https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/18/world/europe/russia-nato.html?action=click&module=RelatedLinks&pgtype=Article

Russia Breaks Diplomatic Ties With NATO

Moscow’s decision to end its diplomatic mission to the alliance will end a long, post-Cold War experiment in building trust between militaries.

MOSCOW — Russia plans to cease its diplomatic engagement with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the Russian foreign minister said on Monday, in the latest sign of unraveling relations between Moscow and the West.

Though significant on a diplomatic level, the announcement was not apparently accompanied by any military moves by Russia threatening European security. And Moscow still maintains diplomatic relations with the individual governments in the alliance.

The decision will end a post-Cold War experiment, never very successful, in building trust between Russia and the Western alliance, established decades ago to contain the Soviet Union, which officials in Moscow accused of later encroaching on former Soviet territory.

By early next month, Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said, Russia will halt the activities of its representative office at NATO headquarters in Brussels and withdraw diplomatic credentials from emissaries of the alliance working in Moscow.

NATO’s response was muted. “We have taken note of the decision by Russia to suspend the work of its diplomatic mission,” a spokeswoman, Oana Lungescu, said. “NATO’s policy toward Russia remains consistent. We have strengthened our deterrence and defense in response to Russia’s aggressive actions, while at the same time we remain open to dialogue.”

The breakoff of diplomatic ties also comes as President Biden is seeking to strengthen the European alliance after former President Donald J. Trump denigrated members as freeloaders on American military spending and threatened to withdraw.

Relations between Moscow and the West have been strained for years, but the immediate impetus for the Russian move was a spy scandal.

Earlier this month, NATO ordered eight Russian diplomats to leave Belgium by Nov. 1, saying they were undeclared intelligence officers. The alliance also reduced the size of the Russian representative office.

In response, Mr. Lavrov said Russia’s entire diplomatic mission would leave by Nov. 1, or a few days after that date.

“Because of NATO’s targeted steps, proper conditions for elemental diplomatic activity don’t exist,” he said. “In response to NATO’s actions, we are halting the work of our permanent representation to NATO, including the work of the main military envoy.”

Relations with the alliance had in any case long ago gone off the rails, he said. NATO had already twice reduced the size of the Russian delegation, in 2015 and 2018, he said. “On the military level there are absolutely no contacts taking place,” he said.

He said NATO had set up a “prohibitive regime” for Russian diplomats in Brussels by banning them from its headquarters building. Without visiting the building, he said, they could not maintain ties with alliance officials.

Mr. Lavrov suggested the expulsions of Russian diplomats had come as an unwelcome surprise, as he had met in New York just days earlier with the alliance’s secretary general, Jens Stoltenberg, and discussed de-escalating tensions.

“He in every way underscored the honest, as he said, interest in the North Atlantic alliance in normalizing relations with the Russian Federation,” Mr. Lavrov said.

NATO could still convey diplomatic messages to Russia’s embassy in Brussels, if necessary, Mr. Lavrov said.

In addition to diplomatic frictions, military tensions have also escalated in recent years, including last spring when Russian troops massed along Ukraine’s border, ostensibly for a military exercise.

In the immediate post-Cold War era, Russia had claimed a moral high ground in relations with NATO. Moscow, Russians noted, had dismantled its alliance of that era, the Warsaw Pact, while NATO in contrast expanded into former Soviet and East Bloc nations. Russia has since initiated new military alliances of its own, with former Soviet states and with China.

Relations were also strained by NATO’s intervention in the Balkan wars in the 1990s against Serbia, a Russian ally.

Russia responded, for a time, by dispatching an outspoken nationalist, Dmitry O. Rogozin, now the director of Russia’s space program, as its emissary to the alliance in Brussels, where he became a thorn in the side of NATO officials.

The problems simmered on. NATO’s view of Russia dimmed further after Russia intervened militarily in Ukraine in 2014. Ukraine is not a NATO member, but Russia’s aggressive moves there revived worries of an expansionist Kremlin agenda in Eastern Europe.

In announcing the halt to Russia’s diplomatic relations with NATO, Mr. Lavrov said Monday that the alliance didn’t show any interest in “equal dialogue or joint work.” He said there was no need to “go on pretending that in the foreseeable future anything will change.”

Monika Pronczuk contributed reporting.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/31/world/europe/biden-putin-russia-united-states.html

Rivals on World Stage, Russia and U.S. Quietly Seek Areas of Accord

There have been a series of beneath-the-surface meetings between the two countries as the Biden administration applies a more sober approach to relations with the Kremlin.

MOSCOW — It might seem as if little has changed for Russia and the United States, two old adversaries seeking to undercut each other around the world.

Russian nuclear-capable missiles have been spotted on the move near Ukraine, and the Kremlin has signaled the possibility of a new intervention there. It has tested hypersonic cruise missiles that skirt American defenses and cut all ties with the American-led NATO alliance. After a summer pause, ransomware attacks emanating from Russian territory have resumed, and this past week, Microsoft revealed a new Russian cybersurveillance campaign.

Since President Biden took office nine months ago, the United States has imposed sweeping new sanctions on Russia, continued to arm and train Ukraine’s military and threatened retaliatory cyberattacks against Russian targets. The American Embassy in Moscow has virtually stopped issuing visas.

As world leaders met at the Group of 20 summit this weekend in Rome, Mr. Biden did not even get the chance to hash things out with his Russian counterpart face to face because President Vladimir V. Putin, citing coronavirus concerns, attended the event remotely.

Yet beneath the surface brinkmanship, the two global rivals are now also doing something else: talking.

The summit between Mr. Biden and Mr. Putin in June in Geneva touched off a series of contacts between the two countries, including three trips to Moscow by senior Biden administration officials since July, and more meetings with Russian officials on neutral ground in Finland and Switzerland.

There is a serious conversation underway on arms control, the deepest in years. The White House’s top adviser for cyber and emerging technologies, Anne Neuberger, has engaged in a series of quiet, virtual meetings with her Kremlin counterpart. Several weeks ago — after an extensive debate inside the American intelligence community over how much to reveal — the United States turned over the names and other details of a few hackers actively launching attacks on America.

Now, one official said, the United States is waiting to see if the information results in arrests, a test of whether Mr. Putin was serious when he said he would facilitate a crackdown on ransomware and other cybercrime.

Officials in both countries say the flurry of talks has so far yielded little of substance but helps to prevent Russian-American tensions from spiraling out of control.

A senior administration official said the United States was “very cleareyed” about Mr. Putin and the Kremlin’s intentions but thinks it can work together on issues like arms control. The official noted that Russia had been closely aligned with the United States on restoring the Iran nuclear deal and, to a lesser degree, dealing with North Korea, but acknowledged that there were many other areas where the Russians “try to throw a wrench into the works.”

Mr. Biden’s measured approach has earned plaudits in Russia’s foreign policy establishment, which views the White House’s increased engagement as a sign that America is newly prepared to make deals.

“Biden understands the importance of a sober approach,” said Fyodor Lukyanov, a prominent Moscow foreign policy analyst who advises the Kremlin. “The most important thing that Biden understands is that he won’t change Russia. Russia is the way it is.”

For the White House, the talks are a way to try to head off geopolitical surprises that could derail Mr. Biden’s priorities — competition with China and a domestic agenda facing myriad challenges. For Mr. Putin, talks with the world’s richest and most powerful nation are a way to showcase Russia’s global influence — and burnish his domestic image as a guarantor of stability.

“What the Russians hate more than anything else is to be disregarded,” said Fiona Hill, who served as the top Russia expert in the National Security Council under President Donald J. Trump, before testifying against him in his first impeachment hearings. “Because they want to be a major player on the stage, and if we’re not paying that much attention to them they are going to find ways of grabbing our attention.”

For the United States, however, the outreach is fraught with risk, exposing the Biden administration to criticism that it is too willing to engage with a Putin-led Russia that continues to undermine American interests and repress dissent.

European officials worry Russia is playing hardball amid the region’s energy crisis, holding out for the approval of a new pipeline before delivering more gas. New footage, circulated on social media on Friday, showed missiles and other Russian weaponry on the move near Ukraine, raising speculation about the possibility of new Russian action against the country.

In the United States, it is the destructive nature of Russia’s cybercampaign that has officials particularly concerned. Microsoft’s disclosure of a new campaign to get into its cloud services and infiltrate thousands of American government, corporation and think tank networks made clear that Russia was ignoring the sanctions Mr. Biden issued after the Solar Winds hack in January.

