown Accord was an extensive package

of reforms agreed upon by the federal, provincial and

territorial governments and the four Aboriginal organizations.

On October 26, 1992 Canadians were asked in a referendum if

they agreed that the Constitution of Canada should be renewed on

the basis of the Charlottetown agreement. A majority of

Canadians in a majority of the provinces, including a majority

in Québec and a majority of Status Indians living on

reserves, declined to provide such a mandate. Consequently,

governments set aside the constitutional issue and announced

their intention to concentrate on social and economic

initiatives that do not require constitutional change.

Québec

Since September 1994, Québec has been

governed by the Parti Québécois, whose platform calls

for Québec’s accession to independence. On

October 30, 1995, the government of Québec held a

consultative referendum under provincial law, seeking a mandate

to secede from Canada and proclaim Québec’s

independence, after having made a formal offer of a new economic

and political partnership between Québec and the rest of

Canada. The government’s proposal was rejected by a vote of

50.6% against and 49.4% in favour, with a participation rate of

93%. While all sides accepted the 1995 referendum results, the

Parti Québécois has not abandoned the goal of

achieving independence for Québec.

The Government of Canada and the governments of

a number of provinces outside Québec have taken

a series of initiatives since the 1995 referendum aimed at

reinforcing Canadian unity, including non-constitutional

measures (notably on provincial responsibility for labour market

programs), demonstrating openness to Québecers’

aspirations, as well as making efforts to clarify the rules

governing any future referendum and the possible consequences of

a Québec secession.

4

Table of Contents

In September 1996, the Government of Canada

referred a series of legal questions to the Supreme Court

of Canada with a view to clarifying, at both domestic and

international law, whether the government of Québec has the

right to secede from Canada unilaterally. On August 20,

1998, the Supreme Court rendered judgment, ruling that the

government of Québec cannot, under either the Constitution

of Canada or international law, legally effect the unilateral

secession of Québec from Canada. The Supreme Court also

stated that, if a clear majority of Québecers were to

clearly and unambiguously express their will to secede, all

governments in Canada would then have a constitutional

obligation to enter into negotiations to address the potential

act of secession as well as its possible terms should, in fact,

secession proceed.

On June 29, 2000, the Government of Canada

enacted a law to give effect to the requirement for clarity set

out in the opinion of the Supreme Court. That law requires the

House of Commons to assess, prior to any future referendum on

the secession of a province, whether the referendum question

made clear that the province would cease to be part of Canada

and become an independent country. The law further requires

that, after the vote itself, the House of Commons also assess

whether there appeared to be a clear majority in support of

the question. Only if both these conditions were met would the

Government of Canada be authorized to enter into negotiations

which might lead to the constitutional amendments required to

effect secession.

In September 1997, the Premiers of the nine

provinces other than Québec met in Calgary to launch public

consultations on a set of declaratory principles, including

a recognition of the unique character of Québec

society within Canada, which seek to frame the fundamental

values underlying the Canadian federation. Over the winter and

spring of 1998, the legislatures of all nine provinces

participating in the Calgary process passed resolutions of

support for the principles set out in the Calgary declaration.

On November 30, 1998, the Parti

Québecois government was re-elected with a majority of

seats (75 out of 125) in Québec’s National Assembly,

though with a vote count of 42% of the votes cast, slightly

below that received by the main opposition party, the federalist

Liberal Party of Québec, which won 48 seats. A third

party, the Action Démocratique du Québec, which

advocates a moratorium on further referenda on secession, took

12% of the votes cast and won 1 seat.

5

Table of Contents

THE CANADIAN ECONOMY*

General

The following chart shows the distribution of

real gross domestic product (“GDP”) at basic prices

(1997 constant dollars) in 2001, which is indicative of the

structure of the economy.

DISTRIBUTION OF REAL GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT AT

BASIC PRICES(1)

Percentage Distribution in 2001(2)

Source: Statistics Canada, Gross Domestic

Product by Industry.

