THE LOCKYER FACTOR

by Paul Palango

If you haven’t already noticed, something truly strange happened on the road to finding the truth about what actually happened before, during and after the Nova Scotia massacres of April 18 and 19, 2020.

Lisa Banfield and her $1,200-an-hour lawyer, James Lockyer, appear to have been controlling the show from the very beginning. The Lockyer factor as a not-so-hidden influencer on the news is important to address.

On April 19, 2020, just hours after Lisa Banfield arrived at the door of Leon Joudrey, she contacted lawyer Kevin von Bargen in Toronto to seek advice and help. The lawyer, a friend of Wortman and Banfield, put her onto James Lockyer.

From that moment forward, her every word has been treated as gospel. By the RCMP, by the Mass Casualty Commission, and by the compliant media. Even those who believe her to have been a victim of domestic violence at the hands of Gabriel Wortman (and she clearly was), but also believe she might know more than she’s letting on — and that what she knows might be important to the inquiry’s purported fact-finding mission — have been dismissed as cranks and conspiracists.

According to financial documents released by the inquiry after Lisa Banfield’s dramatic “testimony” on July 15, Banfield reported earnings of $15,288 one recent year.

That would cover a day, plus HST, of Lockyer’s valuable time.

He has been on the clock for 27 months or so, his fees covered by taxpayers through the Mass Casualty Commission.

Banfield’s finances, such as they are, would have been a juicy subject for any curious lawyer, but she wasn’t allowed to be cross examined. Too traumatic, remember.

Questions abound.

Why did Banfield hire an esteemed criminal lawyer? Did no one let her in on her status as a victim?

Lockyer seems like an exotic choice. He made his name from the early ‘90s onward representing men wrongly convicted of murder, such as Stephen Truscott, David Milgaard, Robert Baltovich and Guy Paul Morin. Morin was falsely accused of killing 9-year-old Christine Jessop in Queensville, Ontario, near Toronto.

I was the city editor at the Globe and Mail then. I was intimately involved in the story which was being covered by one of our reporters, Kirk Makin. I even at one point had a meeting with Makin and Morin’s mother, who protested his innocence. At the time I was wrongly unmoved and skeptical of her story, but Makin persisted in digging into it and worked closely with Lockyer. Morin was eventually exonerated. Kudos to all. I hope I got smarter after that.

Lockyer, who lived a block away from me in Toronto, went on to become a champion of the wrongly convicted and started the Innocence Project to work on their behalf. Among his many clients was Rubin (Hurricane) Carter, the former boxer who was wrongly convicted of three murders in Paterson, NJ and was the inspiration for the 1976 Bob Dylan epic Hurricane.

In recent years, Lockyer and his Innocence Project became involved in the case of Nova Scotia’s Glenn Assoun, who was wrongly convicted in 1999 of murdering Brenda Way in Dartmouth four years earlier.

Lockyer worked along with lawyers Sean MacDonald and Phil Campbell to have Assoun’s conviction overturned after he had spent 17 years in prison. In the final years of that campaign an activist reporter named Tim Bousquet took on the Assoun case and wrote about it extensively for years, channeling and publicizing what the lawyers and their investigators had uncovered. To his credit Bousquet uncovered some things on his own.

Perhaps the biggest revelation in the Assoun case was that the RCMP had destroyed evidence and had mislead the courts about Assoun.

Bousquet joined with the CBC in 2020 and produced a radio series, Dead Wrong, about the case. As Canadians should know well by now, both the federal and Nova Scotia governments ignored what the Mounties were caught doing.

Fast forward to the Nova Scotia massacres and the news coverage of it.

As I wrote in my recent book, 22 Murders: Investigating the Massacres, Cover-up and Obstacles to Justice In Nova Scotia, I had a brief fling with Bousquet and his on-line newspaper, The Halifax Examiner, in 2020.

After publishing an opening salvo in Maclean’s magazine in May 2020, I couldn’t find anyone else interested in my reporting, which challenged the official narrative. Maclean’s writer Stephen Maher introduced me to Bousquet. I knew nothing about either him or the Halifax Examiner.

Over the next several weeks, Bousquet published five of my pieces and I was pleasantly surprised to find that the Examiner punched well above its weight. Its stories were being picked up and read across the country. Although I had never met the gruff and the usually difficult-to-reach Bousquet, I thought we had a mutual interest in keeping the story alive as the mainstream media was losing interest in it and were moving on. At first blush, Bousquet seemed like a true, objective journalist determined to find the truth. Hell, I was even prepared to work for nothing, just to get the story out.

“I have to pay you, man,” he insisted in one phone call.

I felt badly taking money from him. I had no idea what his company’s financial situation might be, and I didn’t want to break the bank. He said he could pay me $300 or so per story and asked me to submit an invoice, which I did.

Soon afterward, a cheque for $1500 arrived. I cashed it and then my wife Sharon and I sent him $500 each in after tax money as a donation. Like I said, I didn’t want to be a drag on the Examiner.

Once we made the donations, Bousquet all but ghosted me. He was always too busy to take my calls or field my pitches. I couldn’t tell if I was being cancelled or had been conned.

I began to replay events in my head and the one thing that leapt out to me was Bousquet’s defensive and even dismissive reaction to two threads I thought were important and newsworthy which I wanted to write about.

One was the politically sensitive issue of writing objectively about all the women in the story. There were female victims who had slept with Wortman, which I though was contextually important in understanding the larger story. Bousquet had made it clear that he wasn’t eager for me to write about that. (Be trauma informed!-ed.)

There was also the fact that female police officers were at the intersection of almost every major event that terrible weekend. The commanding officer was Leona (Lee) Bergerman. Chief Superintendent Janis Gray was in charge of the RCMP in Halifax County. Inspector Dustine Rodier ran the communications centre. It was a long list that will continue to grow.

I believe in equal pay for work of equal value but that comes with equal accountability for all. I am gender neutral when evaluating performance.

But it didn’t take psychic powers to detect that gender politics was a big issue with Bousquet – his target market, as it were.

I really wanted to write about Banfield. My preliminary research strongly suggested to me her story was riddled with weakness and inconsistency, but nobody in the mainstream media would tackle it. Hell, for months her name wasn’t even published anywhere outside the pages of Frank magazine.

Bousquet’s position was that Banfield was a victim of domestic violence and that her story, via vague, second-hand and untested RCMP statements, was to be believed. No questions asked.

“You’re going to need something really big to convince me otherwise,” Bousquet said in one of our brief conversations.

Afterward, I did have one face-to-face meeting with him in Halifax. He actually sat in the back seat of our car because Sharon was in the front. We met up because I wanted to tell him about sensitive leads I had which, if pursued, would show that the RCMP had the ability to manipulate its records and destroy evidence in its PROs reporting system.

Considering his involvement in the Assoun case, where that very issue was at the heart of Assoun’s exoneration, I thought Bousquet would be eager to pursue the story.

As I looked at him in the rearview mirror, I could sense his discomfort and lack of interest. So could Sharon who was sitting beside me.

“That was weird,” she said.

Bousquet got out of the car, walked away and disappeared me for good.

It was all so inexplicable. If this was the new journalism that I was experiencing, there was something terribly wrong with it. I couldn’t believe that a journalist like Bousquet who aspired to be a truthteller felt compelled to distill every word or nuance through a political filter first or even something more nefarious.

Later, while writing for Frank Magazine, I broke story after story about the case. Incontrovertible documents showing that the RCMP was destroying evidence in the Wortman case. The Pictou County Public Safety channel recordings showing for the first time what the RCMP was doing on the ground during the early morning hours of April 19. The 911 tapes. The Enfield Big Stop videos. That Lisa Banfield lied in small claims court on two different occasions.

Bousquet either ignored or ridiculed most of those stories in the Halifax Examiner or on his Twitter feed, as if I were making the stories up.

For the most part throughout 2021, the Halifax Examiner didn’t even bother covering the larger story.

Time and time again, “new” stories would be published which were essentially no different from previous ones but all with the same theme: as Ray Davies of the Kinks put it in his masterpiece Sunny Afternoon: “Tales of drunkenness and cruelty.”

The Monster and the Maiden stories, as I called them, reinforced in readers' minds that Banfield was a helpless victim controlled by a demonic Wortman, a narrative that, upon reflection, seemed to perfectly suit Lockyer’s strategy.