But it also represented what now looks like a lasting change in Russian tactics, according to Dmitri Alperovitch, the chairman of the research group Silverado Policy Accelerator. He noted that the move to undermine America’s cyberspace infrastructure, rather than just hack into individual corporate or federal targets, was “a tactical direction shift, not a one-off operation.”

Russia has already found ways to use Mr. Biden’s desire for what the White House refers to as a more “stable and predictable” relationship to exact concessions from Washington.

When Victoria Nuland, a top State Department official, sought to visit Moscow for talks at the Kremlin recently, the Russian government did not immediately agree. Seen in Moscow as one of Washington’s most influential Russia hawks, Ms. Nuland was on a blacklist of people barred from entering the country.

But the Russians offered a deal. If Washington approved a visa for a top Russian diplomat who had been unable to enter the United States since 2019, then Ms. Nuland could come to Moscow. The Biden administration took the offer.

Ms. Nuland’s conversations in Moscow were described as wide ranging, but in the flurry of talks between the United States and Russia, there are clearly areas the Kremlin does not want to discuss: Russia’s crackdown on dissent and the treatment of the imprisoned opposition leader Aleksei A. Navalny have gone largely unaddressed, despite the disapproval that Mr. Biden voiced on the matter this year.

While Mr. Biden will not see Mr. Putin in person at the Group of 20 summit in Rome or at the Glasgow climate summit, Dmitri S. Peskov, Mr. Putin’s spokesman, said in October that another meeting this year “in one format or another” between the two presidents was “quite realistic.”

“Biden has been very successful in his signaling toward Russia,” said Kadri Liik, a Russia specialist at the European Council on Foreign Relations in Berlin. “What Russia wants is the great power privilege to break rules. But for that, you need rules to be there. And like it or not the United States is still an important player among the world’s rule setters."

The most notable talks between Russian and American officials have been on what the two call “strategic stability” — a phrase that encompasses traditional arms control and the concerns that new technology, including the use of artificial intelligence to command weapons systems, could lead to accidental war or reduce the decision time for leaders to avoid conflict. Wendy Sherman, the deputy secretary of state, has led a delegation on those issues, and American officials describe them as a “bright spot” in the relationship.

Working groups have been set up, including one that will discuss “novel weapons” like Russia’s Poseidon, an autonomous nuclear torpedo.

While Pentagon officials say that China’s nuclear modernization is their main long-term threat, Russia remains the immediate challenge. “Russia is still the most imminent threat, simply because they have 1,550 deployed nuclear weapons,” Gen. John E. Hyten, who will retire in a few weeks as the vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, told reporters on Thursday

In other contacts, John F. Kerry, Mr. Biden’s climate envoy, spent four days in Moscow in July. And Robert Malley, the special envoy for Iran, held talks in Moscow in September.

Aleksei Overchuk, a Russian deputy prime minister, met with Ms. Sherman and Jake Sullivan, Mr. Biden’s national security adviser — talks that Mr. Overchuk described as “very good and honest” in comments to Russian news media.

Mr. Putin, finely attuned to the subtleties of diplomatic messaging after more than 20 years in power, welcomes such gestures of respect. Analysts noted that he recently also sent his own signal: Asked by an Iranian guest at a conference in October whether Mr. Biden’s withdrawal from Afghanistan heralded the decline of American power, Mr. Putin countered by praising Mr. Biden’s decision and rejecting the notion that the chaotic departure would have a long-term effect on America’s image.

“Time will pass and everything will fall into place, without leading to any cardinal changes,” Mr. Putin said. “The country’s attractiveness doesn’t depend on this, but on its economic and military might.”

Anton Troianovski reported from Moscow, and David E. Sanger from Washington.

https://news.usni.org/2021/07/01/more-nato-ships-enter-black-sea-while-tensions-with-russia-simmer

More NATO Ships Enter Black Sea While Tensions With Russia Simmer

The flagship of Standing NATO Maritime Group 2 entered the Black Sea on Thursday with two more alliance warships set to join the Sea Breeze exercises that started earlier this week, NATO announced.

Frigate ITS Virginio Fasan (F 591) passed through the Bosphorus headed for the Black Sea with a Turkish frigate and will join with a Romanian warship, according to ship spotters in Turkey.

“During [Fasan’s] deployment in the Black Sea, and after the joining of TCG Barbaros and ROS Regina Maria, SNMG2 will participate in bilateral U.S.-Ukraine exercise Sea Breeze,” reads a statement from NATO.

To date, NATO ships that have entered the Black Sea are the U.S. guided-missile destroyers USS Laboon (DDG-58) and USS Ross (DDG-71), French diving support ship FS Alizé A645, British guided-missile destroyer HMS Defender (D63), patrol vessel HMS Trent (P224) and the Dutch frigate HNLMS Evertsen (F805).

The recent ships’ transits into the Black Sea follow last week’s clashes between Russian military forces and Defender and Evertsen. While transiting the Black Sea off the coast of Crimea, Russian fighters and patrol vessels operated close to Defender while Russian forces warned the destroyer away from the vicinity of the coast, USNI News reported at the time.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2kG2R1GY0UI&ab_channel=USNINewsVideo

Earlier this week, images showing Russian fighters with anti-ship missiles flying over Evertsen in

the Black Sea were released by the Dutch defense ministry. Dutch

Defense minister Ank Bijleveld-Schouten called the Russian actions

against Evertsen “irresponsible.”

“Evertsen has every right to sail there,” Bijleveld-Schouten said, according to SkyNews.

“There is no justification whatsoever for this kind of aggressive act,

which also unnecessarily increases the chance of accidents.”

Earlier this week, when asked about the incidents on a television show, Russian president Vladimir Putin said the intent of the alliance ships in the Black Sea was to help establish U.S. bases in the region, according to a translation of the exchange by the BBC.

“They know they cannot win this conflict: we would be fighting for our own territory; we didn’t travel thousands of miles to get to their borders, they did,” he said.

The exercises and the Russian response come after unknown entities have falsified the automatic identification system (AIS) tracks for NATO warships to show them near the Russian-held territory of Crimea.

USNI News reported the automatic identification system (AIS) tracks of Defender and Evertsen were falsified on June 18 to show the warships off of the Russian naval base in Sevastopol in Crimea, while a track for USS Ross (DDG-71) was falsified on June 29 operating about 5 miles from the Crimean coast.

https://www.reuters.com/world/wide-disagreements-low-expectations-biden-putin-meet-2021-06-15/

Far apart at first summit, Biden and Putin agree to steps on cybersecurity, arms control

GENEVA, June 16 (Reuters) - U.S. President Joe Biden and Russian President Vladimir Putin agreed on Wednesday to begin cybersecurity and arms control talks at a summit that highlighted their discord on those issues, human rights and Ukraine.

In their first meeting since he took office in January, Biden asked Putin how he would feel if a ransomware attack hit Russia's oil network, a pointed question making reference to the May shutdown of a pipeline that caused disruptions and panic-buying along the U.S. East Coast.

While Biden stressed that he did not make threats during the three-hour meeting, he said he outlined U.S. interests, including cybersecurity, and made clear to Putin that the United States would respond if Russia infringed on those concerns.

Both men used careful pleasantries to describe their talks in a lakeside Swiss villa, with Putin calling them constructive and without hostility and Biden saying there was no substitute for face-to-face discussions.

They also agreed to send their ambassadors back to each other's capitals. Russia recalled its envoy after Biden said in March that he thought Putin was a "killer." The United States recalled its ambassador soon after.

Putin said on Wednesday that he had been satisfied by Biden’s explanation of the remark.

But there was no hiding their differences on issues such as human rights, where Biden said the consequences for Russia would be "devastating" if jailed Kremlin critic Alexei Navalny died, or cyberspace, where Washington has demanded Moscow crack down on ransomware attacks emanating from Russian soil.

"I looked at him and said: 'How would you feel if ransomware took on the pipelines from your oil fields?' He said: 'It would matter,'" Biden told reporters at an unusual solo news conference, itself an illustration of the tensions between the two nations.

The query referred to a cyberattack that closed the Colonial Pipeline Co (COLPI.UL) system for several days in May, preventing millions of barrels of gasoline, diesel and jet fuel from flowing to the East Coast from the Gulf Coast.

Biden also vowed to take action against any Russian cyberattacks: "I pointed out to him that we have significant cyber capability. And he knows it."