(1) GDP is a measure of production

originating within the geographic boundaries of Canada,

regardless of whether factors of production are Canadian or

non-resident owned, whereas gross national product

(“GNP”) measures the value of Canada’s total

production of goods and services — that is, the

earnings of all Canadian owned factors of production.

Quantitatively, GDP is obtained from GNP by adding investment

income paid to non-residents and deducting investment income

received from non-residents. GDP at basic prices represents the

value added by each of the factors of production and is

equivalent to GDP at market prices less indirect taxes (net),

plus other production taxes (net). Moreover, these differences

in GDP measures explain any perceived discrepancies in GDP

growth rates in this document.

(2) May not add to 100.0% due to rounding.

(3) The agriculture, forestry, fishing,

hunting, mining and oil and gas extraction sectors include a

service component.

The volume of industry and sector output in the

following discussion provides “constant dollar”

measures of the contribution of each industry to GDP at basic

prices. The share of service-producing industries in real

GDP was 68.7% in 2001 while the remaining 31.3% was attributed

to goods-producing industries.

| * | Annual figures and year-over-year changes are based upon data that are not seasonally adjusted, except where otherwise indicated. Quarterly and semi-annual figures or changes are based upon seasonally adjusted data, except where otherwise indicated. |

6

Table of Contents

The following table shows the composition of

Canada’s real GDP at basic prices (1997 constant

dollars) by sector in 1987 and over the 1997-2001 period.

REAL GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT AT BASIC PRICES BY

INDUSTRY

| For the years ended December 31, | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2001 | 2000 | 1999 | 1998 | 1997 | 1987(2) | 2001 | 1997 | 1987(2) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (millions of 1997 dollars) | (percentage distribution) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Agriculture

|

$ | 14,617 | $ | 15,975 | $ | 16,437 | $ | 15,230 | $ | 14,016 | $ | 12,090 | 1.5 | % | 1.7 | % | 1.8 | % | |||||||||||||||||||

Forestry, fishing and hunting

|

6,593 | 6,905 | 6,675 | 6,466 | 6,411 | 8,149 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 1.2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Mining and oil and gas extraction

|

37,062 | 36,461 | 33,901 | 34,461 | 33,935 | 25,971 | 3.9 | 4.2 | 3.9 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Manufacturing

|

160,935 | 168,825 | 160,150 | 149,390 | 142,282 | 112,727 | 17.0 | 17.4 | 17.1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Construction

|

50,346 | 48,498 | 46,529 | 44,348 | 42,995 | 44,241 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 6.7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Utilities

|

27,288 | 27,960 | 26,705 | 26,140 | 26,685 | 23,010 | 2.9 | 3.3 | 3.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Transportation and warehousing

|

44,531 | 45,265 | 43,306 | 41,036 | 40,337 | 31,112 | 4.7 | 4.9 | 4.7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Wholesale and retail trade

|

107,243 | 104,256 | 98,508 | 92,644 | 85,946 | 69,290 | 11.3 | 10.5 | 10.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Finance, insurance, real estate and leasing

|

186,989 | 180,834 | 174,227 | 166,070 | 161,097 | 116,387 | 19.7 | 19.7 | 17.7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Public administration and defence

|

53,826 | 52,057 | 51,082 | 50,249 | 49,482 | 44,137 | 5.7 | 6.1 | 6.7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Community, business and personal services

|

258,678 | 248,390 | 236,044 | 222,929 | 213,622 | 172,959 | 27.3 | 26.2 | 26.3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TOTAL (1)

|

$ | 948,108 | $ | 935,426 | $ | 893,564 | $ | 848,963 | $ | 816,808 | $ | 658,425 | 100.0 | % | 100.0 | % | 100.0 | % | |||||||||||||||||||

Source: Statistics Canada, Input Output

Division.

(1) May not add to total due to rounding.

(2) Data does not add to total due to rebasing.

