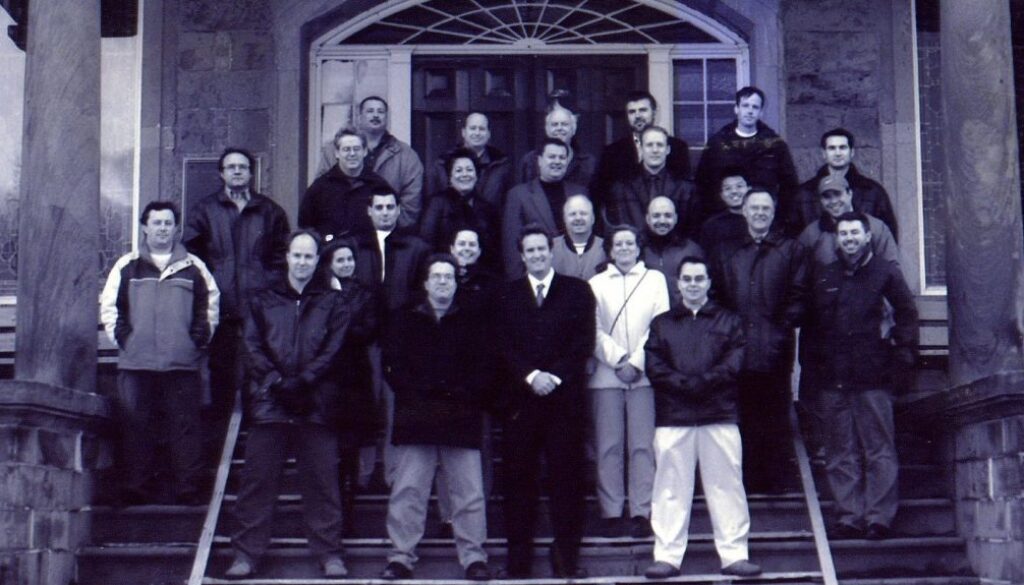

The Q1 Labs team in 2003 at UNB's Old Arts building. Front row, from

left: Dwight Spencer, Sandy Bird, Brian Flood and Chris Newton in front.

Image: courtesy of Dwight Spencer.

The Q1 Labs team in 2003 at UNB's Old Arts building. Front row, from

left: Dwight Spencer, Sandy Bird, Brian Flood and Chris Newton in front.

Image: courtesy of Dwight Spencer. When Brian Flood entered Chris Newton’s life, it gave the younger man a bracing whiff of adventure, but also a tremor of trepidation. He was 28, settled in his university job, newly married to his wife, Tracey, thinking about a family, and in the process of buying a house — and now this guy Brian Flood wanted him to give it all up and launch a company. “I was scared as shit,” Newton would say later. “And you’re telling me I am leaving a position where I could work for 30 years to join a startup with no money or sales?”

Newton knew how tenacious Flood would be in his counterargument, that this was a life-changing opportunity. “But I felt I might quit my job and a month later, I might be out of work. Then I’d be losing my house. I thought I’d probably have to say no,” he concluded.

After some months, the moment of decision came: his university boss, Greg Sprague, called to say he should make a choice, leave to join the startup or commit to work full-time at UNB. Newton was torn. Then Sprague offered a suggestion — the university was willing to give him an unpaid leave of absence of two years, allowing him to try the new venture. Newton was enthusiastic — what was there to lose? “I would not be getting paid but I knew if things didn’t work out, I could just come back to my job.”

He now concludes that this was the critical step that got his new venture off the ground. Many people in university or public service come up with great ideas but hesitate to pursue them for fear of failing without any safety net for themselves and their families. This was a way to provide that buffer.

He feels governments in particular should be open to dispensing leaves of absence, more than private-sector companies, which might feel threatened competitively by allowing key personnel to take two years’ leave (though it would probably work well for many private companies too). Looking back on UNB’s offer, “I don’t think I understood at the time how important that would be.” He could go out in the world and know he had options if the thing didn’t work out.

PODCAST: Gordon Pitts On The ‘Code-fathers’ And The Billion-Dollar Sales Of Q1 Labs And Radian6

Newton had to make other decisions. He had poured himself into developing his Symon idea, working on his own, but now it was more than he could handle. Early in the process, he reached out to his friends Sandy Bird and Dwight Spencer; Bird was still working at the university and Dwight at a government technology job. They had been buddies for years and were about to become partners.