'THIS IS NOT ABOUT TRUST'

Speaking to reporters before Biden, Putin dismissed U.S. concerns about Navalny, Russia's increased military presence near Ukraine's eastern border and U.S. suggestions that Russians were responsible for the cyberattacks on the United States.

He also suggested Washington was in no position to lecture Moscow on rights, batting away question about his crackdown on political rivals by saying he was trying to avoid the "disorder" of a popular movement, such as Black Lives Matter.

"What we saw was disorder, disruption, violations of the law, etc. We feel sympathy for the United States of America, but we don’t want that to happen on our territory and we'll do our utmost in order to not allow it to happen,” he said.

He also seemed to question the legitimacy of arresting the rioters who attacked the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, seeking to stop Biden’s certification as president after he beat his predecessor, Donald Trump, in the November election by over 7 million votes.

U.S. President Joe Biden and Russia's President Vladimir Putin shake hands as they arrive for the U.S.-Russia summit at Villa La Grange in Geneva, Switzerland, June 16, 2021. REUTERS/Kevin Lamarque

Biden said any comparison between what happened on Jan. 6 and the Black Lives Matter movement was “ridiculous.”

U.S.-Russia relations have been deteriorating for years, notably with Russia's 2014 annexation of Crimea from Ukraine, its 2015 intervention in Syria and U.S. charges - denied by Moscow - of meddling in the 2016 election won by Trump.

Neither side gave details on how their planned cybersecurity talks might unfold, although Biden said he told Putin that critical infrastructure should be “off-limits” to cyberattacks, saying that included 16 sectors that he did not publicly identify.

"We need some basic rules of the road that we can all abide by," Biden said he had told Putin.

Biden said he raised human rights issues because it was in the "DNA" of his country to do so, and also because of the fate of U.S. citizens jailed in Russia.

Putin said he believed some compromises could be found, although he gave no indication of any prisoner exchange deal.

Putin, 68, called Biden, 78, a constructive, experienced partner, and said they spoke "the same language." But he added that there had been no friendship, rather a pragmatic dialogue about their two countries' interests.

"President Biden has miscalculated who he is dealing with," said U.S. Republican Senator Lindsey Graham, who is close to Trump. He called it "disturbing" to hear Biden suggest that Putin cared about his standing in the world.

Trump was accused by both Democrats and some Republicans of not being tough enough on Putin, particularly during a jovial 2018 meeting in Helsinki between the two leaders.

This time, there were separate news conferences and no shared meal.

Both Biden and Putin said they shared a responsibility, however, for nuclear stability, and would hold talks on possible changes to their recently extended New START arms limitation treaty.

In February, Russia and the United States extended New START for five years. The treaty caps the number of strategic nuclear warheads they can deploy and limits the land- and submarine-based missiles and bombers to deliver them.

A senior U.S. official told reporters that Biden, Putin, their foreign ministers and interpreters met first for 93 minutes. After a break, the two sides met for 87 minutes in a larger group including their ambassadors.

Putin said it was "hard to say" if relations would improve, but that there was a "glimpse of hope."

“This is not about trust, this is about self-interest and verification of self-interest,” Biden said, but he also cited a “genuine prospect” of improving relations.

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/biden-putin-summit-russia-naval-exercise/

Ahead of Biden-Putin summit, Russia conducts what it calls its largest naval exercise in the Pacific since Cold War

The exercise includes surface ships, anti-submarine aircraft and long range bombers.

U.S. defense officials said that on Sunday, the U.S. scrambled F-22s from Hawaii in response to the bomber flights, but the bombers did not enter the Air Defense Identification Zone and were not intercepted.

At the same time, officials said a U.S. carrier strike group headed by the USS Vinson is operating about 200 miles east of Hawaii, conducting a strike group certification exercise. The exercise had been planned but was moved closer to Hawaii in response to the Russian exercise.

"U.S. Indo-Pacific Command is monitoring the Russian vessels operating in international waters in the Western Pacific," U.S. Indo-Pacific Command spokesman Captain Mike Kafka told CBS News in a statement.

"We operate in accordance with international law of the sea and in the air to ensure that all nations can do the same without fear or contest and in order to secure a free and open Indo-Pacific. As Russia operates within the region, it is expected to do so in accordance with international law."

Earlier this year, Russia built up tens of thousands of troops on the border with Ukraine as a part of what it called an exercise before reducing troops in late April after a month of buildup. The Pentagon called on Russia to be more transparent about troop movements during the buildup.

After meeting with NATO leaders on Monday, Mr. Biden indicated in a press conference that he will address the transparency of Russia's behavior in his meeting with Mr. Putin.

"I shared with our allies that I will convey to President Putin: That I'm not looking for conflict with Russia, but that we will respond if Russia continues its harmful activities and that we will not fail to defend the Transatlantic Alliance or stand up for democratic values," Mr. Biden said.

Putin warns of 'quick and tough' response to any provocation by the West

President Vladimir Putin on Wednesday sternly warned the West against encroaching further on Russia’s security interests, saying Moscow’s response will be “quick and tough” and make the culprits feel bitterly sorry for their action.

The warning during Putin’s annual state-of-the-nation address came amid a massive Russian military buildup near Ukraine, where cease-fire violations in the seven-year conflict between Russia-backed separatists and Ukrainian forces have escalated in recent weeks. The United States and its allies have urged the Kremlin to pull the troops back.

“I hope that no one dares to cross the red line in respect to Russia, and we will determine where it is in each specific case,” Putin said. “Those who organize any provocations threatening our core security interests will regret their deeds more than they regretted anything for a long time.”

Moscow has rejected Ukrainian and Western concerns about the troop buildup, saying it doesn’t threaten anyone and that Russia is free to deploy its forces on its territory. But the Kremlin also has warned Ukraine against trying to use force to retake control of the rebel-held east, saying Russia could be forced to intervene to protect civilians in the region.

“We really don’t want to burn the bridges,” Putin said. “But if some mistake our good intentions for indifference or weakness and intend to burn or even blow up those bridges themselves, Russia’s response will be asymmetrical, quick and tough."

00:31

Outrage over Navanly's treatment

As Putin spoke, a wave of protests started rolling across Russia’s far east in support of imprisoned opposition leader Alexei Navalny. The politician, who is Putin’s most persistent critic and was poisoned with a chemical nerve agent last year, started a hunger strike three weeks ago to protest what he said was inadequate medical treatment and officials’ refusal to allow his doctor to visit him.

Navalny’s treatment and deteriorating condition has caused international outrage and prompted his allies to call the nationwide protests. Police detained several Navalny associates in Moscow and moved to disperse unauthorized demonstrations across Russia, arresting scores.

In his speech, Putin pointed to Russia’s moves to modernize its nuclear arsenal and said the military would continue to build more state-of-the-art hypersonic missiles and other new weapons. He added that the development of the nuclear-armed Poseidon underwater drone and the Burevestnik nuclear-powered cruise missile is continuing successfully.

In an apparent reference to the U.S. and its allies, the Russian leader denounced those who impose “unlawful, politically motivated economic sanctions and crude attempts to enforce its will on others.” He said Russia has shown restraint and often refrained from responding to “openly boorish” actions by others.

The Biden administration last week imposed new sanctions on Russia for interfering in the 2020 U.S. presidential election and for involvement in the SolarWind hack of federal agencies — activities Moscow has denied. The U.S. ordered 10 Russian diplomats expelled, targeted dozens of companies and individuals, and imposed new curbs on Russia’s ability to borrow money.

Russia retaliated by ordering 10 U.S. diplomats to leave, blacklisting eight current and former U.S. officials, and tightening requirements for U.S. Embassy operations.

“Russia has its own interests, which we will defend in line with the international law,” Putin said during Wednesday’s address. “If somebody refuses to understand this obvious thing, is reluctant to conduct a dialogue and chooses a selfish and arrogant tone, Russia will always find a way to defend its position.”

'Bullying Russia' is a 'new sport'

In an emotional outburst, Putin chastised the West for acquiring a defiant stance toward Russia.

“Some countries have developed a nasty habit of bullying Russia for any reason or without any reason at all. It has become a new sport,” he said.

In an apparent reference to the U.S. allies, he compared them to Tabaqui, a cowardly golden jackal kowtowing to Shere Khan, the tiger in Rudyard Kipling’s “Jungle Book.” “They howl to please their lord,” he said.

Russia this week engaged in a tense tug-of-war with the Czech Republic, following Prague’s move to expel 18 Russian diplomats over a massive Czech ammunition depot explosion in 2014. Moscow has dismissed the Czech accusations of its involvement in the blast as absurd and retaliated by expelling 20 Czech diplomats.