The share of service-producing industries in real

GDP at basic prices increased from 65.7% in 1987 to 68.7% in

2001. The fastest growing groups in this sector have been

wholesale and retail trade and finance, insurance, real estate

and leasing which both grew at average annual rates of 3.3% and

3.5%, between 1987 and 2001, compared to an average annual

growth rate of 2.7% for total real GDP (1997 constant dollars).

The goods-producing sector constituted 31.3% of real GDP at

basic prices in 2001, down from 34.2% in 1987. The decline was

most evident in construction with its share declining from 6.7%

to 5.3%, and in utilities, where the share fell from

3.5% to 2.9%.

Real GDP growth was 3.9% in 1998, 5.2% in 1999

and 4.6% in 2000, while manufacturing output growth exceeded

total output growth over this period, increasing by 4.9% in

1998, 7.2% in 1999 and by 4.7% in 2000. Total year-over-year GDP

growth slowed in 2001, increasing by 1.4%, but has rebounded in

2002 to date, increasing by 1.9%, 2.5% and 3.6% in the first,

second and third quarter respectively.

On a year-over-year basis, manufacturing output

contracted by 4.6% in 2001, and by 1.3% in the first quarter of

2002, before rising by 1.2% and 5.0% in the second and third

quarter respectively.

The construction sector was the second largest

goods-producing sector in Canada in 2001. Construction activity

rose by 3.3% in 1998, 4.7% in 1999, 4.2% in 2000 and 3.9%

in 2001. Construction output grew 4.4% year-over-year in

the first quarter of 2002, 4.7% in the second quarter and 5.5%

in the third quarter.

Output from mining and oil and gas extractions

increased at a rate of 1.5% in 1998. Output fell by 0.7% in

1999, rebounded by 7.8% in 2000 and moderated to 1.7%

in 2001. In 2002, year-over-year growth fell by 1.1%

in the first quarter, 2.9% in the second quarter and 0.6% in the

third quarter.

Although the share of agricultural output in

total real GDP in 2001 was 1.5%, agriculture is an important

part of Canada’s economy and a significant contributor to

foreign exchange earnings. Wheat is Canada’s principal

agricultural crop and one of its largest export products by

value. The wheat crop was 24.3 million tonnes in the

1997-98 crop year, 24.1 million tonnes in the 1998-1999

crop year, 26.9 million tonnes in the 1999-2000 crop year

and 26.5 million tonnes in the 2000-2001 crop year. Total

wheat production fell to 20.6 million tonnes in the

2001-2002 crop year. Statistics Canada estimates that the

2002-2003 crop year will be one of the worst growing seasons in

recent history in Western Canada with wheat production estimated

at only 15.5 million tonnes due to exceptionally

dry conditions.

| * | Unless otherwise specified, all growth rates are calculated using real GDP at basic prices, 1997 chained dollars. All percentage changes are compounded at annual rates. For percentage changes over more than one year the method of computation utilizes observations for the first and final years indicated. For percentage changes over less than one year the method of calculation utilizes observations for the period stated and the previous period of the same length. |

7

Table of Contents

Gross Domestic Income and

Expenditure

Real GDP continued to trend upward from 1997 to

2000, growing by 4.2% in 1997, 4.1% in 1998, 5.4% in 1999, and

4.5% in 2000, while nominal GDP grew by 5.5% in 1997, 3.7% in

1998, 7.2% in 1999 and 8.6% in 2000. Real and nominal GDP growth

tapered off in 2001 increasing by 1.5% and 2.6% respectively. In

the first three quarters of 2002, real GDP rebounded by 2.1%,

3.1% and 4.0% respectively (year-over-year); nominal GDP growth

was 0.5%, 3.4% and 6.1% respectively.