It was intense. The old pattern continued: the trio were working at their jobs full-time and heading home at night to work some more. Newton is derisive of entrepreneurs who think they can launch companies working 9-to-5 days. The UNB trio would come home from their jobs around five-thirty, spend time with families and friends, and then get online, working with each other, from eight o’clock or so, till 1:00 a.m. or later.

“We had this chatting system and we could tell when someone fell asleep,” Newton recalls. “You could see their keystrokes go in a line — l-l-l-l-l — and you’d think, ‘Uh-oh, Dwight has fallen asleep on his keyboard.’”

Newton’s message to young entrepreneurs is, ‘If it doesn’t keep you up at night, it is probably not worth doing.’ A great new idea can’t be easy. Anything of value in technology has to be hard, and yet it can’t be so hard that it seems impossible.

Even after the company was founded, Dwight and Sandy were toiling away at their old jobs. It was about a year and a half before they quit to go full-time with the new company. There was no longer talk of graduating; they were too busy. In the future they would cover up their lack of degrees by simply saying, “We attended UNB.”

All these moves laid the foundations for the new company that Newton, Flood and the university were trying to put together. It was a major step for UNB and for David Foord, the technology-transfer officer who was balancing a delicate issue. How do you structure an agreement that protects the university’s interests in intellectual property but also rewards and offers incentives for these young people?

If Newton and his friends had been faculty members, they would have clearly owned the intellectual property. But Symon had been developed while they were employees of UNB, which meant that, strictly speaking, UNB owned the technology. And yet it was developed largely on their own time, while using the university’s networks to test and develop the programs.

Foord pushed toward the model he had seen on the West Coast. Instead of demanding royalties, UNB would assign the intellectual property to a new company as part of a founders’ deal, and then take equity in the company in return for signing rights.

The university’s stake was about 5 percent, according to various sources, and the rest of the ownership was divided up largely among Brian Flood — the major financial investor with the majority stake — Chris Newton, Sandy Bird and Dwight Spencer. The three young developers collectively held about a third of the ownership, with Newton taking the largest cut of the three. Two other smaller shareholders came from Brian Flood’s network: Steve Beatty had been Flood’s accountant in his restaurants, and lawyer Linda Fung had been one of Flood’s guides through Silicon Valley and did a lot of the legal work around the formation of Q1 Labs. Fung ended her active involvement in the early stages, while Beatty would remain chief financial officer for a period.

The new firm, Q1 Labs, could still use the university network for research and product demonstrations, and the university could develop research papers based on the work. In the dry wording of the university website, “In April 2001, [the office of research services] transferred the UNB-owned technology to Q1 Labs for equity in the company and the right to continue to use the technology for research and educational purposes. . . . Q1 Labs established R&D facilities in New Brunswick and formed an alliance with UNB whereby seventeen live networks were available for product testing and research.”

The deal underlined the role of the university in the early life of Q1 Labs. To call it supportive would be to underplay its importance. There was a lot of trial and error — the university and the founders had never done this type of thing before. Brian Flood may have published a book, sold 3M products or run a restaurant, but he had never launched a startup tech company with a groundbreaking product, young co-founders and a university backer. A UNB professor named Ali Ghorbani, emerging as a research leader in cybersecurity, effectively became part of the Q1 team, though he was not officially employed by the company.

The other critical factor was getting the funding to turn this idea into reality. Flood beat the bushes in New Brunswick and far afield to assemble a group of what’s known as angel investors. The term “angels” is not celestial but entirely materialistic — it was originally used to describe the collection of friends, family and theatre groupies who funded the incubation of new Broadway plays. Later it was extended to the people who, from love or loyalty, extend small amounts to get a startup off the ground. “Friends, family and fools,” says one tech veteran.

Brian Flood was milking cash flow from his restaurants to fund the high-tech venture and was maxed out on a slew of credit cards, just staying ahead of the banks. Meanwhile, the UNB kids and their families had nothing to give but time and sweat.

The most fertile field of funding came from the faculty, alumni and supporters of UNB. This was the critical moment when you needed true believers who were also realistic enough to know the whole project could sink like a stone.

