FORM 18-K

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

ANNUAL REPORT

Date of end of last fiscal year: March 31, 2002

SECURITIES REGISTERED*

| Time of Issue |

Amounts as to which registration Is effective |

Name of exchange on which registered |

||

|

N/A

|

N/A | N/A | ||

Name and address of person authorized to receive notices

HIS EXCELLENCY MICHAEL KERGIN

Copies to:

|

BILL MITCHELL

Director Financial Markets Division Department of Finance, Canada 20th Floor, East Tower L’Esplanade Laurier 140 O’Connor Street Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0G5 |

DAVID MURCHISON Consul Consulate General of Canada 1251 Avenue of the Americas New York, N.Y. 10020 |

ROBERT W. MULLEN, JR. Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy LLP 1 Chase Manhattan Plaza New York, N.Y. 10005 |

* The Registrant is filing this annual report on a voluntary basis.

The following chart shows the distribution of real gross domestic product (“GDP”) at basic prices (1997 constant dollars) in 2001, which is indicative of the structure of the economy.

DISTRIBUTION OF REAL GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT AT BASIC PRICES(1)

(1) GDP is a measure of production originating within the geographic boundaries of Canada, regardless of whether factors of production are Canadian or non-resident owned, whereas gross national product (“GNP”) measures the value of Canada’s total production of goods and services — that is, the earnings of all Canadian owned factors of production. Quantitatively, GDP is obtained from GNP by adding investment income paid to non-residents and deducting investment income received from non-residents. GDP at basic prices represents the value added by each of the factors of production and is equivalent to GDP at market prices less indirect taxes (net), plus other production taxes (net). Moreover, these differences in GDP measures explain any perceived discrepancies in GDP growth rates in this document.

(2) May not add to 100.0% due to rounding.

(3) The agriculture, forestry, fishing, hunting, mining and oil and gas extraction sectors include a service component.

The volume of industry and sector output in the following discussion provides “constant dollar” measures of the contribution of each industry to GDP at basic prices. The share of service-producing industries in real GDP was 68.7% in 2001 while the remaining 31.3% was attributed to goods-producing industries.

https://www3.forbes.com/business/forbes-rich-list-2020-canadian-wealthiest-billionaires-vue/

Canada’s Richest Billionaires 2020

Deputy Editors: Chase Peterson-Withorn, Jennifer Wang

Country Editors: Graham Button, Grace Chung, Russell Flannery, Naazneen Karmali

The richest people on Earth are not immune to the coronavirus. As the pandemic tightened its grip on Europe and America, global equity markets imploded, tanking many fortunes. When we finalized this list, Forbes counted 2,095 billionaires, 58 fewer than a year ago and 226 fewer than just 12 days earlier, when we initially calculated these net worths. Of the billionaires who remain, 51% are poorer than they were last year. In raw terms, the world’s billionaires are worth $8 trillion, down $700 billion from 2019.

METHODOLOGY

The Forbes World’s Billionaires list is a snapshot of wealth using stock prices and exchange rates from March 18, 2020. Some people become richer or poorer within days of publication. We list individuals rather than multigenerational families who share fortunes, though we include wealth belonging to a billionaire’s spouse and children if that person is the founder of the fortune. In some cases we list siblings or couples together if the ownership breakdown among them isn’t clear, but here an estimated net worth of $1 billion per person is needed to make the cut. We value a variety of assets, including private companies, real estate, art and more. We don’t pretend to know each billionaire’s private balance sheet (though some provide it). When documentation isn’t supplied or available, we discount fortunes.

Norm Betts/Bloomberg News

Norm Betts/Bloomberg News#1 David Thomson & family

Net Worth: $31.6 B

Age: 62

Source: Media

Industries: Media & Entertainment

David Thomson and his family control a media and publishing empire founded by his grandfather Roy Thomson. The family’s biggest holding: more than 320 million shares of Thomson Reuters, where Thomson serves as chairman. In 2018, Thomson Reuters announced it was selling a controlling stake in Refinitiv, a financial data provider, to Blackstone for $17 billion. The family also holds a stake in telecom giant Bell Canada and own the Toronto-based Globe and Mail newspaper.