For 27 months the RCMP and the Mass Casualty Commission played along, sheltering Banfield as part of their “trauma-informed” mandate, even though there was plenty to be skeptical about her story.

Banfield was beside Wortman for 19 years during which he committed crime after crime. She was reportedly the last person to be with Wortman and her incredible, hoary tale of escape should have been enough to raise suspicions about her.

From the moment she knocked on Leon Joudrey’s door she has been treated as a victim, which to this day astounds law enforcement experts and others who have monitored the case. Many observers, including but not limited to lawyers representing the families of the victims, have serious questions about how Banfield spent the overnight hours of April 18/19. Not helping matters is that she doesn’t appear to have been subjected to any level of normal criminal investigation or evidence gathering. Her clothing wasn’t tested. There were no gunshot residue tests. She wasn’t subjected to a polygraph or any other credible investigative procedure.

Enter James Lockyer of the Innocence Project.

The puppetification of Tim Bousquet

As we moved closer to July 15, the day that Banfield would be “testifying” at the MCC, it is also important to consider what Bousquet and his minions were doing at the Halifax Examiner.

In the weeks and days leading up to Banfield’s appearance, the Examiner’s reporting and Bousquet’s Twitter commentary began to take on an illogical, more contemptuous and even hostile approach to anyone who refused to buy into the RCMP and Banfield’s official version of events.

In a series of hilariously one-sided diatribes, Bousquet lashed out at Banfield’s critics whom he wouldn’t name. Some (likely us) were “bad-faith actors.” He decried the “witchification” of Banfield.

He tweeted: “And just to repeat for the 1000th time: I’ve read transcripts of interviews with dozens of people. I’ve read three years’ of emails between Banfield and GW. I’ve read her Notes app. There is ZERO evidence that she had any prior knowledge (of) GW’s intent to kill people…. The notion that she is ‘complicit’ is pulled out of people’s diarrhetic asses and plain old-fashioned misogyny.”

Oh, misogyny, that old woke slimeball to be hurled at any male who dare be critical of any female.

One can’t help but sense the deft hand of a clever and experienced defence lawyer running up the back of Bousquet’s shirt. That makes sense.

Look at what has transpired on Lockyer’s watch.

Since April 2020, the RCMP and the federal and provincial governments have wrapped themselves in a single, vague and inappropriate platitude – trauma informed.

The original selling point was that this approach would prevent the surviving family members from being further traumatized by the ongoing “investigation” into the massacres.

What actually happened is much more sinister.

Lisa Banfield was coddled and protected the entire time not only by the authorities but also by Lockyer’s friends in the mass media. The wily old fox had the opportunity to mainline his thoughts into the Globe and Mail, the Toronto Star, the CBC, CTV and Global News who unquestioningly lapped it up.

At the MCC, Banfield wasn’t allowed to be cross examined because, as Mr. Lockyer so eloquently explained, cross examination would just lead to more conspiracy theories.

That’s rich.

The search for the truth will only confuse matters -- it’s better for everyone that Banfield spin a much-rehearsed tale without challenge. That’s clearly a $1,200-an-hour lawyer speaking.

The whole world has gone topsy-turvy. The Mass Casualty Commission, the federal and provincial governments, the RCMP and Lisa Banfield are now aligned on one side of the argument.

Meanwhile, the re-traumatized families find themselves agreeing with this magazine and other skeptics and critics.

The final irony is that the Halifax Examiner bills itself as being “independent” and “adversarial.” It seems to be neither these days.

In the end, Tim Bousquet’s approach to covering the Nova Scotia Massacres is, to use his words: “Dead Wrong.”

paulpalango@protonmail.com

Paul Palango is author of the best selling book 22 Murders: Investigating the massacres, cover-up and obstacles to justice in Nova Scotia (Random House).

--

Andrew Douglas

Frank Magazine

phone: (902) 420-1668

fax: (902) 423-0281

cell: (902) 221-0386

andrew@frankmagazine.ca

www.frankmagazine.ca

The Nova Scotia shooting encapsulates all that's wrong with the RCMP

Paul Palango: What happened in Nova Scotia was an example of a cascading failure for the Mounties and there are horrible questions for which answers are needed now

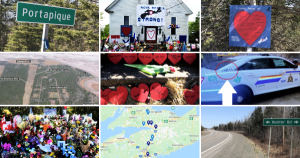

Officers at the scene of the crash between Stevenson’s car and Wortman’s fake RCMP vehicle (John Morris/Reuters)

Paul Palango is the author of three books on the RCMP and a frequent commentator over the past 27 years on RCMP issues

When I awoke that Sunday, my wife, Sharon, was already having a coffee. She told me that she had just seen a Facebook posting that a gunman was on the loose near Truro, N.S.

“Since when?”

“Last night.”

“Any details?

“No. It says the guy may be driving a RCMP vehicle.”

I made myself a coffee and then started scouting around for details. There were hardly any. Scraps of information really. There had been no warning put out to the public. From my experience in dealing with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police over the past 27 years or so, I got that sick feeling that comes from having seen this all before.

“This is bad,” I told her. “Worse than you might think. The RCMP has gone into its shell trying to protect itself and its image. This is probably going to be really bad.”

When the news finally dribbled out, we learned that 22 people were dead, including Mountie Heidi Stevenson. The gunman was also shot dead in a gas station by a Mountie. A messy story resolved. The mourning began for the Mountie … and the others. Tributes went out to the first responders. Flags were ready to be lowered. Funerals, such as they were in this age of COVID-19, were ready to be held.

I talked to a few people and quickly learned some unpublished details. The shooter had tied up his ex-girlfriend or wife to a tree, I was told at the time (though that turned out to be not quite accurate).

There were many dead. When the shooter was taken down at the Irving gas station north of Halifax International Airport, a source told me, the RCMP and Halifax police were in a state of chaos. No one knew who was in charge or what they were supposed to do. “It was a shit show.” One police officer figured out that someone who looked like the shooter was at a gas pump and was acting “hinky.” The shooter knew he had been identified, reached for a weapon and had been shot by the curious and alert officer. Story over, right?

READ MORE: The Nova Scotia shooting and the mistakes the RCMP may have made

In situations like these, I have often been called upon to provide comment—Spiritwood, Mayerthorpe, the Dziekanski death and so on. When three Mounties were murdered in June 2014, I was called by Global TV to comment. I told them I was travelling at the time and couldn’t make it. Actually, I was on my way to Prince Edward Island and was less than 40 minutes away. I had learned from experience that there was no value in trying to point out the shortcomings of the RCMP soon after an event.

“This is not the time for recriminations or criticism,” I had heard more than once.

This time, CBC Radio in Halifax called. I got a little emotional about what had happened. I was extremely critical about the force and asked out loud why Stevenson a 48-year-old mother of two was alone in a car in the situation that got her killed. It had been at least 13 hours since the events had begun in Portapique, spread the next morning to Wentworth and elsewhere.

“Where was the cavalry?” I asked. “Getting gas at Enfield?”

How did it all go so wrong?

Of course, the recriminations began to fly. The mayor of Lunenburg, N.S., contacted me and gave me a dressing down. This was not the time for recriminations, she told me.

But my experience, if it has taught me anything, is the RCMP is adept at pulling at heartstrings during and immediately after an event, like they have over the past two weeks. We are told that there will be a time and place to discuss these issues, but that time never really comes. By then, it’s all old news and time to move on, they will say.

Even now, without all the details in, it has become clear to me that the Nova Scotia massacre encapsulated all that has been and continues to be wrong with the current structure, ethos and performance of the RCMP.

When the RCMP held its first news conference to announce what happened, the two people in charge of the Nova Scotia RCMP, Assistant Commissioner Lee Bergermen and Chief Superintendent Chris Leather looked understandably stressed on one level and like deer caught in the headlights on another. The information coming forth from them was thin and largely unhelpful.

In my CBC interview, I was asked about how long it would take the RCMP to respond to the scene in Portapique on a Saturday night. I said that it took them, based upon what I knew, 30 to 35 minutes.

In its first timeline, the RCMP said it took 12 minutes. The next day it changed the timeline and fudged the response time even more. Finally, it came out with another timeline which said it took 26 minutes. What is the real story?