Jane Fritz was the very definition of true believer. She was dean of the faculty of computer science that day when Brian Flood burst into her office with the news that he had found his startup baby, right here under her nose with one of her favourite students, Chris Newton. Soon Flood would be coming back and asking for money.

Fritz was an easy touch. She had an affinity for young men and women with bright ideas. “I love my geeks,” she says. “I’ve taught thousands of geeks, and they’re just awesome people. I love what they do.” She is a pioneering academic in computer science who had come to Fredericton in 1970. A UNB masters of science grad who got her PhD in England, she had followed her metallurgist-turned-systems-consultant husband back to New Brunswick, where he was helping install the province’s first medicare system. She stayed to become a pillar of UNB’s outstanding computer science faculty.

She recalls that when she came to Fredericton in 1970, there was one computer in the government and one computer at the university— and NB Power used it as well. “It was the biggest one east of Montreal. And that was it.”

She was a difference maker in the province, planting the seeds of a knowledge industry. Then along came Chris Newton and his friends, who, initially as part of their internships, ended up in the Computing Centre. Her recollection is that she and her husband put $15,000 into Newton’s company, not a lot but enough to make a difference in the early days of Q1 Labs. It took a long time before they saw any return, but Fritz has since then done other deals for other students. They were not as fruitful, but that is what you do when you truly believe in people.

Meanwhile, UNB officials helped Brian Flood comb through lists of alumni who might contribute, reaching into the Bay Street–Toronto crowd to find graduates with a tolerance for risk. In the end, Flood had $770,000 U.S. of seed money to work with, of which he had contributed about $400,000 of his own. He had recruited a dozen angels, seven of whom had contributed $10,000 U.S. or so, but two contributors came in at $100,000 and another two at $50,000. The angel investors took convertible debentures — essentially securities convertible later into common shares. It all helped, Flood said, and it was fortunate that there wasn’t a lot of competition for cash. “We were in a bubble up here, the only game in town.”

This is an excerpt from “Unicorn in the Woods” by Gordon Pitts. Reprinted with permission from Goose Lane Editions.

Brian is a lifelong New Brunswick resident. In 2001, Brian became the business founder and CEO of tech start-up Q1 Labs, a security intelligence so ware fi rm that over a period of ten years, grew to employ hundreds of New Brunswickers. In 2011, Q1 Labs was bought by IBM in what would become one of the largest acquisitions in New Brunswick’s history.

Brian, qui habite depuis toujours au Nouveau-Brunswick, était président-directeur général de l’entreprise Q1 Labs, fondée par lui-même en 2001. Q1 Labs se spécialisait dans les logiciels de renseignement de sécurité; en dix ans, l’entreprise a employé des centaines de Néo-Brunswickois. IBM a acquis Q1 Labs en 2011, ce qui représente l’une des plus importantes acquisitions jamais réalisées au Nouveau-Brunswick.

Speaker Series Online with Brian Flood

Excerpt from Gordon Pitts’ Unicorn in the Woods

When Brian Met Chris

In this excerpt from Unicorn in the Woods, acclaimed business journalist Gordon Pitts shares the story of how a billion dollars of value (USD) was created after a chance encounter between an entrepreneur and a tech innovator. Pitts’ book shows that economies outside major urban centres can develop and grow in a new economy, without relying exclusively on old-world, and increasingly unsustainable, resource extraction.

Chris Newton didn’t really expect much from the meeting. He would have been content to spend the day coding software in his tiny office along a dark corridor of the University of New Brunswick’s computer science building in Fredericton. But officials of the university—who, after all, were his employers—had insisted he go along to a gathering of alumni and potential investors in the hope of turning his little software idea into something commercial, something that might actually be sold.

He didn’t think he had a “product,” just a way of dealing with the denial-of-service attacks from mischief-makers that were wreaking havoc on the university’s ill-prepared computer networks in these early days of the internet and the wired university. Massive quantities of data would slam into the UNB network and shut it down, inciting a chorus of complaints. It created urgent calls for a cybersecurity tool that could give a real-time snapshot of the health and frailties of the system.

And that was what Newton was working on—this program he called Symon (short for System Monitor)—mostly at home at night as he wrote computer code well into the wee small hours.