GROSS DOMESTIC INCOME AND EXPENDITURE

| First 3 quarters (10) | For the years ending December 31, | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2002 | 2001 | 2001 | 2000 | 1999 | 1998 | 1997 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (in millions of dollars) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

INCOME

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Labor income (1)

|

$ | 590,485 | $ | 567,163 | $ | 568,864 | $ | 545,110 | $ | 502,726 | $ | 475,335 | $ | 453,073 | ||||||||||||||||||

Corporate profits (2)

|

121,197 | 123,876 | 118,227 | 129,821 | 108,745 | 86,132 | 87,932 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Non-farm unincorporated business income

|

71,745 | 66,104 | 66,551 | 63,962 | 61,351 | 57,936 | 54,663 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Farm income

|

1,977 | 2,976 | 2,972 | 1,758 | 1,935 | 1,724 | 1,663 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Other net domestic income (3)

|

58,155 | 65,171 | 63,386 | 62,334 | 53,887 | 53,461 | 54,911 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Net domestic income

|

896,588 | 877,841 | 872,577 | 854,701 | 779,285 | 723,487 | 700,063 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Indirect taxes, capital consumption

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

allowances and residual error

|

235,445 | 217,973 | 219,669 | 210,294 | 201,239 | 191,486 | 182,670 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

GROSS DOMESTIC INCOME

|

$ | 1,132,033 | $ | 1,095,814 | $ | 1,092,246 | $ | 1,064,995 | $ | 980,524 | $ | 914,973 | $ | 882,733 | ||||||||||||||||||

EXPENDITURE

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Consumer expenditure

|

$ | 645,739 | $ | 618,723 | $ | 620,777 | $ | 594,089 | $ | 560,954 | $ | 531,169 | $ | 510,695 | ||||||||||||||||||

Government expenditure

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(goods & services):

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Federal (4)

|

45,864 | 42,599 | 43,168 | 41,599 | 38,160 | 35,250 | 34,011 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Provincial-municipal (5)

|

196,149 | 186,615 | 187,898 | 178,217 | 169,741 | 164,086 | 157,854 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Total government (6)

|

242,013 | 229,213 | 231,066 | 219,816 | 207,901 | 199,336 | 191,865 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

of which current

|

212,763 | 203,111 | 204,492 | 196,004 | 185,317 | 179,317 | 171,756 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

of which capital (7)

|

29,251 | 26,103 | 26,574 | 23,812 | 22,584 | 20,019 | 20,109 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Residential construction

|

61,508 | 51,080 | 52,154 | 48,566 | 45,917 | 42,497 | 43,519 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Business fixed investment:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Non-residential construction

|

51,044 | 52,427 | 52,268 | 50,890 | 46,816 | 45,177 | 43,872 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Machinery and equipment

|

84,405 | 87,277 | 85,504 | 86,693 | 79,977 | 74,116 | 67,346 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Total

|

135,449 | 139,704 | 137,772 | 137,583 | 126,793 | 119,293 | 111,218 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Inventory accumulation:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Business non-farm

|

2,151 | -1,996 | -4,740 | 8,189 | 4,932 | 5,409 | 9,174 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Farm

|

-1,311 | -1,275 | -1,300 | -161 | 55 | -676 | -1,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Total

|

840 | -3,271 | -6,040 | 8,028 | 4,987 | 4,733 | 8,174 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Exports (goods & services) (8)

|

467,080 | 482,611 | 473,000 | 484,331 | 421,796 | 379,203 | 348,604 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Imports (goods & services) (9)

|

-419,417 | -422,591 | -416,498 | -428,934 | -388,157 | -360,871 | -331,271 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Residual error of estimate

|

-1,179 | 345 | 15 | 1,516 | 333 | -387 | -71 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

GROSS DOMESTIC EXPENDITURE

|

$ | 1,132,033 | $ | 1,095,815 | $ | 1,092,246 | $ | 1,064,995 | $ | 980,524 | $ | 914,973 | $ | 882,733 | ||||||||||||||||||

GROSS DOMESTIC EXPENDITURE IN 1997 CHAIN-FISHER

DOLLARS (11)

|

$ | 1,057,402 | $ | 1,025,802 | $ | 1,027,523 | $ | 1,012,335 | $ | 968,451 | $ | 918,910 | $ | 882,733 | ||||||||||||||||||

Source: Statistics Canada, National Income and

Expenditure Accounts.