GETTY

GETTY#2 Joseph Tsai

Net Worth: $10 B

Age: 56

Source: e-commerce

Industries: Technology

He is vice chairman and cofounder of Alibaba Group, and ranks as its second-largest individual shareholder after chairman Jack Ma. In 2018, he bought 49% of the Brooklyn Nets National Basketball Association team; the following year he purchased the remaining 51%. He holds two degrees from Yale University–an undergraduate degree in economics and East Asian studies and a law degree. Taiwan-born Tsai carries a Canadian passport.

David M. Benett/Dave Benett/Getty Images for Brasserie of Light

David M. Benett/Dave Benett/Getty Images for Brasserie of Light#3 Galen Weston & family

Net Worth: $7 B

Age: 79

Source: Retail

Industries: Fashion & Retail

Galen Weston is chairman emeritus of George Weston, the Canadian food and retail giant founded by his grandfather in 1882. After successfully running grocery and retail stores in Ireland, his father handed him the reins to the struggling Loblaws supermarket chain in 1972. He turned the company around, by lopping off underperforming stores and redesigning the rest. His son, Galen Jr., now runs both George Weston Ltd. and Loblaws, which acquired Canadian drugstore chain Shoppers for about $12 billion in July 2013. Weston also owns a group of upscale retailers: Canada’s Holt Renfrew, Ireland’s Brown Thomas and UK department store Selfridges.

Forbes

Forbes#4 David Cheriton

Net Worth: $5.5 B

Age: 69

Source: Google

Industries: Technology

“Professor Billionaire” David Cheriton, who teaches at Stanford University, made his fortune thanks to an early investment in Google. Cheriton and Andreas von Bechtolsheim (also now a billionaire) each invested $100,000 in Google when it was just getting started. The pair cofounded 3 companies: Arista Networks (IPO in 2014), Granite Systems (sold to Cisco in 1996) and Kealia (sold to Sun Microsystems in 2004). Cheriton resigned from Arista’s board in March 2014 and has been unloading his stock; he still owns nearly 10% through a trust for his children.

Forbes

Forbes#5 Huang Chulong

Net Worth: $5.1 B

Age: 61

Source: Real Estate

Industries: Real Estate

Huang Chulong chairs Galaxy Group, a privately held business based in the southern Chinese city of Shenzhen. Huang’s business interests span hotels, shopping malls, office leasing, parking-lot operation and real estate development.

Forbes

Forbes#6 Mark Scheinberg

Net Worth: $4.9 B

Age: 46

Source: Online Gaming

Industries: Gambling & Casinos

Mark Scheinberg cofounded PokerStars with his father, Isai, and built it into the world’s biggest online poker company before cashing out in 2014. Scheinberg, who owned 75% of Rational Group at the time, pocketed more than $3 billion from the sale. He helped launch PokerStars in 2001, at age 28, and benefited tremendously from the poker boom that soon swept the U.S. and the rest of world. Scheinberg is investing some of the proceeds in Madrid, where he is helping restore seven historic buildings for commercial and residential use. In 2018, Scheinberg bought a stake in the Ritz-Carlton Yacht Collection from majority owner, private equity firm Oaktree Capital. He also owns the One Hotel in Toronto, Canada, which is set to open its doors in late 2020.

Forbes

Forbes#7 James Irving

Net Worth: $4.5 B

Age: 92

Source: Diversified

Industries: Diversified

James Irving owns J.D. Irving, a conglomerate with more than two dozen companies in frozen foods, retail, shipbuilding, transportation and more. His timber and forestry operation, based in New Brunswick, has planted over a billion trees since 1957. His family’s fortune dates back to the 19th century, when his grandfather left Scotland and launched a general store and lumber and farming companies. His father added to the empire with oil operations in the 1920s; upon his 1992 death the three brothers James, Arthur and John split the assets. Irving Woodlands, a division of J.D. Irving, is the sixth-largest landowner in the U.S. with 1.25 million acres of land. Jim and Robert Irving, James Irving’s sons, are co-CEOs of the J. D. Irving empire, which also includes one of Canada’s biggest shipbuilders.

Forbes

Forbes#8 Jim Pattison

Net Worth: $4.3 B

Age: 91

Source: Diversified

Industries: Diversified

Jim Pattison oversees a sprawling group that operates 25 divisions including packaging, food and entertainment. Pattison’s first business was a GM dealership he bought in 1961. The Canadian billionaire also controls more than 40% of publicly-traded forest products company Canfor. His entertainment division includes Great Wolf Lodge, Guinness World Records and the Ripley’s Believe It Or Not! chain.