Putin also harshly criticized the West for failing to condemn what he described as a botched coup attempt and a failed plot to assassinate Belarus’ President Alexander Lukashenko, allegedly involving a blockade of the country’s capital, power cuts and cyberattacks. Belarusian and Russian security agencies arrested the alleged coup plotters in Moscow earlier this month.

The practice of organizing coups and planning political assassinations of top officials goes over the top and crosses all boundaries,” Putin said, drawing parallels to plots against Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro and the popular protests that led to the ouster of Ukraine’s former Russia-friendly president, Viktor Yanukovych, in 2014.Russia responded to Yanukovych’s ouster by annexing Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula and throwing its support to the separatists in the country’s east. Since then, fighting there has killed more than 14,000 people and devastated the industrial heartland.

Putin dedicated most of his annual address to domestic issues, hailing the nation’s response to the coronavirus pandemic. He said the quick development of three coronavirus vaccines underlined Russia’s technological and industrial potential. He called for a quicker pace of immunizations, voicing hope the country could achieve collective immunity this fall.

He put forward incentives to help the economy recover from the pandemic and promised new social payments focusing on families with children.

(AP)

Russia Bolsters Its Submarine Fleet, and Tensions With U.S. Rise

NAPLES, Italy — Russian attack submarines, the most in two decades, are prowling the coastlines of Scandinavia and Scotland, the Mediterranean Sea and the North Atlantic in what Western military officials say is a significantly increased presence aimed at contesting American and NATO undersea dominance.

Adm. Mark Ferguson, the United States Navy’s top commander in Europe, said last fall that the intensity of Russian submarine patrols had risen by almost 50 percent over the past year, citing public remarks by the Russian Navy chief, Adm. Viktor Chirkov. Analysts say that tempo has not changed since then.

The patrols are the most visible sign of a renewed interest in submarine warfare by President Vladimir V. Putin, whose government has spent billions of dollars for new classes of diesel and nuclear-powered attack submarines that are quieter, better armed and operated by more proficient crews than in the past.

The tensions are part of an expanding rivalry and military buildup, with echoes of the Cold War, between the United States and Russia. Moscow is projecting force not only in the North Atlantic but also in Syria and Ukraine and building up its nuclear arsenal and cyberwarfare capacities in what American military officials say is an attempt to prove its relevance after years of economic decline and retrenchment.

Independent American military analysts see the increased Russian submarine patrols as a legitimate challenge to the United States and NATO. Even short of tensions, there is the possibility of accidents and miscalculations. But whatever the threat, the Pentagon is also using the stepped-up Russian patrols as another argument for bigger budgets for submarines and anti-submarine warfare.

American naval officials say that in the short term, the growing number of Russian submarines, with their ability to shadow Western vessels and European coastlines, will require more ships, planes and subs to monitor them. In the long term, the Defense Department has proposed $8.1 billion over the next five years for “undersea capabilities,” including nine new Virginia-class attack submarines that can carry up to 40 Tomahawk cruise missiles, more than triple the capacity now.

“We’re back to the great powers competition,” Adm. John M. Richardson, the chief of naval operations, said in an interview.

Last week, unarmed Russian warplanes repeatedly buzzed a Navy destroyer in the Baltic Sea and at one point came within 30 feet of the warship, American officials said. Last year some of Russia’s new diesel submarines launched four cruise missiles at targets in Syria.

Mr. Putin’s military modernization program also includes new intercontinental ballistic missiles as well as aircraft, tanks and air defense systems.

To be sure, there is hardly parity between the Russian and American submarine fleets. Russia has about 45 attack submarines — about two dozen are nuclear-powered and 20 are diesel — which are designed to sink other submarines or ships, collect intelligence and conduct patrols. But Western naval analysts say that only about half of those are able to deploy at any given time. Most stay closer to home and maintain an operational tempo far below a Cold War peak.

Credit...Anatoly Maltsev/European Pressphoto Agency

Credit...Anatoly Maltsev/European Pressphoto Agency

The United States has 53 attack submarines, all nuclear-powered, as well as four other nuclear-powered submarines that carry cruise missiles and Special Operations forces. At any given time, roughly a third of America’s attack submarines are at sea, either on patrols or training, with the others undergoing maintenance. American Navy officials and Western analysts say that American attack submarines, which are made for speed, endurance and stealth to deploy far from American shores, remain superior to their Russian counterparts.

The Pentagon is also developing sophisticated technology to monitor encrypted communications from Russian submarines and new kinds of remotely controlled or autonomous vessels. Members of the NATO alliance, including Britain, Germany and Norway, are at the same time buying or considering buying new submarines in response to the Kremlin’s projection of force in the Baltic and Arctic.

But Moscow’s recently revised national security and maritime strategies emphasize the need for Russian maritime forces to project power and to have access to the broader Atlantic Ocean as well as the Arctic.

Russian submarines and spy ships now operate near the vital undersea cables that carry almost all global Internet communications, raising concerns among some American military and intelligence officials that the Russians could attack those lines in times of tension or conflict. Russia is also building an undersea unmanned drone capable of carrying a small, tactical nuclear weapon to use against harbors or coastal areas, American military and intelligence analysts said.

And, like the United States, Russia operates larger nuclear-powered submarines that carry long-range nuclear missiles and spend months at a time hiding in the depths of the ocean. Those submarines, although lethal, do not patrol like the attack submarines do, and do not pose the same degree of concern to American Naval officials.

Credit...Lev Fedoseyev/TASS, via Getty Images

Credit...Lev Fedoseyev/TASS, via Getty Images

Analysts say that Moscow’s continued investment in attack submarines is in contrast to the quality of many of Russia’s land and air forces that frayed in the post-Cold War era.

“In the Russian naval structure, submarines are the crown jewels for naval combat power,” said Magnus Nordenman, director of the Atlantic Council’s trans-Atlantic security initiative in Washington. “The U.S. and NATO haven’t focused on anti-submarine operations lately, and they’ve let that skill deteriorate.”

That has allowed for a rapid Russian resurgence, Western and American officials say, partly in response to what they say is Russia’s fear of being hemmed in.

“I don’t think many people understand the visceral way Russia views NATO and the European Union as an existential threat,” Admiral Ferguson said in an interview.

In Naples, at the headquarters of the United States Navy’s European operations, including the Sixth Fleet, commanders for the first time in decades are having to closely monitor Russian submarine movements through the maritime choke points separating Greenland, Iceland and the United Kingdom, the G.I.U.K. Gap, which during the Cold War were crucial to the defense of Europe.

Credit...Andrew Testa for The New York Times

Credit...Andrew Testa for The New York Times

That stretch of ocean, hundreds of miles wide, represented the line that Soviet naval forces would have had to cross to reach the Atlantic and to stop United States forces heading across the sea to reinforce America’s European allies in time of conflict.

American anti-submarine aircraft were stationed for decades at the Naval Air Station Keflavik in Iceland — in the middle of the gap — but they withdrew in 2006, years after the Cold War. The Navy after that relied on P-3 sub-hunter planes rotating periodically through the base.

Now, the Navy is poised to spend about $20 million to upgrade hangars and support sites at Keflavik to handle its new, more advanced P-8A Poseidon maritime patrol aircraft. That money is part of the Pentagon’s new $3.4 billion European Reassurance Initiative, a quadrupling of funds from last year to deploy heavy weapons, armored vehicles and other equipment to NATO countries in Central and Eastern Europe, to deter Russian aggression.

Navy officials express concern that more Russian submarine patrols will push out beyond the Atlantic into the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. Russia has one Mediterranean port now, in Tartus, Syria, but Navy officials here say Moscow wants to establish others, perhaps in Cyprus, Egypt or even Libya.

“If you have a Russian nuclear attack submarine wandering around the Med, you want to track it,” said Dmitry Gorenburg, a Russian military specialist at the Center for Naval Analyses in Washington.

This month, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency christened a 132-foot prototype drone sea craft packed with sensors, the Sea Hunter, which is made with the intention of hunting autonomously for submarines and mines for up to three months at a time.

The allies are also holding half a dozen anti-submarine exercises this year, including a large drill scheduled later this spring called Dynamic Mongoose in the North Sea. The exercise is to include warships and submarines from Britain, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland and the United States.

“We are not quite back in a Cold War,” said James G. Stavridis, a retired admiral and the former supreme allied commander of NATO, who is now dean of the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University. “But I sure can see one from where we are standing.”