(1) Includes military pay and allowances.

(2) Includes net interest and

dividends paid to non-residents.

(3) Includes interest, miscellaneous

investment income and government business enterprise profits

before taxes.

(4) Net spending (outlays minus sales)

including gross capital formation and Canada Pension Plan.

(5) Net spending (outlays minus sales)

including gross capital formation and Québec Pension Plan.

(6) Includes government inventories.

(7) Includes inventory accumulations

at all levels of government.

(8) Excludes investment income

received from non-residents.

(9) Excludes investment income paid to

non-residents.

(10) Seasonally adjusted, annual rates.

| (11) | A new formula (Chain-Fisher) is now used to estimate the level of real GDP. This new formula replaces the previous Laspeyres formula. |

8

Table of Contents

Economic Developments*

Nominal GDP at market prices was about

$1.1 trillion in 2001. Real output growth experienced gains

of 4.2% in 1997, 4.1% in 1998, 5.4% in 1999 and 4.5% in 2000,

before slowing to 1.5% in 2001. Year-over-year real GDP growth

rebounded in 2002 to date, registering 2.1% in the first

quarter, 3.1% in the second quarter and 4.0% in the third

quarter.

Real consumer spending rose by 4.6% in 1997, 2.8%

in 1998, 3.9% in 1999, 3.7% in 2000 and 2.6% in 2001.

Year-over-year growth in consumer spending remained robust at

2.1% in the first quarter, 2.7% in the second quarter and 2.9%

in the third quarter of 2002. The personal savings rate declined

steadily between 1991 and 1997, after reaching a peak of 13.8%

in 1991. In 2001, the personal savings rate was 4.6%, increasing

to 5.3% in the first quarter of 2002 and 4.7% in both the second

and third quarter of 2002.

Real non-residential business investment grew at

its highest rate on record in 1997, rising 22.6% before slowing

to 5.3% in 1998. Year-over-year growth in non-residential

business investment was 7.8% in 1999, 8.2% in 2000 and fell by

1.1% in 2001. The strength in non-residential business

investment over this period was largely due to strong increases

in machinery and equipment investment. Year-over-year growth

decreased by 5.2% in the first quarter of 2002, fell by 3.4% in

the second quarter and 4.9% in the third quarter.

Housing starts have generally increased in recent

years. However, the recent levels have tended to be below those

reached in the 1980s. Housing starts rose to 148 thousand

units in 1997, before dropping to 138 thousand units in

1998. Housing starts rebounded in 1999, registering

149 thousand units, and continued rising to

153 thousand units and 163 thousand units in 2000 and

2001 respectively. In the first three quarters of 2002, the

level of housing starts expanded strongly to 204 thousand,

196 thousand and 206 units respectively.

Government spending on current goods and services

contracted between 1994 and 1997 by an average of 0.9% annually.

Growth was 3.2% in 1998, 1.9% in 1999, 2.3% in 2000 and 3.3% in

2001. Year-over-year growth in government spending on goods and

services for 2002 was 2.5% in the first quarter, 2.0% in the

second quarter and 2.2% in the third quarter.

In current dollar terms, the trade balance was

$16.8 billion in 1997 and $17.4 billion in 1998 before

rising rapidly to $33.1 billion in 1999, $54.7 billion

in 2000 and 55.6 billion in 2001. For 2002 the surplus

at annual rates on the foreign trade balance was

$48.4 billion in the first quarter, $45.0 billion in

the second quarter and $47.4 billion in the third quarter.

(See also “Balance of Payments”.)

| * | In this section all figures are reported in real terms unless otherwise noted. |

Table of Contents

Prices and Costs

The year-over-year increase in the GDP implicit

price deflator declined from 1.2% in 1997, to -0.5% in 1998,

rebounding to 1.7% in 1999, 3.9% in 2000 and 1.0% in 2001.