MARIA LAURA ANTONELLI/ZUMA PRESS/NEWSCOM

MARIA LAURA ANTONELLI/ZUMA PRESS/NEWSCOM#9 Emanuele (Lino) Saputo & family

Net Worth: $3.8 B

Age: 83

Source: Cheese

Industries: Food & Beverages

Emanuele (Lino) Saputo chaired his family’s eponymous dairy company from 1969 until his August 2017 retirement. His son, Lino Jr., who has served as president and CEO since 2004, succeeded him as chairman. The elder Saputo’s father, Giuseppe, founded the business in 1954 with $500 and a bicycle for deliveries after immigrating to Canada from Sicily. Lino grew the company in the following decades, taking it public in 1997; today its products are sold in more than 40 countries. The family also has a stake in Major League Soccer’s Montreal Impact.

Forbes

Forbes#10 Anthony von Mandl

Net Worth: $3.3 B

Source: Alcoholic Beverages

Industries: Food & Beverages

Anthony von Mandl created the ready-to-drink alcoholic beverages White Claw Hard Seltzer and Mike’s Hard Lemonade through his Mark Anthony Brands. von Mandl told Forbes his U.S. business is estimated to deliver close to $4 billion in revenue in 2020. He began his career in the Canadian wine business as an importer in the 1970s at age 22. He currently owns five wineries in Canada, including Mission Hill Winery in British Columbia’s Okanagan Valley. Through his company Mark Anthony Wine & Spirits, von Mandl is a leading figure of Canada’s alcohol importing and distribution sector.

CANADIAN PRESS

CANADIAN PRESS#11 (tie) Daryl Katz

Net Worth: $3.2 B

Age: 58

Source: Pharmacies

Industries: Diversified

Daryl Katz amassed a fortune in the pharmacy business, buying the Canadian rights to U.S. franchise Medicine Shoppe in 1991. A few years later he snatched up struggling Canadian drugstore chain Rexall, then expanded to the U.S. market. Katz, the son of a drug store owner, has since sold off all of his pharmacy operations, pivoting his Katz Group to real estate and entertainment. He has been co-developing a $2 billion, 25-acre complex in Edmonton’s downtown that will include offices, condos and retail, among others. Katz also owns his native city’s NHL team, the Edmonton Oilers.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES#11 (tie) Chip Wilson

Net Worth: $3.2 B

Age: 63

Source: Lululemon

Industries: Fashion & Retail

Dennis “Chip” Wilson, the founder and former CEO of Lululemon, opened Lululemon’s first store in Vancouver in 2000. He took the firm public in 2007 but resigned as chairman in 2013 and removed himself from the business completely in 2015. In 2013, Wilson blamed Lululemon’s too-sheer pants on women’s body types, causing an uproar among fans. Although Wilson has no management role in Lululemon, he remains its biggest individual shareholder. Wilson is currently involved in Hold It All, which has businesses in apparel, real estate and private equity. His investments include stakes in Finnish sporting goods firm Amer Sports and Chinese sports apparel company Anta Sports.

Forbes

Forbes#13 Alain Bouchard

Net Worth: $3.1 B

Age: 71

Source: Retail

Industries: Fashion & Retail

Alain Bouchard cofounded convenience store conglomerate Alimentation Couche-Tard with a single Quebec shop in 1980. As executive chairman, Bouchard still oversees the $59.1 billion (sales) company, which boasts more than 14,000 owned or franchised stores worldwide. Bouchard, who grew the business rapidly by snatching up competitors, retired as president and CEO in September 2014. In 2017, Couche-Tard acquired Texas-based CST Brands for $4.4 billion (including debt) and Minnesota-based Holiday Stationstores for $1.6 billion. Couche-Tard is reportedly pursuing the Australian fuel retailer Caltex Australia and is eyeing the cannabis industry.