A map on April 21 with the continuation of an article about what Western military officials say is a significantly increased presence of Russian submarines along the coastlines of Scandinavia and Scotland, the Mediterranean Sea and the North Atlantic, meant to contest American and NATO undersea dominance, omitted two countries in NATO. Croatia and Luxembourg are also members.

Follow The New York Times’s politics and Washington coverage on Facebook and Twitter, and sign up for the First Draft politics newsletter.

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-56746138

Russia to consider Biden plan for Putin summit

Image source, Getty Images Image caption, Russia's military has been conducting exercises in Crimea as well as near the border with eastern Ukraine

Image source, Getty Images Image caption, Russia's military has been conducting exercises in Crimea as well as near the border with eastern UkraineHours after US President Joe Biden proposed a summit with Russia's Vladimir Putin, the Kremlin has said it will study the idea.

"It is early to talk about this meeting in terms of specifics," said Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov.

Mr Biden made the proposal on the phone with Mr Putin, raising concerns about Russia's troop build-up on Ukraine's borders, the White House said.

The phone-call late on Tuesday was only the second conversation that President Biden has had with Russia's leader since he took office in January. Moscow recalled its ambassador for consultations last month after Mr Biden said he considered President Putin to be a "killer".

Mr Biden's predecessor, Donald Trump, met Mr Putin in Finland in 2018 and Finnish President Sauli Niinisto has reportedly offered to host a new summit.

Mr Niinisto's office said in a statement that he had a long call with the Russian leader on Tuesday evening and expressed concern about the troop build-up.

Mr Peskov said on Wednesday that "without doubt bilateral ties are important".

How significant is the troop build-up?

The US and European leaders have watched Russian military movements with increasing alarm. Ukraine's presidential spokeswoman, Yulia Mendel, said this week that Russia now had some 40,000 troops on the border with eastern Ukraine and a further 42,000 in Crimea, which was seized and then annexed by Russia in 2014.

Russian-backed separatists then took control of parts of eastern Ukraine in a conflict in which some 14,000 people have died, and clashes have flared up in recent weeks.

Until now Moscow has spoken of its troop movements as an internal affair, and Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu said on Tuesday they were part of a three-week drill to test combat readiness. He accused Nato of moving troops near Russia's borders, which the Western military alliance has denied.

How has Nato responded?

Nato Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg called for an end to the "unjustified, unexplained and deeply concerning" military build-up, after talks in Brussels on Tuesday with US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken as well as Ukraine's foreign minister. Ukraine is not part of Nato but its president, Volodymyr Zelensky, is keen to join.

UK Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab has called on Russia to end "provocations" and de-escalate tensions.

Ukraine's military said it was conducting exercises near the Crimean peninsula in case of a Russian attack and the US is sending two warships to the Black Sea, which has prompted Russia's navy to move some of its fleet there from the Caspian Sea.

In a separate development, the Kremlin said Mr Putin's foreign policy adviser, Yuri Ushakov, had warned the US ambassador over any "unfriendly steps" Washington might take, such as imposing further sanctions.

Readout of President Joseph R. Biden, Jr. Call with President Vladimir Putin of Russia

President Joseph R. Biden, Jr. spoke today with President Vladimir Putin of Russia. They discussed a number of regional and global issues, including the intent of the United States and Russia to pursue a strategic stability dialogue on a range of arms control and emerging security issues, building on the extension of the New START Treaty. President Biden also made clear that the United States will act firmly in defense of its national interests in response to Russia’s actions, such as cyber intrusions and election interference. President Biden emphasized the United States’ unwavering commitment to Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. The President voiced our concerns over the sudden Russian military build-up in occupied Crimea and on Ukraine’s borders, and called on Russia to de-escalate tensions. President Biden reaffirmed his goal of building a stable and predictable relationship with Russia consistent with U.S. interests, and proposed a summit meeting in a third country in the coming months to discuss the full range of issues facing the United States and Russia.

https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/04/02/russia-ukraine-military-biden/

Russia’s Buildup Near Ukraine Puts Team Biden on Edge

Is Russia testing the waters or just testing Biden?

Russia is massing an unusual number of troops on the border with Ukraine, posing an early test for the Biden administration as it looks to repair relations with NATO allies and distinguish itself from former U.S. President Donald Trump’s controversial approach to relations with Moscow.

The buildup of forces on the Ukrainian border, along with hundreds of cease-fire violations in Ukraine’s eastern territories controlled by Russia-backed separatists, has alarmed NATO and sparked a flurry of phone calls between senior members of the Biden administration and their Ukrainian and Russian counterparts.

“They’re probing, they’re trying to see what we’re going to do, what NATO would do, what the Ukrainians would do,” said Jim Townsend, a former U.S. deputy assistant secretary of defense for Europe and NATO until 2017. “Is this a jumpy administration, or is this an administration that’s going to act with resolve? They’re doing all of these things to assess where the new administration is.”

President Joe Biden spoke to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky on Friday, according to a Ukrainian readout, the first conversation between the two countries’ leaders since Trump’s ill-fated call in July 2019 with Zelensky that sparked his first impeachment investigation. “We stand shoulder to shoulder when it comes to preservation of our democracies,” the Ukrainian leader tweeted after the 50-minute conversation.

Envoys from the 30-member NATO alliance met on Thursday to discuss the matter and expressed concern about Russia’s large-scale military exercises and the uptick in cease-fire violations, a NATO official told Foreign Policy. “Russia’s destabilizing actions undermine efforts to de-escalate tensions,” the official said. “NATO continues to support Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. We remain vigilant and continue to monitor the situation closely.”

On Friday, the Kremlin warned that any deployment of NATO troops to Ukraine would escalate tensions further and prompt Russia to take additional measures to protect itself.

The conflict in eastern Ukraine between the country’s armed forces and Russia-backed separatists has periodically flared since a 2015 peace deal brought the worst of the fighting to an end. Observers of the conflict say the current escalation is of a different magnitude than previous scares.

Videos shared by Russian social media users, which are difficult to independently verify, appear to show trains and convoys of military vehicles streaming to the border with Ukraine and Crimea, the strategic Ukrainian peninsula on the Black Sea that Russia illegally annexed in 2014. Observers and experts are still trying to sort out Russian intentions behind the buildup, which appeared to outpace Moscow’s normal tempo for military exercises.

“[Russian President Vladimir Putin is] not so obvious when he pulls the big move. Why is he letting us see this?” said Townsend, the former Pentagon official.

Former U.S. officials saw this as a clear effort by Moscow to test the new Biden administration, which is still parsing policy reviews on how to craft a new strategy toward Russia after other escalations, including a massive hack on U.S. government agencies that Washington has blamed on the Kremlin.

“This could be a troop maneuver where they’re just testing to see how we react, it could be something military, or it could be where he parks people on the border,” a former senior Trump administration official told Foreign Policy. “They need to lay out publicly what the policy is. Further Russian incursions are not acceptable.”

The Crimea annexation in 2014 also started with a major snap military exercise along Russia’s western border with Ukraine, before masked men later poured into the Black Sea territory and overtook it.

Longtime observers of the conflict are skeptical that Russia is planning a renewed invasion of Ukraine, but they did not rule out the possibility entirely. “The thing about Vladimir Putin is that when we are thinking about what he is going to do, we are trying to think that it’s going to be something rational,” said Kirill Mikhailov, a researcher with the Conflict Intelligence Team, which tracks Russian military involvement in Ukraine. “He may have an entirely different view of the world, given that the information that he is getting is presumed to be highly curated.”

The Russian military analyst Pavel Felgenhauer characterized this alternate worldview in comments to the BBC last month: “In the understanding of the Russian military, the West is waging hybrid war against Russia on many fronts: in Belarus, in Ukraine, with respect to Alexey Navalny,” he said.

Robert Lee, an expert on the Russian military and a Ph.D. candidate at King’s College London, said the moves were most likely intended to deter Ukraine from any future offensives in the region. “Russia is showing that they retain escalation dominance,” he said.

Zelensky has made a number of moves against Russian proxies in Ukraine, which some observers said may have factored into Moscow’s calculus. In February, the Ukrainian oligarch Viktor Medvedchuk, a close Putin ally, was sanctioned by Kyiv, and three TV channels controlled by the magnate were shut down.