Year-over-year growth in the implicit price deflator fell by

1.6% for the first quarter of 2002, rose to 0.2% in the

second quarter and increased further to 2.0% in the

third quarter.

The year-over-year increase in the consumer price

index (“CPI”) has been moderate since 1996, with

increases of 1.6% in 1997, 0.9% in 1998 and 1.7% in

1999. After remaining below 2.0% during most of the 1990’s,

the year-over-year increase in the CPI registered 2.7% in 2000

and 2.6% in 2001. The increase in 2000 is largely attributable

to a surge in energy prices, while the increase observed in 2001

was more broadly-based. CPI inflation was lower in the first two

quarters of 2002, at 1.5% and 1.3%, respectively, and edged up

to 2.3% in the third quarter.

PRICE DEVELOPMENTS

| G.D.P. | Consumer Price Index | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Implicit | Industrial | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chain | Total | Total Excluding | Product | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| For the years | Price Index | Excluding | Food & | Shelter | Price | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ended December 31, | (1) | Total | Food | Food | Energy | Energy | Services | Index | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (annual percentage changes) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1997

|

1.2 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 1.6 | -0.2 | 0.7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

1998

|

-0.5 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 0.9 | -4.0 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

1999

|

1.7 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 5.7 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

2000

|

3.9 | 2.7 | 1.4 | 3.1 | 16.2 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 4.3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

2001

|

1.0 | 2.6 | 4.5 | 2.1 | 3.3 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 1.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

2001 Q4

|

-1.2 | 1.1 | 3,9 | 0.5 | -8.9 | 1.7 | 2.1 | -1.9 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

2002 Q1

|

-1.6 | 1.5 | 4.1 | 1.0 | -5.4 | 1.9 | 1.7 | -1.1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

2002 Q2

|

0.2 | 1.3 | 2.6 | 1.1 | -8.7 | 2.4 | 1.8 | -1.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

2002 Q3

|

2.0 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.4 | -1.6 | 3.0 | 1.8 | 0.3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Source: Statistics Canada, National Income and

Expenditure Accounts; Consumer Prices and Price Indexes;

Industry Price Indexes.

(1) This implicit price index is based on

seasonally adjusted data.

The average annual increase in new collective

agreements (without cost of living clauses) involving 500 or

more employees for all industries was 3.1% in 2001. Average wage

gains (over the life of the contract) have increased steadily

since 1996. The average settlement was 1.5% in 1997, 1.7% in

1998, 2.2% in 1999 and 2.5% in 2000 and 3.1% in 2001.

Year-over-year, wage gains were 2.9% in the first quarter

of 2002, 2.6% in the second quarter and 2.8% in

the third quarter.

10

Table of Contents

Labor Market

The following table shows labor market

characteristics for the periods indicated.

LABOR MARKET CHARACTERISTICS(1)

(thousands of persons)

| Canada | Atlantic Provinces | Québec | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| For the years | Labor | Employ- | Unemploy- | Labor | Employ- | Unemploy- | Labor | Employ- | Unemploy- | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ended December 31, | Force | ment | ment Rate | Force | ment | ment Rate | Force | ment | ment Rate | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1997

|

15,153 | 13,774 | 9.1 | 1,096 | 944 | 13.9 | 3,606 | 3,195 | 11.4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1998

|

15,418 | 14,140 | 8.3 | 1,115 | 971 | 12.9 | 3,660 | 3,282 | 10.3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1999

|

15,721 | 14,531 | 7.6 | 1,136 | 1,003 | 11.7 | 3,702 | 3,357 | 9.3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2000

|

15,999 | 14,910 | 6.8 | 1,152 | 1,023 | 11.2 | 3,753 | 3,438 | 8.4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2001

|

16,246 | 15,077 | 7.2 | 1,172 | 1,035 | 11.7 | 3,807 | 3,475 | 8.7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2001 Q4

|

16,347 | 15,094 | 7.7 | 1,183 | 1,044 | 11.7 | 3,844 | 3,493 | 9.1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2002 Q1