The RCMP prides itself in being a national police force, but it’s not really a national police force, like say in France. It’s actually a federal police force that rents itself out to the provinces and territories outside Ontario and Quebec. Even then, the only urban areas it polices are Moncton, N.B., and the suburbs of Vancouver—and even there, it’s about to lose its local detachment in Surrey.

The fatal conceit of the Mounties is that every Mountie can do any job, policing is policing. There is no magic.

Here’s how that worked out in the Nova Scotia massacre. Nova Scotia, like other provinces that hire the Mounties to do their provincial or municipal policing, have no say who the RCMP puts in charge or hires in the province.

Bergerman, the officer in charge, spent almost her entire career in federal policing in British Columbia and Ontario. She didn’t do much on the ground in-your-face policing.

However, working on organized crime and counter terrorism is akin to the difference between cricket and baseball. Both have bats and balls, but they are fundamentally different games.

Leather, who started out as a street cop in a regional force outside Toronto, joined the Mounties and became what is known in the force as a “carpet cop.” He moved his way up through federal policing and the corridors of power in Ottawa to be appointed last November as head of operations in Nova Scotia. He was in charge of the police on the ground.

At the second RCMP news conference, the force trotted out the number three in the province, Superintendent Darren Campbell, who was in charge of support services. He’s the guy who makes sure everyone has what they need, especially in an emergency like this one. Where did he come from? As a Staff-Sergeant, he was at RCMP Corps, protecting the legacy and traditions of the RCMP, before he was promoted to Inspector as an assistant in Ottawa to an assistant commissioner. Another former carpet cop.

Instead of tackling the issue head on, they planned and planned, so that no one could be accused of breaching “best practice” protocols.

“This incident was dynamic and fluid,” said Leather in a statement on April 22. “The RCMP have highly trained and capable Critical Incident Command staff who were on site in Portapique. Operational Communications Centre operators assisting the response and police presence was significant. The members who responded used their training and made tough decisions while encountering the unimaginable.”

But as they planned, they failed to put out proper alerts, failed to draw on other forces for help, like Truro and Amherst, failed to set up a secondary perimeter and failed to shut down the very few roads in Central Nova Scotia where the killer was wandering on his deadly mission.

For the RCMP this was an example of a cascading failure that began on Portapiqaue Beach Road—there are suggestions that the Mounties may have been slow to respond there—to the ultimate climax with the accidental meeting between the police and the gunmen at the gas pumps. From the outset the Mounties appear to have become fixated on their own manpower problems and poor decisions at the original crime scene. They then evolved into magical thinking—the gunmen probably killed himself because that’s what a lot of these guys do.

Finally, there is the sad case of Constable Stevenson. She joined the Mounties and was sent to the Musical Ride, even though she hadn’t ever ridden a horse. She spent 13 years there. When she came back to Nova Scotia, she was a press liaison. She was a community support officer, like those who go into schools. She was a traffic cop in Enfield and she was a 48-year-old mother of two.

Yes, she died a hero, but did she have to die? How did she die? Was she sent to her death by incompetent overseers? The Mountie union says she crashed her car into the killer’s fake police car or was it the other way around? Look at the photos. The only car equipped to survive such a crash was the one driven by the bad guy. His vehicle was fitted with a push bar or ram package, as it’s called. The RCMP has resisted for years improving the safety of his vehicles after it became an issue in Spiritwood, Sask., in 2006. Back then two Mounties rammed a vehicle not equipped with a push bar. Their airbags went off and like sitting ducks they were each shot in the head by the person they were trying to apprehend. Did that happen to Stevenson, too?

Why was she alone there, 13 hours after the rampage had begun? Why were the heavily armed specialists still gassing up almost half an hour after she and another Mountie had been shot in Shubenacadie 20 minutes away? And the Mounties only got their man after one alert officer’s instincts—his Spidey sense—told him something wasn’t right about the guy sitting in a Mazda at a gas pump.

There are a thousand horrible questions for which answers are needed.

But Nova Scotians and Canadians must get over suspending their disbelief and their fond memories of the Musical Ride to do the hard work of addressing this very important issue.

The time has come for recriminations.

MORE ABOUT NOVA SCOTIA:

The Nova Scotia killer had ties to criminals and withdrew a huge sum of cash before the shooting

New evidence including a video of the killer raises questions about his activities prior to the Portapique shooting and RCMP transparency around the case

A still from a video showing Gabriel Wortman in the Brinks office on March 30, 2020.

The man who murdered 22 people in a two-day shooting rampage in Nova Scotia in late April withdrew $475,000 in cash 19 days before he donned an RCMP uniform and started gunning down his neighbours, contacts and random strangers.

Gabriel Wortman withdrew the money from the Brink’s office at 19 Ilsley Ave. in Dartmouth, N.S., on March 30, according to a source close to the police investigation, who provided Maclean’s with two videos.

The first video shows Wortman driving what appears to be one of his decommissioned white police cruisers into the fenced yard of the security facility. He is wearing a baseball cap and leather jacket. In the second video, taken inside, he conducts a transaction, then walks back to his cruiser with a carryall apparently filled with 100-dollar bills, according to the source, and stashes the bag in the trunk of his vehicle.

A uniformed Brink’s employee at the Dartmouth location said recently: “People are always surprised by how much money like that takes up so little space.”

That amount of hundreds would weigh less than five kilograms.

Wortman, a 51-year-old denturist, is said to have arranged the withdrawal from Brink’s after transferring the cash from an account at a major Canadian bank.

In Wortman’s last will and testament, a handwritten document he wrote in 2011, which was published last week, Wortman declared a number of properties assessed for about $700,000. The true real estate market value would likely be higher. He also declared about $500,000 in personal property, RRSPs and insurance policies.

The withdrawal of $475,000 suggests Wortman may have converted all of his liquid assets into cash or that he had a hidden stash of cash.

It is not clear what happened to the money from the moment the killer took it out of the Brink’s location to the time he was shot by RCMP officers during an attempted arrest at a gas station in Enfield, N.S., on April 19.

The lawyer for family members of the killer’s victims said Wednesday that the estate filing at probate court lists a large sum of cash, which he believes was recovered by the RCMP.

“I assume the public trustee has it,” said Robert Pineo, who is suing the estate.

Wortman’s common-law spouse filed a court document May 25 renouncing any claim on the estate, heading off a legal dispute with relatives of the victims.

“The goal is to liquidate his entire estate and have it made available to the family members,” he said.

On Tuesday, Pineo filed a proposed class-action lawsuit against the RCMP and the province, alleging that the force failed to “protect the safety and security of the public.”

Nova Scotia RCMP did not respond to questions on Wednesday about what became of the money or whether Wortman was connected to any organized crime investigations.

A still from a video showing Gabriel Wortman in the Brink’s yard on March 30, 2020.

The officer who swore the RCMP’s first search warrants was Sgt. Angela Hawryluk. A 28-year veteran of the RCMP, Hawryluk stipulated in the documents that she is experienced in outlaw biker gangs, drug trafficking and confidential informants.

Superintendent Darren Campbell seemed to rule out the possibility that Wortman was a confidential informant for the RCMP at a press briefing on June 4. “The gunman was never associated to the RCMP as a volunteer or auxiliary police officer, nor did the RCMP ever have any special relationship with the gunman of any kind,” he said.

However, according to one law-enforcement source, Wortman often spent time with Hells Angels, and he had at least one associate with links to organized crime.

Sources say he was friendly with Peter Alan Griffon, a Portapique neighbour linked to a Mexican drug cartel. Sources say Griffon printed the decals that Wortman used on the replica RCMP cruiser he used in his murders.

In 2014, Griffon, then 34, was arrested by Edmonton police as part of an operation against a drug trafficking ring operated by the Mexican cartel La Familia and elements of the ruthless multi-national El Salvadoran gang MS-13. He pled guilty and was sentenced to seven years in prison on Dec. 12, 2017, for possession of a controlled substance for the purpose of trafficking and weapons charges.

At the time of the arrest police said they had seized from Griffon’s home: four kilograms of cocaine, ecstasy, $30,000 in cash, two .22 calibre rifles, one with a silencer, a .44 calibre Desert Eagle handgun, a sawed-off shotgun, thousands of bullets and body armour.