“It’s not about Medvedchuk as an individual,” said Michael Carpenter, who served as U.S. deputy assistant secretary of defense for Russia, Ukraine, and Eurasia during the Obama administration. “One of the main reasons why the Kremlin keeps these protracted conflicts percolating over time is precisely so that when its other levers of influence, whether they be oligarchs or corrupt politicians among neighboring countries, when they don’t deliver, they always have the option of turning up the heat on the conflict in order to gain influence in that way.”

Former U.S. officials also pointed to Putin’s desire to pressure Germany on multiple fronts, including the controversial construction of the undersea Nord Stream 2 natural gas pipeline that would bypass Ukraine and the Berlin-led Trilateral Contact Group that is tasked with ongoing cease-fire negotiations in eastern Ukraine.

But through Friday, the Ukrainian military continued going through its regular high-readiness training cycles, according to a source familiar with the preparations. Most assessments from the ground indicate that the Russians are conducting strategic posturing, but do not discount a sudden land grab, the source said. Ukraine could also move forward heavy equipment positioned in the west that is aimed at halting a Russian advance, including U.S.-made Javelin anti-tank missiles, which can rapidly be moved to the front lines under rules approved last year.

“The problem with the Russians is everything for them is a red line, and they bluster on everything, and when their position starts to collapse, they’ll backpedal,” a former senior U.S. defense official said. “The Ukrainians understand that better than anyone.”

The buildup comes amid a host of other escalatory activities by Moscow. “They have really brought out a continental-wide saber-rattling event,” said Ben Hodges, who was commanding general of U.S. Army Europe until 2017. Last Friday, the Russian defense ministry published a video of three Russian submarines punching up through ice in the Arctic, a difficult maneuver that Hodges said was a demonstration of capability in a region that has been subject to increasing military competition.

On Monday, NATO reported an “unusual peak” in Russian flights near the fringes of the alliance, with 10 flights being intercepted by NATO planes within a six-hour window. These events, combined with the buildup along the border with Ukraine, are “obviously not a coincidence,” Hodges said.

The tensions come as West-Russia relations have “hit the bottom,” according to Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov. Moscow recalled its ambassador to Washington, Anatoly Antonov, after Biden agreed to a comment that Putin was a “killer” in a recent interview.

But the Biden administration intends to keep its diplomatic channel open to Moscow despite the spike in bilateral tensions. A State Department spokesperson told Foreign Policy that there are “no plans” to recall the U.S. ambassador to Moscow, John Sullivan, to Washington in response to Russia’s decision.

“We remain committed to open channels of communication with the Russian government, both to advance U.S. interests and reduce the risk of miscalculation between our countries,” the spokesperson said.

Even as tensions have increased in the last few days, former U.S. officials said Kyiv remains wary of escalating any conflict, potentially taking the bait from Moscow and allowing Russia-backed forces to further consolidate their gains in the east. Instead, Zelensky is likely to lean on the West, the person said.

“The Ukrainians are better off with a stalemate than escalating and getting their clock cleaned,” the former senior U.S. defense official said. “[Their] best play in the Donbass is international pressure and to wait Putin out. Plinking a few tanks with Javelins isn’t going to do much,” the official said, referring to Ukraine’s U.S.-supplied anti-tank Javelin missiles.

Amy Mackinnon is a national security and intelligence reporter at Foreign Policy. Twitter: @ak_mack

Jack Detsch is Foreign Policy’s Pentagon and national security reporter. Twitter: @JackDetsch

Robbie Gramer is a diplomacy and national security reporter at Foreign Policy. Twitter: @RobbieGramer

https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/hmcs-calgary-china-sea-transit-1.5972098

Canadian warship transits South China Sea as diplomatic tensions remain high

HMCS Calgary passed near the disputed Spratly Islands, claimed by both China and the Philippines

The Department of National Defence says HMCS Calgary passed through the South China Sea while travelling from Brunei to Vietnam on Monday and Tuesday.

The passage did not go unnoticed by China, which shadowed the Canadian ship, according to a Defence official speaking on condition of anonymity.

China claims much of the sea as its territory and has been greatly expanding its military presence in the area. Many of those claims have been rejected by China's neighbours and several international rulings.

The Calgary's passage could aggravate tensions with Beijing, which has been engaged in a diplomatic dispute with Ottawa since Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou was arrested at the Vancouver airport in December 2018.

Beijing subsequently arrested two Canadians, Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor, in what the federal government and others have described as an act of retaliation in response to Meng's detention.

Meng is now facing possible extradition to the U.S. to face fraud allegations, while China has launched court proceedings against Kovrig and Spavor behind closed doors in recent weeks.

Department of National Defence spokesperson Daniel Le Bouthillier confirmed the Calgary passed near the disputed Spratly Islands — which both China and the Philippines claim and where the Chinese military has set up facilities and equipment.

Demonstrating support for allies

He said the South China Sea was the most practical route for the warship. Canadian officials have previously denied trying to send any message when warships have passed through waters claimed by China.

But documents obtained by The Canadian Press last year show such passages are often discussed at the highest levels of government before being approved.

One transit by HMCS Ottawa through the South China Sea's Taiwan Strait last year was described in the documents as having "demonstrated Canadian support for our closest partners and allies, regional security and the rules-based international order."

Defence officials were told to keep quiet about the Ottawa's trip in September 2019, three months after Chinese fighter jets buzzed two other Canadian ships making the same voyage.

https://www.heritage.org/military-strength/assessing-threats-us-vital-interests/russia