But on that warm fall day in 2000, wearing shorts, sandals and a T-shirt, the 28-year-old part-time student and full-time UNB employee lugged his laptop up the hillside from his tiny office, through the cluster of UNB’s signature red brick buildings, toward the modernist Wu Conference Centre at the top of the hill. Below him lay the sleepy provincial capital with its 19th-century legislature, its sprawling frame mansions and the broad Saint John River as it curled downriver from its source in northern Maine.

A crowd of interested types—some local, some from as far away as Halifax—had gathered in a meeting room, creating the impression of a pilot for the future hit TV show Dragons’ Den. At his appointed time Newton flipped open his laptop screen and a chart appeared—a colour guide to the maze of computer networks that coursed through the university, where the emails went, where the downloads landed, where the trouble points were flaring up. There was a silence, and then a large dark-haired man moved closer to the front and fixed his attention on the screen, then started peppering Newton with a torrent of questions. What was this? Could it be sold? Who owned it? Can we talk?

Chris Newton was polite—he was the compactly built, baby-faced son of a police chief in the Miramichi, the rugged northeast New Brunswick region of salmon, forests and old mill sites. The only presenter under the age of 40, and the only non-academic, he projected boyish innocence and showed proper respect to people. He found the whole thing both unsettling and intriguing.

Newton finally managed to tear himself away and scrambled back down the hill to his office in the comfortable corridors of the UNB Computing Centre. But the big intensely energetic man would show up later, talking on about forming a company, creating a product and becoming an entrepreneur. Chris Newton didn’t know what an entrepreneur was—or a start-up or a business model or venture capital (VC). He just liked fixing stuff, figuring things out, solving problems for the people who employed him.

But his relentless pursuer was obsessed with all those entrepreneurial things. With the rangy build of an athlete, Brian Flood towered over Chris Newton. He was more than a decade older and 100 times more experienced in the ways of the world. Flood was like a man possessed, having spent the past four years preparing for this moment, when he could seize the chance for funding a technology breakthrough in his beleaguered home province.

He didn’t seem like a natural tech founder. He had been running a sports bar/restaurant down the road in Moncton, and later added another one in his hometown of Saint John—both cities about an hour or two’s drive from Fredericton. Then he got hooked on reading about this hot new thing called the internet. He embarked on a personal crash course to learn about this new pot of technology gold that had entranced everyone from tech titans Bill Gates and Steve Jobs to callow kids such as Mark Zuckerberg, still a student at a New England private school but about to burst on the world as a social-networking Harvard undergrad.

Flood was just back from one of his fact-finding expeditions to California’s Silicon Valley when he was invited to this showcase event by the sponsors at UNB. He had first met Newton in the “rubber room,” a session where the presenters were prepped for the show. Chris Newton seemed like the answer to his dreams—a whiff of game-changing innovation in the middle of his home province. As he chased Newton around the hillside university, he acted like a suddenly smitten suitor pursuing the reluctant target of his affections. He was not going to let this slip away. In the words of one friend, Brian Flood is the “weirdest, wackiest, hardest working, most tenacious son of a bitch.”

At one point in the courtship, Flood asked, almost as a throwaway line, what would IBM pay for this? Chris Newton pondered the thought: maybe the computer behemoth might cough up $25 a month for using the software or even as much as $500. Neither of them imagined that, a decade later, IBM would pay $600 million US for Chris’s little product and the company that grew out of it. And that by that time, Newton would have already gone on to cofound another company that he and his colleagues would have sold for about $330 million US. The bashful kid from the Miramichi would be New Brunswick’s billion-dollar man in value creation, putting him in the same rarified air as the Irvings, McCains, Olands, Sobeys and the other established business families whose names were synonymous with wealth, power and achievement on Canada’s East Coast.

–Excerpted from Unicorn in the Woods: How East Coast Geeks and Dreamers Are Changing the Game copyright ©2020 by Gordon Pitts. Reprinted by permission of Goose Lane Editions.

—Gordon Pitts is a former senior writer for the Globe and Mail’s Report on Business. He is the author of several books, including The Codfothers: Lessons from the Atlantic Business Elite and Stampede: The Rise of the West and Canada’s New Power Elite, winner of a National Business Book Award.

No comments:

Post a Comment