Police issued a second warrant for Griffon’s arrest in 2015 after he returned to Nova Scotia, in violation of his bail conditions. He is believed to have been living in Portapique with his parents since 2019.

Sources say Griffon, who was friendly with Wortman, was working at a print shop and that he printed the decals without the permission of the business owner. Another law enforcement source says Wortman and Griffon were part of a group of drinking buddies in the Portapique area.

Griffon is no longer working at the print shop. RCMP said in May that the business owner and the person who printed the decals have co-operated with their investigation.

Griffon did not respond to Facebook messages and calls seeking comment on his relationship with Wortman.

Griffon is the second cousin of one of the victims, Sean McLeod, who was murdered along with his partner, Alanna Jenkins, on the morning of April 19 in West Wentworth, N.S.

According to obituaries, Griffon and McLeod’s mothers are sisters.

McLeod was a corrections officer at the Springhill Institution, a federal medium-security prison, while Jenkins worked in a federal corrections institute for women in Truro.

It is not known if Griffon was imprisoned at Springhill.

McLeod and Jenkins were the first two victims of a total of nine in the second day of Wortman’s rampage. The night before he had killed 13 people in Portapique and gave the RCMP the slip, escaping on a dirt road in his replica cruiser while much of the small seaside community was in flames.

Wortman appears to have spent several hours at the home of McLeod and Jenkins. He murdered the couple, set their home on fire and then murdered neighbour Tom Bagley, a volunteer firefighter who is believed to have approached the property to investigate the fire.

Family members of victims and law-enforcement officials have raised questions about the RCMP’s handling of the event. The force failed to contain Wortman, did not block the highway links to Truro and Halifax and did not issue a provincial alert. Two officers also shot up the firehall in Onslow.

A former neighbour of Wortman has expressed frustration that the RCMP did not act earlier. Brenda Forbes, a veteran of the Canadian Armed Forces, told the RCMP in 2013 that he had a stash of illegal weapons, and that she had heard three male witnesses had seen Wortman strangling and hitting his common-law wife. Forbes said the RCMP abandoned their investigation because witnesses were unwilling to come forward. The RCMP have said that privacy law prevents them from commenting on complaints that do not result in charges.

An RCMP officer, speaking off the record because the officer is not authorized to discuss the case, said this week that the RCMP’s inaction on the complaint from Forbes seems odd.

“There’s zero tolerance, if we get called in to a domestic, somebody’s got to go, if there’s enough evidence,” the officer said. “It’s a simple 487, a search warrant to go get those guns. I would have wrote it off the statement from the two military people.”

Forbes’ complaint was not Wortman’s first run-in with police. Two years earlier, a source told a Truro police officer that Wortman was armed and wanted to kill a police officer. This information was sent to police agencies throughout Nova Scotia as a bulletin, but RCMP have not provided information on how they acted on it.

Wortman’s father told Frank magazine that he told police about 10 years ago that he had heard his son was threatening to kill him, but that after his son denied the threat and the existence of firearms to police, police did not investigate further. Years before that, he says, while on vacation in Cuba, without warning Wortman had repeatedly punched him in the head until he was unconscious. And in 2002, Wortman pleaded guilty to assaulting a 15-year old boy, but received a conditional discharge if he completed nine months probation and paid a $50 fine. The boy, now grown, has told Global news reporters that he wishes more had been done.

A number of current and former RCMP members familiar with the way the force handles undercover operations but not privy to details about this investigation have speculated that Wortman’s case has the hallmarks of a police informant operation.

Officers are struck by a speeding ticket the RCMP issued Wortman at 5:58 pm on Feb. 12, 2020, on Portapique Beach Road. Wortman was driving one of the former police vehicles in his collection.

At the time the ticket was issued, the RCMP was in the midst of undertaking multiple arrests of Hell’s Angels and their associates in Halifax and New Brunswick. Officers speculate that if Wortman was a confidential informant that his cover had been blown.

“The ticket stinks” said one current RCMP member. “At 6 o’clock at night in February in rural Nova Scotia nobody is doing radar. But it’s a standard trick used to pass messages to informants or create cover to prove to the targets that the informant and the police are on opposite teams.”

To date, both the federal and provincial governments have deflected calls for a public inquiry into the worst mass shooting in Canadian history.

Last week, Nova Scotia Attorney General Mark Furey indicated that a joint federal-provincial inquiry would be announced, but that has not happened. Furey, a former RCMP Staff-Sergeant, has said in the past that he believes he can be objective in dealing with the force and does not have a conflict of interest.

A number of current and former police officers have told Maclean’s that they are suspicious about the motives behind the delay in calling an inquiry.

A current RCMP member who is aware of the inner operations of the RCMP said the real story about the lead-up to the shootings and what actually happened on the weekend of April 18 and 19 would likely be contained in internal documents within the force. The RCMP member pointed specifically to a digital document called a Form 2315. In those forms the RCMP in any province would typically describe in candid language the status of any ongoing major investigation or project. The information in these forms is emailed to a working group, likely under the Deputy Commissioner in charge of Operations, and then on to the Commissioner.

“In those forms the RCMP will speak freely about what happened,” the Mountie said in one of several interviews. “You have to get your hands on them. That’s where the real story can be found.”

The unwillingness of the RCMP and governments to provide a more detailed account of what happened has frustrated and angered some family members of the deceased.

On May 31, Darcy Dobson, whose mother, Heather O’Brien, was murdered by Wortman on April 19, expressed anger in a Facebook post: “If this is the worst massacre in Canadian history why are we not trying to learn from it? What’s the hold up in the inquiry? Why hasn’t this happened yet? Where are we in the investigation? Was someone else involved? Why can’t we get any answers at all 40 days in?! The fact that anyone of us has to ask these questions is all very concerning and only makes everyone feel inadequate, unimportant and unsafe.”

RCMP say they are still investigating where Wortman got the four illegal guns he used in his rampage, declining to release details because of the ongoing investigation.

An RCMP officer not authorized to comment said investigators appear to be trying to avoid public scrutiny.

“They’re closing shit off as fast as they can. They don’t want to open up everything else.”

CORRECTION, JUNE 17, 2020: An earlier version of this story misidentified where Alanna Jenkins worked. It was a federal corrections institute for women, not a provincial one.

CORRECTION, JUNE 18, 2020: Peter Griffon is the second cousin of one of the victims, Sean McLeod, not a first cousin as stated in an earlier version of this story.

Contact our reporters:

Stephen Maher: stephenjamesmaher@gmail.com

Shannon Gormley: shannon.n.gormley@gmail.com

Paul Palango: paulpalango@eastlink.ca

The Nova Scotia shooter case has hallmarks of an undercover operation

Police sources say the killer's withdrawal of $475,000 was highly irregular, and how an RCMP ‘agent’ would get money

A still from a video showing Gabriel Wortman in the Brink's yard on March 30, 2020.

This story was last updated on June 23, 2020

The withdrawal of $475,000 in cash by the man who killed 22 Nova Scotians in April matches the method the RCMP uses to send money to confidential informants and agents, sources say.

Gabriel Wortman, who is responsible for the largest mass killing in Canadian history, withdrew the money from a Brink’s depot in Dartmouth, N.S., on March 30, stashing a carryall filled with hundred-dollar bills in the trunk of his car.

According to a source close to the police investigation the money came from CIBC Intria, a subsidiary of the chartered bank that handles currency transactions.

Sources in both banking and the RCMP say the transaction is consistent with how the RCMP funnels money to its confidential informants and agents, and is not an option available to private banking customers.

The RCMP has repeatedly said that it had no “special relationship” with Wortman. RCMP Supt. Darren Campbell reiterated that statement during an interview with the Toronto Star published online, and in its print newspaper on Sunday, saying: “The gunman had no special relationship with the RCMP whatsoever.” Campbell told the Star: “The investigation has not uncovered any relationship between the gunman and the RCMP outside of an estranged familial relationship and two retired RCMP members.”

According to the Star story: “Campbell said the reason for Wortman’s large cash withdrawal, which he confirmed was hundreds of thousands of dollars, was not fully known, ‘however, there are indications that near the time of the withdrawal the gunman believed that due to the worldwide pandemic, that his financial assets were safer under his control.'”

Campbell declined to be interviewed by Maclean’s on Friday, prior to this story’s publication online, and again on Tuesday.