Key Topics

About the Index

Resources

Russia

Oct 20, 2021

Alexis Mrachek

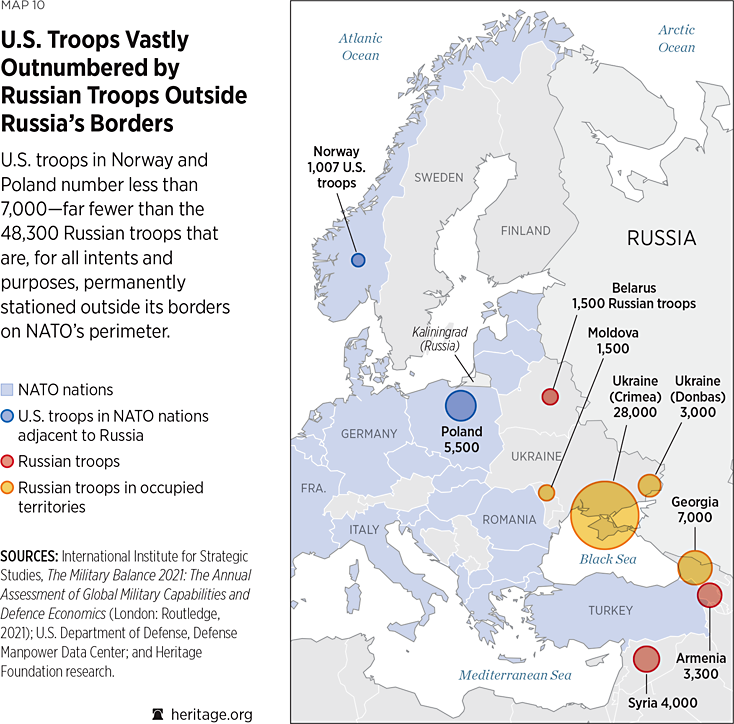

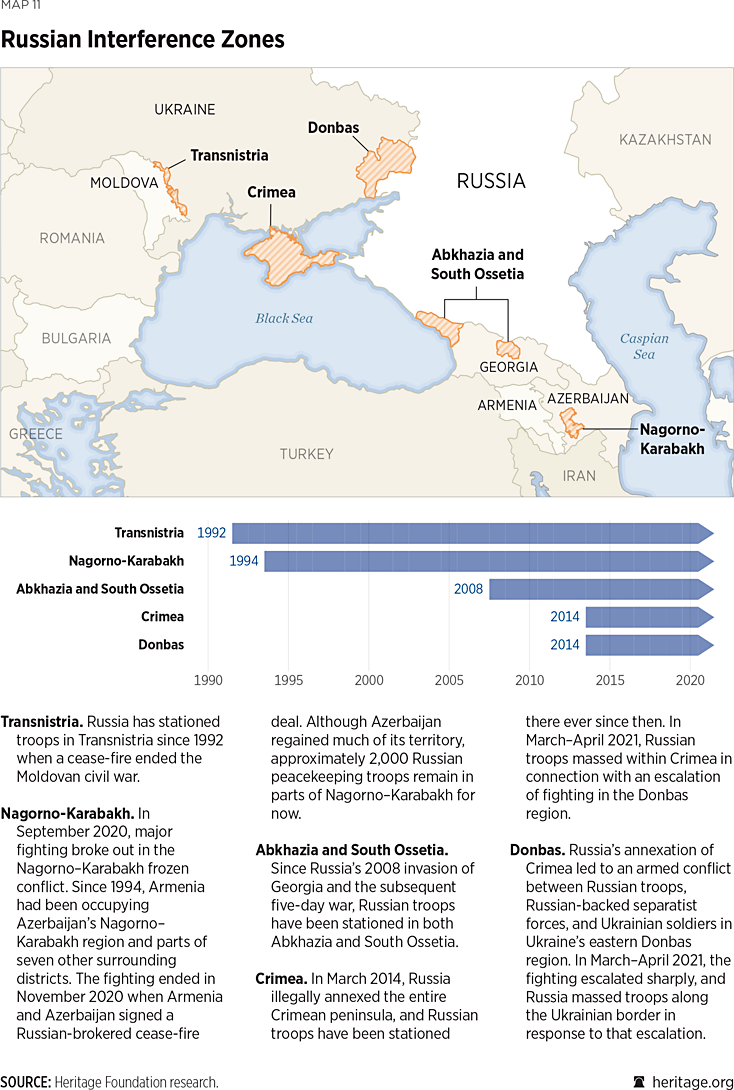

Russia remains a formidable threat to the United States and its interests in Europe. From the Arctic to the Baltics, Ukraine, and the South Caucasus, and increasingly in the Mediterranean, Russia continues to foment instability in Europe. Despite economic problems, Russia continues to prioritize the rebuilding of its military and funding for its military operations abroad. Russia remains antagonistic to the United States both militarily and politically, and its efforts to undermine U.S. institutions and the NATO alliance continue without letup. In Europe, Russia uses its energy position, along with espionage, cyberattacks, and information warfare, to exploit vulnerabilities with the goal of dividing the transatlantic alliance and undermining faith in government and societal institutions.

Overall, Russia possesses significant conventional and nuclear capabilities and remains the principal threat to European security. Its aggressive stance in a number of theaters, including the Balkans, Georgia, Syria, and Ukraine, continues both to encourage destabilization and to threaten U.S. interests.

Military Capabilities. According to the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS):

- Among the key weapons in Russia’s inventory are 336 intercontinental ballistic missiles, 2,840 main battle tanks, 5,220 armored infantry fighting vehicles, more than 6,100 armored personnel carriers, and more than 4,684 pieces of artillery.

- The navy has one aircraft carrier; 49 submarines (including 11 ballistic missile submarines); four cruisers; 11 destroyers; 15 frigates; and 125 patrol and coastal combatants.

- The air force has 1,160 combat-capable aircraft.

- The army has 280,000 soldiers.

- There is a total reserve force of 2,000,000 for all armed forces.1undefinedundefined

In addition, Russian deep-sea research vessels include converted ballistic missile submarines, which hold smaller auxiliary submarines that can operate on the ocean floor.2

To avoid political blowback from military deaths abroad, Russia has increasingly deployed paid private volunteer troops trained at Special Forces bases and often under the command of Russian Special Forces. It has used such volunteers in Libya, Syria, and Ukraine because they help the Kremlin “keep costs low and maintain a degree of deniability,” and “[a]ny personnel losses could be shrouded from unauthorized disclosure.”3

In February 2018, for example, at Deir al-Zour in eastern Syria, 500 pro-Assad forces and Russian mercenaries armed with Russian tanks, artillery, and mortars attacked U.S.-supported Kurdish forces.4

In January 2019, reports surfaced that 400 Russian mercenaries from the Wagner Group were in Venezuela to bolster the regime of Nicolás Maduro.8

During the past few years, as the crisis has metastasized and protests against the Maduro regime have grown, Russia has begun to deploy troops and supplies to bolster Maduro’s security forces.10

In July 2016, Russian President Vladimir Putin signed a law creating a National Guard with a total strength (both civilian and military) of 340,000, controlled directly by him.13

This deal likely directly resulted from the Belarusian protests that broke out in August 2020 following the fraudulent presidential election.

At first, the COVID-19 pandemic severely affected Russia’s economic growth.17

Because of the economic boost following the coronavirus lockdowns, Russia will likely find it easier to fund its military operations.

In 2020, Russia spent $61.7 billion on its military—5.23 percent less than it spent in 2019—but still remained one of the world’s top five nations in terms of defense spending.19

Much of Russia’s military expenditure is directed toward modernization of its armed forces. According to a July 2020 Congressional Research Service report, “Russia has undertaken extensive efforts to modernize and upgrade its armed forces” since its invasion of Georgia in 2008.20

In early 2018, Russia introduced its new State Armament Program 2018–2027, a $306 billion investment in new equipment and force modernization. However, according to the Royal Institute of International Affairs, “as inflation has eroded the value of the rouble since 2011, the new programme is less ambitious than its predecessor in real terms.”23

Russia has prioritized modernization of its nuclear capabilities and “claims to be 81 percent of the way through a modernization program to replace all Soviet-era missiles with newer types by the early 2020s on a less-than one-for-one basis.”24

The armed forces also continue to undergo process modernization, which was begun by Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov in 2008.28

In April 2020, the Kremlin stated that it had begun state trials for its T-14 Armata main battle tank in Syria.30

Russia’s fifth-generation Su-27 fighter fell short of expectations, particularly with regard to stealth capabilities. In May 2018, the government cancelled mass production of the Su-27 because of its high costs and limited capability advantages over upgraded fourth-generation fighters.33

In October 2018, Russia’s sole aircraft carrier, the Admiral Kuznetsov, was severely damaged when a dry dock sank and a crane fell, puncturing the deck and hull.35

Following years of delays, the Admiral Gorshkov stealth guided missile frigate was commissioned in July 2018. The second Admiral Gorshkov–class frigate, the Admiral Kasatonov, began sea trials in April 2019, but according to some analysts, tight budgets and the inability to procure parts from Ukrainian industry (importantly, gas turbine engines) make it difficult for Russia to build the two additional Admiral Gorshkov–class frigates as planned.39

Russia plans to procure eight Lider-class guided missile destroyers for its Northern and Pacific Fleets, but procurement has faced consistent delay.41

In November 2018, Russia sold three Admiral Grigorovich–class frigates to India. It is set to deliver at least two of the frigates to India by 2024.43

Russia’s naval modernization continues to prioritize submarines. In June 2020, the first Project 955A Borei-A ballistic-missile submarine, the Knyaz Vladimir, was delivered to the Russian Northern Fleet, an addition to the three original Project 955 Boreis.46

The Khaski-class submarines are planned fifth-generation stealth nuclear-powered submarines. They are slated to begin construction in 2023 and to be armed with Zircon hypersonic missiles, which have a reported speed of from Mach 5 to Mach 6.50

Russia also continues to upgrade its diesel electric Kilo-class subs.52

Transport remains a nagging problem, and Russia’s defense minister has stressed the paucity of transport vessels. According to a RAND report:

In 1992, just after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Russian Federation military had more than 500 transport aircraft of all types, which were capable of lifting 29,630 metric tons. By 2017, there were just over 100 available transport aircraft in the inventory, capable of lifting 6,240 metric tons, or approximately one-fifth of the 1992 capacity.55undefinedundefined

In 2017, Russia reportedly needed to purchase civilian cargo vessels and use icebreakers to transport troops and equipment to Syria at the beginning of major operations in support of the Assad regime.56

Although budget shortfalls have hampered modernization efforts overall, Russia continues to focus on development of such high-end systems as the S-500 surface-to-air missile system. As of March 2021, the Russian Ministry of Defense was considering the most fitting ways to introduce its new S-500 Prometheus surface-to-air missile system, which is able to detect targets at up to 1,200 miles, with its missile range maxing at approximately 250 miles, “as part of its wider air-defense modernization.” According to one report, the S-500 system will enter full service by 2025.57

Russia’s counterspace and countersatellite capabilities are formidable. A Defense Intelligence Agency report released in February 2019 summarized Russian capabilities:

[O]ver the last two decades, Moscow has been developing a suite of counterspace weapons capabilities, including EW [electronic warfare] to deny, degrade, and disrupt communications and navigation and DEW [directed energy weapons] to deny the use of space-based imagery. Russia is probably also building a ground-based missile capable of destroying satellites in orbit.58undefinedundefined

In December 2020, Russia tested a ballistic, anti-satellite missile built to target imagery and communications satellites in low Earth orbit.59