|

16,490 | 15,199 | 7.8 | 1,190 | 1,047 | 12.1 | 3,884 | 3,530 | 9.1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2002 Q2

|

16,605 | 15,339 | 7.6 | 1,193 | 1,059 | 11.2 | 3,930 | 3,602 | 8.3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2002 Q3

|

16,743 | 15,470 | 7.6 | 1,193 | 1,056 | 11.5 | 3,934 | 3,599 | 8.5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ontario | Prairie Provinces | British Columbia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| For the years | Labor | Employ- | Unemploy- | Labor | Employ- | Unemploy- | Labor | Employ- | Unemploy- | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ended December 31, | Force | ment | ment Rate | Force | ment | ment Rate | Force | ment | ment Rate | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1997

|

5,801 | 5,313 | 8.4 | 2,609 | 2,454 | 6.0 | 2,040 | 1,869 | 8.4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1998

|

5,914 | 5,490 | 7.2 | 2,677 | 2,527 | 5.6 | 2,051 | 1,870 | 8.8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1999

|

6,071 | 5,688 | 6.3 | 2,734 | 2,576 | 5.8 | 2,079 | 1,906 | 8.3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2000

|

6,228 | 5,872 | 5.7 | 2,766 | 2,628 | 5.0 | 2,100 | 1,949 | 7.2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2001

|

6,364 | 5,963 | 6.3 | 2,799 | 2,662 | 4.9 | 2,104 | 1,942 | 7.7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2001 Q4

|

6,399 | 5,965 | 6.8 | 2,814 | 2,674 | 5.0 | 2,107 | 1,918 | 9.0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2002 Q1

|

6,454 | 5,996 | 7.1 | 2,837 | 2,691 | 5.2 | 2,125 | 1,936 | 8.9 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2002 Q2

|

6,479 | 6,025 | 7.0 | 2,857 | 2,699 | 5.5 | 2,147 | 1,954 | 9.0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2002 Q3

|

6,558 | 6,083 | 7.2 | 2,888 | 2,736 | 5.3 | 2,171 | 1,996 | 8.1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Source: Statistics Canada, The Labour

Force.

(1) Unemployment levels are calculated using the

difference between Labour Force and Employment for the quarters.

On a year-over-year basis, employment has

increased steadily since 1993, although more so since 1997.

The labor force has also grown steadily since 1993

(on a year-over-year basis). Employment rose by 0.8% in

1996, while the labor force increased by 1.0% over the same

period. Employment then averaged more than two percent

growth, growing by 2.3%, 2.7%, 2.8% and 2.6% respectively

in 1997 to 2000, before slowing to 1.1% in 2001. Growth in

the labor force was not as strong, registering growth of 1.7%,

1.8%, 2.0%, 1.8%, 1.5% in 1997 through 2001 respectively.

Year-over-year employment growth in 2002 to date was 1.0% in the

first quarter, 1.7% in the second quarter and 2.6% in the third

quarter. Growth in the labor force was 1.9%, 2.3% and 3.1%

respectively over the same period.

After its most recent peak of 11.4% in 1993, the

unemployment rate has generally trended downward through 2000.

The unemployment rate bottomed out at 6.8% in 2000 and rose to

7.2% in 2001. The unemployment rate reached a peak of 7.8% in

the first quarter of 2002, fell to 7.6% in the second quarter

and remained at this level in the third quarter.

11

Table of Contents

EXTERNAL TRADE

Canada has been successful in implementing its

trade goals of freer and more open markets based on

internationally-agreed rules and practices at multilateral,

regional and bilateral levels.

At the multilateral level, Canada continues to be

an active member of the World Trade Organization

(“WTO”) and is fully participating in multilateral

trade negotiations launched in Doha, Qatar in

November 2001. Since the conclusion of the last round of

multilateral trade negotiations in 1995, Canada has taken

a number of actions to liberalize its trade regimes. Canada