Court documents show Wortman owned a New Brunswick-registered company called Berkshire-Broman, the legal owner of two of his vehicles (including one of his police replica cars). Whatever the purpose of that company, there is no public evidence that it would have been able to move large quantities of cash. Wortman also ran his own denturist business and there is no reason to believe it also would require him to handle large amounts of cash.

If Wortman was an RCMP informant or agent, it could explain why the force appeared not to take action on complaints about his illegal guns and his assault on his common-law wife.

READ MORE: The Nova Scotia killer had ties to criminals and withdrew a huge sum of cash before the shooting

A Mountie familiar with the techniques used by the force in undercover operations, but not with the details of the investigation into the shooting, says Wortman could not have collected his own money from Brink’s as a private citizen.

“There’s no way a civilian can just make an arrangement like that,” he said in an interview.

He added that Wortman’s transaction is consistent with the Mountie’s experience in how the RCMP pays its assets. “I’ve worked a number of CI cases over the years and that’s how things go. All the payments are made in cash. To me that transaction alone proves he has a secret relationship with the force.”

A second Mountie, who does not know the first one but who has also been involved in CI operations, also believes that Wortman’s ability to withdraw a large sum of money from Brink’s is an indication that Wortman had a link with the police. “That’s tradecraft,” the Mountie said, explaining that by going through CIBC Intria, the RCMP could avoid typical banking scrutiny, as there are no holds placed on the money.

“That’s what we do when we need flash money for a buy. We don’t keep stashes of money around the office. When we suddenly need a large sum of money to make a buy or something, that’s the route we take. I think [with the Brink’s transaction] you’ve proved with that single fact that he had a relationship with the police. He was either a CI or an agent.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XIMW1wH_3Rw&ab_channel=Maclean%27s

Wortman arrives at Brinks yard on March 30, 2020

Unlisted0 Comments

Wortman inside the Brinks yard on March 30, 2020

Unlisted3 Comments

A Canadian retail banking expert speaking on condition that they not be identified says it is unlikely that Wortman was cashing out his own savings when he collected the money from Brinks after the money was transferred from CIBC Intria.

“When you come into my branch and you want a ton of cash, then I say, you gotta give us a couple of days. We put in our Brink’s order, I order the money through Brink’s, then when the money arrives, you come back into the branch, I bring you into a back room and I count the money out for you,” the banking expert said. “Sending someone to Brink’s to get the money? I’ve never heard of that before. The reason is, if I’m the banker, and you’ve deposited your savings in my bank branch, I’m responsible for making sure the money goes to the right person. If you want this money, I’m going to verify your identity and document that. I can’t do that if I’m transferring the money to Brink’s.”

In response to detailed questions from Maclean’s about the transaction, a CIBC spokesperson replied via email: “Our hearts and thoughts are with the families and the entire community as they deal with this senseless tragedy and loss. Unfortunately we are not able to comment on specific client matters.” Brinks did not reply to questions about the transaction.

The banking expert speculates that the RCMP could keep transactions relatively quiet by going through Brink’s instead of a bank to transfer money to a confidential informant or an agent.

“You can imagine that if someone comes in with large sums of cash, that stuff is not kept quiet. You don’t want that. Maybe what the RCMP was doing is they thought they could keep things quieter simply by transferring funds via Brink’s.”

At a press briefing on June 4, the RCMP’s Campbell seemed to rule out the possibility that Wortman was a confidential informant for the force. “The gunman was never associated to the RCMP as a volunteer or auxiliary police officer, nor did the RCMP ever have any special relationship with the gunman of any kind.”

The RCMP Operations Manual, a copy of which was obtained by Maclean’s, authorizes the force to mislead all but the courts in order to conceal the identity of confidential informants and agent sources.

“The identity of a source must be protected at all times except when the administration of justice requires otherwise, i.e. a member cannot mislead a court in any proceeding in order to protect a source.”

A spokeswoman for the Nova Scotia RCMP declined further comment after Maclean’s reported on the financial transaction.

“This is still an active, ongoing investigation,” said Cpl. Jennifer Clarke in an email on Friday. “All investigative avenues and possibilities continue to be explored, analyzed, and processed with due diligence. This is to ensure that the integrity of the investigation is not compromised. We cannot release anything more related to your questions.”

Maclean’s reported earlier this week that sources say Wortman had social relationships with Hells Angels, and with a neighbour, Peter Alan Griffon, who recently finished serving part of a seven-year sentence for drug and firearm offences linked to La Familia, a Mexican cartel. Sources say Griffon printed the decals that Wortman used on the replica RCMP cruiser he used in his rampage.

Sources say that RCMP in New Brunswick, not Nova Scotia, recently took over operational control of investigations into outlaw bikers in the Maritimes, which means that Nova Scotia Mounties may not have been aware of any connection to Wortman.

The RCMP Operations Manual identifies two types of sources: informant sources and agent sources. A law enforcement source said the force uses Brink’s to make large payments to agent sources, not informant sources.

“Informants are never paid more than a couple hundred at a time,” said a person briefed on RCMP operations. “Anything over $10,000 is agent money.”

Agents typically have greater responsibilities than informants. Only officers who have received specialized training are allowed to handle agents.

“An agent source is a person tasked by investigators to assist in the development of target operations,” says the manual. “Direct involvement and association with a target may result in his/her becoming a material and compellable witness, ie. a source used to introduce undercover operations, act as a courier for controlled delivers or act in place of an RCMP undercover operator by obtaining evidence.”

If the money was a transfer from the RCMP to an agent, there would be a paper trail through FINTRAC, the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada, which tracks large cash transactions and suspicious transactions.

“Brink’s does the FINTRAC paperwork saying it’s coming from us, it’s from a chartered bank, and the RCMP liaison at FINTRAC signs off, handles the paperwork,” said a source briefed on the system. “The RCMP guys clear it or they refer it for further investigation. They manually clear those FINTRAC reports coming from Brink’s related to paid agents.”

The RCMP Operations Manual requires officers handling confidential informants and agents to send reports to the director of the Covert Operations Branch at National Headquarters.

Headquarters’ media relations office said in an email Friday that Campbell’s statement that the force never had a “special relationship” with Wortman “still stands.”

The attorney general of Nova Scotia, former RCMP staff sergeant Mark Furey, has said the province is in talks with Ottawa about a joint federal-provincial inquiry or review of Wortman’s murderous rampage.

Furey’s office did not reply before deadline to a question about whether the terms of the inquiry would allow inquiry counsel to pierce the powerful legal privilege that attaches to confidential informants.

Family members of the victims have complained that the process is dragging out. As calls for an inquiry mount, so does speculation about what happened, among both the general public and the RCMP.

One former Mountie says he doesn’t understand why Wortman would turn against the Mounties if they were paying him. “What seems inconsistent to me is why are you going to bite the hand that feeds you? If he’s getting money, and that’s a lot of money for an agent, or a CI, that part doesn’t make sense to me.”

The former investigator pointed out that if Wortman was acting for the RCMP, and receiving that amount of money, he would eventually be expected to testify.

“If he was an agent, he should show up on a witness docket.”

But another Mountie says, “This guy always wanted to be a Mountie. He was acting like a Mountie. He was doing Mountie things. It’s clear to me that something went wrong.”

Contact our reporters:

Stephen Maher: stephenjamesmaher@gmail.com

Shannon Gormley: shannon.n.gormley@gmail.com

Paul Palango: paulpalango@eastlink.ca

Time for real answers on the Nova Scotia mass murder

Paul Wells: A full judicial inquiry into the April shooting is now essential. It must be robust, with real power to get to the truth.

A still from a video showing Gabriel Wortman in the Brink's yard on March 30, 2020.

We are faced, perhaps only temporarily, with a familiar Canadian paradox: everyone says they want something to happen, but it isn’t happening.

The “something” is a rigorous public inquiry into a horrible shooting spree that spanned two days and killed 22 people in Nova Scotia in mid-April. It was the worst mass murder in Canadian history. It was lurid in its weirdness. The gunman, Gabriel Wortman, spent two days driving around in a convincing replica RCMP vehicle, shooting at whim, while the force he was imitating and dodging failed to send out a more comprehensive emergency alert than their Twitter warnings, one that might have saved more lives. In the midst of the carnage, two actual RCMP officers apparently fired their weapons into the walls of a firehall in Onslow for reasons that remain unknown.