Military Exercises. Russian military exercises, especially snap exercises, are a source of serious concern because they have masked real military operations in the past. Their purpose is twofold: to project strength and to improve command and control. According to Air Force General Tod D. Wolters, Commander, U.S. European Command (EUCOM):

Russia employs a below-the-threshold of armed conflict strategy via proxies and intermediary forces in an attempt to weaken, divide, and intimidate our Allies and partners using a range of covert, difficult-to-attribute, and malign actions. These actions include information and cyber operations, election meddling, political subversion, economic intimidation, military sales, exercises, and the calculated use of force.61undefinedundefined

Exercises in the Baltic Sea in April 2018, a day after the leaders of the three Baltic nations met with President Donald Trump in Washington, were meant as a message. Russia stated twice in April that it planned to conduct three days of live-fire exercises in Latvia’s Exclusive Economic Zone, forcing a rerouting of commercial aviation as Latvia closed some of its airspace.62

Russia’s snap exercises are conducted with little or no warning and often involve thousands of troops and pieces of equipment.66

Snap exercises have been used for military campaigns as well. According to General Curtis M. Scaparrotti, former EUCOM Commander and NATO Supreme Allied Commander Europe, for example, “the annexation of Crimea took place in connection with a snap exercise by Russia.”69

Russia conducted its VOSTOK (“East”) strategic exercises, held primarily in the Eastern Military District, mainly in August and September of 2018 and purportedly with 300,000 troops, 1,000 aircraft, and 900 tanks taking part.71

One analyst described the extent of the exercise:

[T]he breadth of the exercise was impressive. It uniquely involved several major military districts, as troops from the Central Military District and the Northern Fleet confronted the Eastern Military District and the Pacific Fleet. After establishing communication links and organizing forces, live firing between September 13–17 [sic] included air strikes, air defence operations, ground manoeuvres and raids, sea assault and landings, coastal defence, and electronic warfare.73undefinedundefined

Chinese and Mongolian forces also took part, with China sending 3,200 soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army along with numerous pieces of equipment.74

Threats to the Homeland

Russia is the only state adversary in the Europe region that possesses the capability to threaten the U.S. homeland with both conventional and nonconventional means. Although there is no indication that Russia plans to use its capabilities against the United States absent a broader conflict involving America’s NATO allies, the plausible potential for such a scenario serves to sustain the strategic importance of those capabilities.

Russia’s 2021 National Security Strategy describes NATO as a threat to the national security of the Russian Federation:

Military dangers and military threats to the Russian Federation are intensified by attempts to exert military pressure on Russia, its allies and partners, the buildup of the military infrastructure of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization near Russian borders, the intensification of reconnaissance activities, the development of the use of large military formations and nuclear weapons against the Russian Federation.76undefinedundefined

The same document also clearly states that Russia will use every means at its disposal to achieve its strategic goals:

[P]articular attention is paid to…improving the system of military planning in the Russian Federation, developing and implementing interrelated political, military, military-technical, diplomatic, economic, information and other measures aimed at preventing the use of military force against Russia and protecting its sovereignty and territorial integrity.77undefinedundefined

Strategic Nuclear Threat. Russia possesses the largest arsenal of nuclear weapons (including short-range nuclear weapons) among the nuclear powers. It is one of the few nations with the capability to destroy many targets in the U.S. homeland and in U.S.-allied nations as well as the capability to threaten and prevent free access to the commons by other nations.

Russia has both intercontinental-range and short-range ballistic missiles and a varied arsenal of nuclear weapons that can be delivered by sea, land, and air. It also is investing significant resources in modernizing its arsenal and maintaining the skills of its workforce, and modernization of the nuclear triad will remain a top priority under the new state armament program.78

Russia currently relies on its nuclear arsenal to ensure its invincibility against any enemy, intimidate European powers, and deter counters to its predatory behavior in its “near abroad,” primarily in Ukraine but also concerning the Baltic States.81

This arsenal serves both as a deterrent to large-scale attack and as a protective umbrella under which Russia can modernize its conventional forces at a deliberate pace, but Russia also needs a modern and flexible military to fight local wars such as those against Georgia in 2008 and the ongoing war against Ukraine that began in 2014.

Under Russian military doctrine, the use of nuclear weapons in conventional local and regional wars is seen as de-escalatory because it would cause an enemy to concede defeat. In May 2017, for example, a Russian parliamentarian threatened that nuclear weapons might be used if the U.S. or NATO were to move to retake Crimea or defend eastern Ukraine.82

General Wolters discussed the risks presented by Russia’s possible use of tactical nuclear weapons in his 2020 EUCOM posture statement:

Russia’s vast non-strategic nuclear weapons stockpile and apparent misperception they could gain advantage in crisis or conflict through its use is concerning. Russia continues to engage in disruptive behavior despite widespread international disapproval and continued economic sanctions, and continues to challenge the rules-based international order and violate its obligations under international agreements. The Kremlin employs coercion and aggressive actions amid growing signs of domestic unrest. These actions suggest Russian leadership may feel compelled to take greater risks to maintain power, counter Western influence, and seize opportunities to demonstrate a perception of great power status.83undefinedundefined

Russia has two strategies for nuclear deterrence. The first is based on a threat of massive launch-on-warning and retaliatory strikes to deter a nuclear attack; the second is based on a threat of limited demonstration and “de-escalation” nuclear strikes to deter or terminate a large-scale conventional war.84

Russia’s reliance on nuclear weapons is based partly on their small cost relative to the cost of conventional weapons, especially in terms of their effect, and on Russia’s inability to attract sufficient numbers of high-quality servicemembers. In other words, Russia sees its nuclear weapons as a way to offset the lower quantity and quality of its conventional forces.

Moscow has repeatedly threatened U.S. allies in Europe with nuclear deployments and even preemptive nuclear strikes.85

Russia continues to violate the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, which bans the testing, production, and possession of intermediate-range missiles.87

In December 2018, in response to Russian violations, the U.S. declared Russia to be in material breach of the INF Treaty, a position with which NATO allies were in agreement.90

The sizable Russian nuclear arsenal remains the only threat to the existence of the U.S. homeland emanating from Europe and Eurasia. While the potential for use of this arsenal remains low, the fact that Russia continues to threaten Europe with nuclear attack demonstrates that it will continue to play a central strategic role in shaping both Moscow’s military and political thinking and the level of Russia’s aggressive behavior beyond its borders.

Threat of Regional War

Many U.S. allies regard Russia as a genuine threat. At times, this threat is of a military nature. At other times, it involves less conventional tactics such as cyberattacks, utilization of energy resources, and propaganda. Today, as in Imperial times, Russia uses both the pen and the sword to exert its influence. Organizations like the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) and the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), for example, embody Russia’s attempt to bind regional capitals to Moscow through a series of agreements and treaties.

Russia also uses espionage in ways that are damaging to U.S. interests. For example:

- In May 2016, a Russian spy was sentenced to prison for gathering

intelligence for Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) while

working as a banker in New York. The spy specifically transmitted

intelligence on “potential U.S. sanctions against Russian banks and the

United States’ efforts to develop alternative energy resources.”92undefinedundefined

The European External Action Service, diplomatic service of the European Union (EU), estimates that 200 Russian spies are operating in Brussels, which also is the headquarters of NATO.94

On March 4, 2018, Sergei Skripal, a former Russian GRU colonel who was convicted in 2006 of selling secrets to the United Kingdom and freed in a spy swap between the U.S. and Russia in 2010, and his daughter Yulia were poisoned with Novichok nerve agent by Russian security services in Salisbury, U.K. Hundreds of residents could have been contaminated, including a police officer who was exposed to the nerve agent after responding.96

On March 15, 2018, France, Germany, the U.K., and the U.S. issued a joint statement condemning Russia’s use of the nerve agent: “This use of a military-grade nerve agent, of a type developed by Russia, constitutes the first offensive use of a nerve agent in Europe since the Second World War.”98

Russian intelligence operatives are reportedly mapping U.S. telecommunications infrastructure around the United States, focusing especially on fiber-optic cables.100

- In March 2017, the U.S. charged four people, including two Russian

intelligence officials, with directing hacks of user data involving

Yahoo and Google accounts.101undefinedundefined

Russia has also used its relations with friendly nations—especially Nicaragua—for espionage purposes. In April 2017, Nicaragua began using a Russian-provided satellite station at Managua that, even though the Nicaraguan government denies it is intended for spying, is of concern to the U.S.104