DAVID FITZGERALD/SPORTSFILE VIA GETTY IMAGES

DAVID FITZGERALD/SPORTSFILE VIA GETTY IMAGES#14 Tobi Lutke

Net Worth: $3 B

Age: 39

Source: e-commerce

Industries: Technology

Tobias Lutke founded and runs Shopify, the Canadian e-commerce firm that helps companies set up and run online stores. He owns 6.7% of Shopify, which went public in 2015. Businesses that use Shopify technology for online sales include Kylie Cosmetics and shoe retailers Rothy’s and Allbirds. Lutke grew up in Germany, where he learned to code by age 12 and left school at 16 to enter a computer programming apprenticeship. Shopify had over $1 billion in 2018 revenue; it has 1 million businesses as customers from 175 countries.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES#15 Lawrence Stroll

Net Worth: $2.6 B

Age: 60

Source: Fashion Investments

Industries: Fashion & Retail

Lawrence Stroll masterminded Michael Kors’ hugely successful IPO in 2011 with business partner Silas Chou, a Hong Kong fashion tycoon. The bulk of Stroll’s fortune comes from selling his shares in the American fashion brand; he sold the last of his stake in 2014. In Aug. 2018, Stroll led a group of investors to buy Formula One racing team Force India for £90 million plus assumption of £15 million in debt. After leading a $235.6 million (£182 million) investment in car company Aston Martin in early 2020, Stroll will become executive chairman. His 20-year-old son, Lance Stroll, one of the youngest members to compete in Formula One, is joining Force India in 2019. Stroll collects vintage Ferraris, one of which he purchased for a record-breaking $27.5 million in 2013.

BOB GAGLARDI

BOB GAGLARDI#16 (tie) Bob Gaglardi

Net Worth: $2.5 B

Age: 79

Source: Hotels

Industries: Real Estate

Bob Gaglardi founded Northland Properties, which has interests in hotels, restaurants, sports, and construction. Gaglardi launched the business in 1963 with a $5,000 loan, opening his first Sandman Inn hotel four years later in British Columbia. He continued to put up Sandman Inns throughout Canada, plus expanded into real estate and restaurants. In 2011 he and his son, Tom, purchased the then-bankrupt Dallas Stars NHL team in a $240 million deal.

Forbes

Forbes#16 (tie) Arthur Irving

Net Worth: $2.5 B

Age: 90

Source: Oil

Industries: Energy

New Brunswick native Arthur Irving owns 100% of Irving Oil, which operates gas stations and oil refineries, through the Arthur Irving Family Trust. Arthur is a third-generation member of a Canadian dynasty. His grandfather, James Dergavel Irving, started the family business in the late 1800s. His dad Kenneth Colin (K.C) Irving added oil operations in 1920s; Arthur and his 2 brothers reportedly divided up the empire after KC’s death in 1992. Arthur’s brother James Irving, also a billionaire, took over a conglomerate that spans shipbuilding to forestry. A third Irving brother, John (known as Jack), headed the family’s construction operations and owned part of Irving Oil. He passed away in 2010. In 2018, The Arthur Irving Family Trust bought out Jack Irving family’s stake to assume 100% ownership of Irving Oil.

Forbes

Forbes#18 Jean Coutu & family

Net Worth: $2.4 B

Age: 92

Source: Drugstores

Industries: Fashion & Retail

The billionaire in the white lab coat, Jean Coutu founded the Canadian drugstore chain that bears his name. In October 2017 Coutu agreed to sell his publicly-traded company to supermarket giant Metro for $4.5 billion in cash and stock. Son of a pediatrician, he opened his first pharmacy in 1969, merging low prices on wide-ranging products with customer service and extended hours. Coutu, who was chief executive until 2002 and then again from 2005 to 2007, grew The Jean Coutu Group by acquiring many of his competitors. The company was once a leading shareholder of U.S. drug store operator Rite Aid but sold the last of its stake in 2013.

Forbes

Forbes#19 Charles Bronfman

Net Worth: $2.3 B

Age: 88

Source: Liquor

Industries: Food & Beverages

Charles Bronfman is long removed from the 2000 deal in which he and nephew Edgar Jr. sold their family’s Seagram spirits to Vivendi for $34 billion. His father Samuel Bronfman, a Russian immigrant to Canada, started a small distillery in 1924 and eventually bought out competitor Seagram. Since the sale, Charles, who once co-chaired Seagram, has turned toward philanthropy, authoring two books on the matter and signing The Giving Pledge. Bronfman has given away or pledged at least $350 million, mostly toward promotion of Canadian culture and the Jewish community’s connection to Israel. Bronfman’s son, Stephen, now runs Claridge, the Montreal-based private investment firm that Charles founded in 1987.