New reporting for Maclean’s by Shannon Gormley, Stephen Maher and Paul Palango raises troubling new questions about Wortman’s possible ties to organized crime and, especially, to the RCMP itself. This reporting is attracting a lot of attention and, here and there, vigorous online debate. This Twitter thread, for instance, asks hard questions about our latest story.

The questions raised by our investigative team including Paul Palango, author of three best-selling books (here, here and here) about the troubling history of the RCMP, are backed by a solid and growing network of well-informed sources. But past a certain point, even superb reporting can’t provide authoritative answers. That work is properly left to duly mandated public authorities, usually wearing judges’ robes. Some people, reading the most recent Maclean’s reporting, have said the RCMP has a lot of questions to answer. Unfortunately there is no reason to take any answer from the RCMP on faith. It’s time for a full judicial inquiry.

READ MORE: The Nova Scotia killer had ties to criminals and withdrew a huge sum of cash before the shooting

Everyone agrees! From Nova Scotia premier Stephen McNeil to the latest embattled RCMP commissioner to three Trudeau-appointed Nova Scotia senators to anguished families of the murdered to, I mean sort of, the Prime Minister. But so far there is no inquiry.

As is reliably always the case with this Instagram-obsessed and reflexively stonewalling regime, the best information about what the Trudeau government is up to is coming from somebody else, in this case the Nova Scotia government. An inquiry’s coming soon, Nova Scotia attorney general Mark Furey said two weeks ago. Really soon, he said on Thursday. (It’s unclear why Furey hasn’t been working with his direct counterpart, the attorney general of Canada, who is reputed to be David Lametti, although on most days it’s hard to be sure. On the bright side, I can report that Lametti has been kayaking.)

Unfortunately even the noises emanating from the McNeil government, the second-last Liberal provincial government in the country, are unnerving. There is much talk about a “restorative” approach that would investigate broad societal issues. But in many cases the families of the murdered aren’t crying out for a healing circle. They are demanding answers on the facts. “The amount of information being kept from us is deplorable,” Darcy Dobson, whose mother Gabriel Wortman shot dead, told the CBC.

So with all due respect for the complexity of setting up any inquiry, it is time for Justin Trudeau to make Mark Furey’s repeated predictions of a joint federal-provincial inquiry come true. The inquiry must be robust, with real power to get to the truth, and no stonewalling. Which means it will need to constitute a surprising and wholly uncharacteristic act of transparency from this Prime Minister.

What we are used to seeing from this Prime Minister is Liberal MPs on the Justice committee enforcing a coverup in the SNC-Lavalin affair. We are used to the ethics commissioner reporting that nine witnesses with material information were forbidden from testifying by the Privy Council Office. We are used to this Prime Minister responding to the Nova Scotia killings by trying to tell reporters what they could and couldn’t report. We are used to a Prime Minister who has replaced Question Period in the House of Commons with daily briefings to reporters whose tone is deferential, who are limited to a single follow-up per question, and who don’t get to speak until Trudeau has announced the latest injection of dozens of millions of dollars into the national mood. Canadians see this Prime Minister, and they are used to watching him be the only person in a crowd who thinks he is answering a question.

That’s not good enough now. It’s time for a real inquiry with real powers to provide real answers to a slaughter whose central figure’s ties to the federal police force that took two days to stop him are in question. Now, please.

Cracks are forming in the RCMP cone of silence

Photo: Joan Baxter

It has been about five weeks since the Nova Scotia massacre, five long weeks during which the Royal Canadian Mounted Police have cowered inside a cone of silence.

Compare its approach to how police forces around the world have typically handled similar events. From Paris to Toronto to just about Anywhere USA, the police are quick to inform the public about what has transpired and about key information about the perpetrator or perpetrators. Little, if anything, is hidden.

So what’s the problem here?

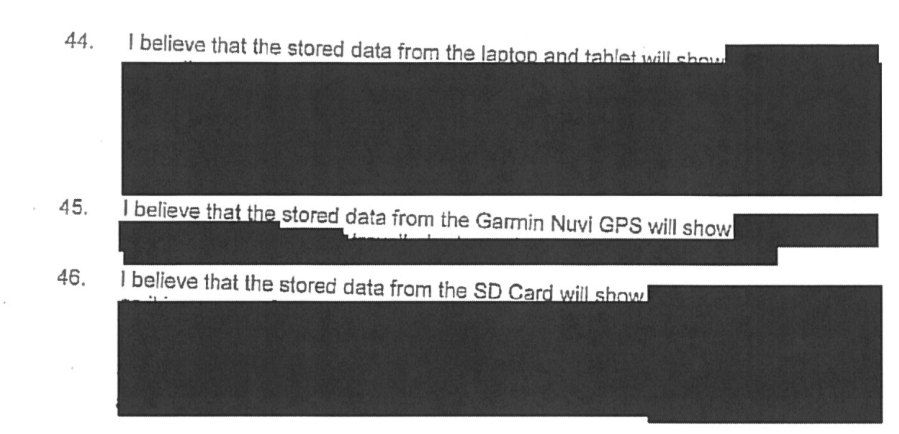

From the outset the RCMP right up to Commissioner Brenda Lucki seems determined to stall for time and control the narrative of this story. They have forced the media to go to court to find out what was in the applications for search warrants executed after the shootings. The law states that such information should be readily available to the public.

The Mounties have also taken refuge behind its claim that it has commissioned a psychological profile of the gunman and can’t say anything at this time. It kind of sounds like then candidate Donald Trump’s claim in 2016 that he couldn‘t reveal his tax filings because they were under audit.

In my long experience of writing about the RCMP, now into its fourth decade, I’ve become accustomed to the typical response I receive after something is published. Some are praiseworthy, many are castigating, including current and former members of the RCMP.

What I’ve learned and described is that RCMP culture is cult-like. There is an almost mindless commitment to the force. “There is no such thing as an ex-Mountie,” I once wrote, because even retired Mounties seem compelled to protect the image of the force.

Since publishing an opinion piece last week on Macleans.ca, I’ve witnessed the typical gamut of comment. Among them, Philip Black wrote:

The RCMP are not perfect, but does that justify the rampant jumping to conclusions and the widespread RCMP bashing.

And Brenda Carr, a 911 dispatcher had this to say:

… people who do not work in this profession can only surmise what it is like and what it takes to do this job. And no one is looking for praise. And on the same note, no one is looking for criticism. They did their best. And you do not know nor will you ever know what these men and women did to stop this monster. This is a time for healing. This article is not helping, it is only hurting.

But to my surprise, many others have contacted me who don’t fit the normal profile in that a number of them were current or retired RCMP and other law enforcement officials.

“I’ve read everything you’ve written over the years and while I agreed with some of it, a lot of it just made me mad,” said one former high-ranking RCMP executive. “But now, I have to admit that I agree with you. The RCMP is broken. It’s not ready. It’s a danger to the public and its own members.”

That Mounties sentiments were echoed by another former Mountie, Calvin Lawrence, who first served in the Halifax police department before joining the RCMP, where he had a long career. He is the author of a book, Black Cop. He amplified the comment about readiness.

After the murder of three Mounties in Moncton in 2014, the RCMP changed its policies and all police officers were given long guns.

Lawrence says that while the Mounties carry the guns, they don’t likely know how to use them in a desperate situation. He says that while the RCMP talks a good game about its training, in reality a lot is left to be desired.

I suggested to him that the first Mounties to respond to the scene, particularly the supervisor, a corporal, may have been frozen in place, not knowing what action to take.

“That doesn’t surprise me at all,” Lawrence said. “You would think they had something in place to respond to crazies,” Lawrence said. “They probably put something in writing but didn’t practice it…. Tactical training costs money. The officers had the guns but didn’t know how to use them.”

But the most interesting call of all arrived with a cryptic description on the cell phone call display that I had never seen before.

The caller, who could best be described as a Deep Throat whistleblower, was obviously nervous. I will call him “he” from now on because there are more hes than shes in the law enforcement world.

“This is the first time I’ve ever done something like this,” he said. “But I felt I have to do something.”

He said he was calling me to encourage the media to keep asking questions: “Don’t give up.”

When I told him that I and others who are pursuing the story have a thousand questions about what went wrong, from the indecision at Portapique Beach Road, the apparent communications debacle where not only the RCMP brass was not alerted to the seriousness of the situation but also the public.

I asked him why the premier of Nova Scotia and the province’s Attorney General were reluctant to call a public inquiry.

“Is it because Premier McNeil has relatives in policing, that the Attorney General is an ex-RCMP and that there are ex-RCMP in the police services branch?”

“That’s not it,” he said. “It’s about the money.”

So I switched to events.

“Why was Heidi Stevenson alone in her car?”

“I know what happened to Heidi,” he said. “It was just bad luck. But, you’re right, she shouldn’t have been there.”

But that wasn’t why he called.

“All that stuff will eventually come out,” he said.

The real issue, he said, was what the police are hiding about their previous knowledge about the gunman.

“Make requests about Wortman and what the police knew about him.”

“RCMP or Halifax?”

“Just keep asking questions and filing access requests.”

I tried to push him. I pointed out that while the COVID-19 epidemic has hampered the news gathering abilities of the major media, there was a lot of good work being done by an array of organizations from the on-line Halifax Examiner to Canadian Press and even the notorious Frank Magazine. To date the various entities have reported on everything from the gunman’s quirks, threats to others, illegal guns, replica Mountie cars, possible cigarette smuggling and even the murder of someone in the United States, among other things. The man killed 22 people, including a police officer in cold blood, so he doesn’t have a reputation to besmirch. In the absence of the RCMP’s official story about him, speculation becomes rampant.

“It seemed to me from the outset that he may have killed other people in the past,” I said.

The whistleblower just hmmmed.

“There’s something they are hiding that will blow the lid right off this thing,” the whistleblower reiterated. “I can’t tell you what it is. I shouldn’t even be telling you this. Just keep pushing.”

When I ran all this by Maclean’s writer Stephen Maher, he immediately added another possibility. “Maybe he was a CI.”

A confidential informant? With a licence to kill?

It’s a crazy idea but in the absence of facts from the RCMP people will talk.

That’s the situation we are in.

This week the RCMP and its government lawyers have continued to obstruct the information process, insisting upon redacting information contained in the applications for its search warrants.

And then there is the psychological assessment or “autopsy” of the gunman. Well here’s my independent analysis.

He likely wet the bed when he was young. He had a fascination with fire. He tortured little animals. He likely had an accident and sustained a seemingly minor head injury in his youth. He suffered from undetected frontal lobe brain damage. He had low self-esteem but masked that with a superficial outward face. He grew into a malignant narcissist. Like many serial killers and mass murderers, he had a fascination with policing but becoming a security guard was beneath his station. He was a misogynist, largely because he had sexual orientation issues. He had no empathy for anyone and was controlling. I could go on, but….

That’s it. Send the cheque to a charity of your choice.

That being done, Commissioner Lucki, what’s the BIG SECRET?

Paul Palango is a former senior editor at the Globe and Mail and author of three books on the RCMP. He lives in Chester Basin.

The Halifax Examiner is an advertising-free, subscriber-supported news site. Your subscription makes this work possible; please subscribe.

Some people have asked that we additionally allow for one-time donations from readers, so we’ve created that opportunity, via the PayPal button below. We also accept e-transfers, cheques, and donations with your credit card; please contact iris “at” halifaxexaminer “dot” ca for details.

Thank you!

Comments

Mark Furey and the RCMP’s secret army of Smurfs

Justice Minister Mark Furey. Photo: Jennifer Henderson

It has been six weeks since the Nova Scotia massacre and as the RCMP dribbles out the official facts of the investigation, many have wondered why the Nova Scotia government has been reluctant to call for a public inquiry.

Premier Stephen McNeil has tried to fob it all off on Ottawa, but Prime Minister Justin Trudeau last week seemed reluctant to catch the steaming hot potato.

And then there are questions about Justice Minister Mark Furey. He was a Mountie for 36 years before he became a politician. And now he’s in charge of all matters of legal and policing issues from soup to nuts.

From what I know of him in passing, Furey is an outwardly nice guy, a sort of Boy Scout on steroids. But as my late Sicilian mother, Lea, used to say: “Who is he when he’s at home?”

Who knows?

Furey collects a healthy pension from his Mountie days and is revered in Mountie circles as one who made a life for himself in the outside world. He says he does not have a conflict. But does he? He says he can deal dispassionately with the enormous task before him. But can he?

The powerful, mind-controlling threads of Mountie DNA are instilled in every recruit who passes through Depot, the RCMP training facility at Regina. Among the first things a young Mountie is taught in his or her indoctrination is that the RCMP is “The Silent Force.” It does not answer or explain itself but lets the public speak for the organization.

That sounds high-minded and confident. It might appear to the casual observer that all kinds of Canadians leap to defend the RCMP in the time of crisis, but dig deeper and you begin to understand that the seemingly spontaneous defence of the force and its actions is anything but. The force is being a little too disingenuous.

In my 2008 book I devoted a chapter to the Secret Armies of the RCMP. It told how the force directs dialogue and policy from behind the scenes, mostly covertly, sometimes overtly. This so-called army consists of current and retired Mounties, their families, friends, and a general coterie of typical right-wing zealots. In the United States, there is a two-word phrase to describe these sorts: Trump supporters. In Canada, they advocate against change, reform or investigation of the RCMP.

It’s as if they sit around the Lodge sipping tea and cordials and then charge out on their high horses in a cult-like mission to lobby and silence critics and other perceived threats to the force, particularly political ones.

For a current example of this, consider Alistair Macintyre. He is the retired assistant commissioner, once the Number Two commander in British Columbia. Last month he played the Smurf and wrote an open letter to hint at salacious behaviour by the mayor of Surrey. The real issue is that the Surrey city council has voted to replace the Mounties with a city force next year, which is huge blow to the Mounties. Surrey employs more Mounties than all of Nova Scotia.

Over the past couple of decades, many in the RCMP, municipal and provincial police forces, have told me about how they’ve been bullied and intimidated or afraid of the force. Most are so fearful that they refuse to go on the record about it.

“The Mounties play dirty,” Edgar McLeod told me for Dispersing the Fog. He is the founding police chief of the Cape Breton Regional Police department and the head of the Atlantic Police Academy at Holland College in Prince Edward Island. Friday, in an interview from his Summerside, PEI home, he elaborated: “Governments at both the federal and provincial level have failed in their duty to hold them accountable.”

Another person extremely familiar with RCMP thinking said this: “The biggest fear the RCMP has is to be held accountable. It believes that no one can tell the force what to do.” This source is close to the inner circle in Ottawa and I’ve chosen not to name him/her, but we will call the source Dudley, from now on. Dudley is more valuable to the readers keeping his ear to the ground.

“At this point,” Dudley says, “there is only two ways to go: save the RCMP or shoot it.”

The stakes are high and the Smurfs are coming out of the woodwork trying to affect, narrow, and even shut down public discourse. One tactic they have is to conflate any criticism of the force and the system in which it operates, which is my focus, down to an attack on officers on the street, which is not.

After I did a radio interview in Halifax, the Smurfs started calling in, suggesting that because I wasn’t physically at Portapique Road, I had no right to be commenting on what happened.

That evening, just after midnight, a person identifying himself as a retired Mountie named Staff-Sgt. Eric Howard contacted me. In a shirty rant, Howard demanded that I provide a resume showing my expertise before I be allowed to comment on matters regarding Mountie tactics, operations, and human resources. “Should you continue to make statements without the expertise to back it up, you are just prostituting yourself for money or attention,” Howard wrote. “Think about this before commenting on any situation. I await your reply and resume.”

He’s still waiting.

Later that day I had a pre interview with another radio show host. I could smell the Smurf on him. We booked a time for the next day.

That night, just after midnight again, I got another missile fired at me from R. G. Bryce, who claimed to be a long time and current member of the RCMP.

Calvin Lawrence

In the officious sounding comment Bryce challenged former Halifax and RCMP officer Calvin Lawrence for what he had to say about the readiness of the Mounties in dealing with such a horrific situation that began on Portapique Beach Road. On Facebook, Lawrence continues to be pummelled by the Smurfs for speaking out.