Forbes

Forbes#20 (tie) Mitchell Goldhar

Net Worth: $2.2 B

Age: 58

Source: Real Estate

Industries: Real Estate

Mitchell Goldhar founded real estate firm SmartCentres in the early 1990s, then developed more than 265 shopping centers in the ensuing two decades. In May 2015, he sold most of SmartCentre’s assets to SmartREIT (formerly Calloway REIT), for about $880 million in shares, cash and assumed debt. Goldhar, who chairs SmartREIT, also owns various developments across Canada through his private company Penguin Investments. This includes a stake, along with SmartREIT, in the Vaughan Metropolitan Centre, a 100-acre master planned development north of Toronto. Goldhar owns Israeli soccer team Maccabi Tel Aviv FC, which won the Israeli club league in 2019. He plays squash, tennis and hockey.

Forbes

Forbes#20 (tie) Barry Zekelman

Net Worth: $2.2 B

Age: 53

Source: Steel

Industries: Manufacturing

Barry Zekelman took over his family’s steel business at age 19 and has since grown it into one of North America’s largest steel pipe and tube makers. He sold the company to the Carlyle Group in 2006 for some $1.2 billion, but continued to help run it. He and his family bought it back in 2011. Today Barry and his two brothers, Clayton and Alan Zekelman, split 100% ownership of the $2.8 billion (revenues) firm, now named Zekelman Industries. He made headlines when he was captured on a secret recording of a 2018 Trump donor dinner, bending the president’s ear about the steel business. One of Zekelman Industries’ subsidiaries, Atlas Tube, is producing steel for the stretches of the Mexican border wall going up in Arizona.

Forbes

Forbes#22 Carlo Fidani

Net Worth: $2.1 B

Age: 65

Source: Real Estate

Industries: Real Estate

Carlo Fidani runs Orlando Corp., the Toronto-area real estate company he took over following his father’s death in 2000. The company has interests in construction and development, plus manages some 44 million square feet of industrial, office and commercial space. His grandfather founded the business as Fidani and Sons in 1948; Carlo took over in 2000 following his father’s death. Fidani was made a Member of the Order of Canada in September 2018, an honor recognizing his achievements and service to the country.

Tannis Toohey/Toronto Star via Getty Images

Tannis Toohey/Toronto Star via Getty Images#23 Michael Lee-Chin

Net Worth: $2 B

Age: 69

Source: Mutual Funds

Industries: Finance & Investments

Michael Lee-Chin made a fortune investing in financial companies like National Commercial Bank Jamaica and AIC Limited. The native of Jamaica acquired AIC in 1987, when it had less than $1 million in assets under management. Under Lee-Chin, the Canada-based wealth management and mutual fund business managed more than $10 billion in assets by 2002. But the firm was hit hard by the 2008 recession, and Lee-Chin sold AIC to Canadian financial services group Manulife in 2009 for an undisclosed price. He managed to hold onto a valuable 65% stake in National Commercial Bank Jamaica, which now makes up the majority of his wealth.

© 2018 BLOOMBERG FINANCE LP

© 2018 BLOOMBERG FINANCE LP#24 Bruce Flatt

Net Worth: $1.9 B

Age: 54

Source: Money Management

Industries: Finance & Investments

Bruce Flatt is one of the biggest and best investors you’ve likely never heard of. Flatt runs Brookfield Asset Management, the $540 billion (assets) alternative manager with real estate, infrastructure and private equity operations. A Winnipeg native, he joined an accounting firm out of college, then took a job at Canadian conglomerate Brascan, which soon nearly collapsed. He helped revive Brascan through a series of savvy real estate deals and became CEO in 2002, refashioning the firm into Brookfield Asset Management. His winning deals include buying Olympia & York in 1996 and London’s Canary Wharf in 2015, and recapitalizing General Growth Properties in 2010.

Forbes

Forbes#25 (tie) Peter Gilgan

Net Worth: $1.8 B

Age: 69

Source: Homebuilding

Industries: Construction & Engineering

Peter Gilgan has built houses for some 90,000 homeowners since founding Mattamy Homes in 1978. Gilgan, who grew up as one of seven children in a middle class family, worked as an accountant before going into building. Inspired by the New Urbanism movement, he set out to construct suburban dwellings that broke from the bland and impersonal developments. Mattamy (named after the two oldest of his eight children, Matt and Amy) began designing and building planned communities from the ground up in 1986. Gilgan remains CEO of the $3 billion (revenues) business.