Bryce wrote: “As a former member, you should be supportive to your fellow members ….so to make myself clear, shut your mouth, because you don’t have a clue what you’re talking about.”

He gave a perfect demonstration of how the Smurfs talk when they want to control the narrative.

When I appeared on the radio the next day, I was prepared for the expected attack. The first question could have come right out of Staff-Sgt. Eric Howard’s mouth. I batted down by reading the exact response I had sent to Howard, which began: “Sir: Many of your retired superiors say I’m 100 per cent right…. The deep seated problems afflicting the RCMP are obvious and a matter of public interest.”

Over the decades I have experienced these attacks in both an overt and covert way. Some of it was reported in 2008 in the Georgia Strait newspaper in Vancouver, among other places.

What’s different this time, is a sense of desperation by the RCMP. As I popped my head up in this story, I got a notice from Linked In that a number of top Mounties in Ottawa were interested in me, including Ted Broadhurst, an Ottawa-based cyber special projects officer in federal policing criminal investigations. What? Was he looking to hire me or work for me? Not likely.

Paranoid? No, the curious thing was that Broadhurst is an expert on doing sneaky things. His public resume shows he was in the special services covert operations branch, tactical internet open source and other creepy things. He’s a guy who should know how to cover his tracks, but he didn’t. Why? Maybe he was trying to spook me. That’s what the Mounties tend to do.

To understand how the Mounties have worked behind the scenes in Nova Scotia, we need to go back to the years prior to the 2012 signing of the latest 20-year contract with the RCMP in Nova Scotia. At that time then Halifax police chief Frank Beazley noticed severe discrepancies on the rosters of the RCMP detachments who had the contract to police Halifax County outside the city. Although taxpayers were footing the bill for a certain number of officers, there were consistently fewer working. Beazley told me: “We began to look at RCMP staffing in the area and what individual officers were doing. Beside some officer’s names we’d find a zero for time, zero files, zero investigations, even though they were listed as being on the roster. We asked the Mounties what was going on and they wouldn’t tell us. We sent 1,500 emails to the RCMP about this, but never got one reply. Eventually we learned that one of the officers who was on our roster was also on the roster of a force in B.C. Another was on a federal police roster, and so on.”

You would think that such shenanigans would generate considerable interest in the provincial government. The Mountie shell game was essentially a fraud and still is, as was pointed out in an excellent CTV story on Sunday. But the New Democratic Party Justice Minister at the time was Ross Landry, an ex-Mountie. He pretended to hear the arguments about why the RCMP should be replaced at least in Halifax, but then pushed through a new contract which pretty well gave the RCMP everything it wanted and needed. If the Mounties had lost the Halifax County contract, they were effectively finished in the province.

Now Mark Furey is the minister of all things touching on the law in Nova Scotia. He is the point man when it comes to holding the RCMP accountable. It’s obvious that there are a thousand horrible questions for which we need answers. At the same time, the Mounties and their fervent Trump-like supporters are literally saying: “Move along. Nothing to see here.”

But there is plenty to see and to suggest otherwise is pure negligence. If anyone who is a threat to the Mounties and doesn’t say the right thing is attacked, how is Furey resisting this? Does he have some sort of immunity from overt and covert RCMP pressure?

We need to know what exactly the Mounties did and didn’t do over those two days.

How many Mounties were supposed to be on the roster of the various detachments and communications centres and how many of them were actually there that weekend?

Who was in charge at every moment?

Why did the RCMP not call in the local forces in Truro, Amherst, Halifax, and New Glasgow and environs?

Conversely, why have the chiefs of those same local forces been closed lipped about what happened? Is it the thin blue line in action? Or is there something going on between those forces and the Mounties that the public doesn’t know about? Did that something affect the decision-making process that night.?

A big question: Why did the Halifax Police Chief refuse to call in his emergency response team? Why did he tell them not to shoot the gunman?

How and why was Heidi Stevenson at the traffic circle in Shubenacadie at the time she was murdered?

What was the seemingly hidden relationship between the gunman and the police?

There are more questions, many more, and I suspect they will lead down a dark hole for the Mounties.

At this particularly delicate time in its history, when its very structure across the country is at stake, the RCMP will fight tooth and nail to maintain the status quo.

That means it will resist a public inquiry. Even its house union has taken that position, which should tell you something.

Can Mark Furey rise above all this, be the bigger man and be totally objective?

Or is he just another dyed-in-the-wool Mountie Smurf who, given the choice between defending the public interest or those of the Mounties, slyly tilts to the side of the red coats.

Furey says he doesn’t have a conflict, but the smart thing would be for him to recuse himself and let Caesar’s wife, someone above suspicion, take over the file.

Paul Palango is a former senior editor at the Globe and Mail and author of three books on the RCMP. He lives in Chester Basin.

The Halifax Examiner is an advertising-free, subscriber-supported news site. Your subscription makes this work possible; please subscribe.

Some people have asked that we additionally allow for one-time donations from readers, so we’ve created that opportunity, via the PayPal button below. We also accept e-transfers, cheques, and donations with your credit card; please contact iris “at” halifaxexaminer “dot” ca for details.

Thank you!

Comments

https://www.halifaxexaminer.ca/featured/calvin-lawrence-black-panther-partys-unlikely-cub/

https://stephenkimber.com/calvin-lawrence-black-panther-partys-unlikely-cub/

Calvin Lawrence: Black Panther Party’s ‘unlikely cub’

His hiring as a Halifax police officer in 1969 happened only because the city feared what might happen if it didn’t at least pay lip service to inclusion. But over the course of his 36-year policing career, Calvin Lawrence proved a more than worthy fighter against racism.

The 1969 Halifax Police graduating class. Calvin Lawrence is in the second row, third from the left.

The 1969 Halifax Police graduating class. Calvin Lawrence is in the second row, third from the left. Calvin Lawrence remembers the life-altering moment well. It was an early summer day in 1968 and Calvin, then 19 and still a student, was hanging out at Creighton and Gerrish Streets, “one of my favourite corners,” with his good friend Ricky Smith. A big Lincoln car filled with three senior members of the black community, including ex-boxer and community leader Buddy Daye, pulled up beside them.

“C’mon, get in boys,” one of the men said. “We’re going somewhere.”

Somewhere turned out to be the old Halifax police station on Brunswick Street. As Lawrence recounts the story in Black Cop (James Lorimer & Company Ltd.) — his excellent and well-worth-the-read account of his 36-year career as a police officer with both the Halifax force and the RCMP — “we were led down a squeaky clean hallway into what seemed like a prearranged meeting” with the city’s then-chief of police, Verdon Mitchell.

For a while, the two young men were just puzzled observers to a 90-minute conversation with the chief about policing in Halifax. “Finally,” Lawrence writes, “Buddy looked hard at Ricky and me. Without taking his eyes off of us, Buddy said to Chief Mitchell, ‘Perhaps you can give these two young men summer jobs.’”

For a young black man at the time, it was — or should have been — a golden opportunity.

But in 1968, Halifax had become a seething cauldron of racial tensions. The city’s destruction of Africville had been “disgusting,” Lawrence recalls. “It was shameful.”

The local black community, which had historically accepted racist behaviour as an “immovable object,” finally rebeled. “The anger of the community spilled out of the confines of the church and out of the established avenues of accepted activism.” There were riots — minor compared to what was happening in other cities in North America, but still cataclysmic for Halifax. The Black Panthers came to town, and brought with them the real possibility of organized, black-led violence. “Their tactics went beyond marching, singing, praying and demonstrating for change.”

All of that, of course, “scared the hell out of the city of Halifax and the Halifax police department.” And, in its way, it had led to that meeting in the chief’s office and to the offer of a summer job with the Halifax police department for Calvin Lawrence. “We were the unlikely cubs of the Black Panther Party’s time in Nova Scotia.”

“I was to be thrust into the eye of the storm that was pitting the city police against the black community,” he writes in the book. “What I didn’t know then — but what I do know now — was that I was a bargaining chip.” On the one hand, he and his friend were being offered up to the chief as potential young black police officers, a way out of the turmoil. “On the other side was the fear of the dark — the unknown of the Black Panther Party. We were just two little pieces of a puzzle, but the message to the white power structure was clear — put these boys in uniform, or the alternative might be more than you can handle.”