Asbed.com/Lumisculpt

Asbed.com/Lumisculpt#25 (tie) Robert Miller

Net Worth: $1.8 B

Age: 74

Source: Electronics Components

Industries: Technology

Canadian Robert Miller cofounded electronics distributor Future Electronics in 1968. In 1976, he bought out his partner for $500,000; now the Quebec-based company is one of the world’s largest electronics distributors. Future Electronics has a reported $5 billion in revenues from operations in 44 countries. Its products include adapter boards for LED screens, microcontrollers and LED lighting.

JAMEL TOPPIN FOR FORBES

JAMEL TOPPIN FOR FORBES#25 (tie) Peter Szulczewski

Net Worth: $1.8 B

Age: 38

Source: e-commerce

Industries: Technology

Peter Szulczewski owns about 18% of e-commerce marketplace Wish, which connects shoppers with merchants who are mostly in China. In August 2019, Wish raised a reported $300 million round that valued the company at over $11 billion. Szulczewski grew up in an apartment block in Tarchomin, a district of Warsaw, then immigrated with his family to Canada at age 11. The computer science grad joined Google, where he helped build software that helps advertisers target people’s searches. He quit Google in 2009 to start his own software company, ContextLogic, which looked at a person’s browsing to predict their interests. In 2011 Szulczewski and college friend Danny Zhang re-launched the company as Wish.

#28 Garrett Camp

Net Worth: $1.7 B

Age: 41

Source: Uber

Industries: Technology

Uber chairman Garrett Camp cofounded the ride-hailing startup with Travis Kalanick in 2009. The Uber mobile phone app lets users request a ride and a driver-contractor is routed to pick them up — with Uber getting a cut of the fare. Camp owns about 4% of Uber, which listed its shares on the New York Stock Exchange on May 10, 2019. Before Uber, Garrett Camp founded web discovery tool StumbleUpon, which he sold to eBay in 2007 for $75 million.

JUDY SIEGEL-ITZKOVICH/THE JERUSALEM POST

JUDY SIEGEL-ITZKOVICH/THE JERUSALEM POST#29 (tie) Marcel Adams & family

Net Worth: $1.5 B

Age: 99

Source: Real Estate

Industries: Real Estate

One of Canada’s most prolific real estate investors, Marcel Adams founded Iberville Developments in 1958. Iberville owns and manages nearly 8 million square feet across some 100 shopping centers, office spaces, industrial properties and residential assets. Born in Romania under the last name “Abramovich,” Adams survived Holocaust labor camps during World War II before coming to Canada. He got his start working in the leather industry, but began investing in local real estate by the mid 1950s. His son, Sylvan Adams, a “Giving Pledge” signatory who now lives in Israel, has since taken over the business.

#29 (tie) Jacques D’Amours

Net Worth: $1.5 B

Age: 63

Source: Retail

Industries: Fashion & Retail

Jacques D’Amours co-founded Canadian convenience store conglomerate Alimentation Couche-Tard in 1980. He retired as VP of administration in 2014, but remains on the company’s board and is its second-largest shareholder. Couche-Tard has ballooned by snatching up competitors, including Minnesota-based Holiday Stationstores for $1.6 billion in December 2017. The company now boasts annual sales of $59 billion and more than 14,000 owned or franchised stores worldwide.

#29 (tie) Stephen Jarislowsky

Net Worth: $1.5 B

Age: 94

Source: Money Management

Industries: Finance & Investments

Stephen Jarislowsky made the bulk of his fortune at the helm of Jarislowsky Fraser, the investment management firm he founded in 1955. He stepped down as CEO in 2012 but remains chairman emeritus of the company and president of the Jarislowsky Foundation. Canadian bank Scotiabank bought Jarislowsky Fraser for about $750 million in stock and cash in April 2018. He owns a sizable art collection that is largely comprised of Canadian art, but also includes Chinese jade and French impressionism. His foundation has endowed over $220 million and has established 40 university chairs across Canada.

Forbes

Forbes#32 (tie) Hal Jackman

Net Worth: $1.4 B

Age: 87

Source: Insurance, Investments

Industries: Finance & Investments

Hal Jackman and his family are the largest shareholders of E-L Financial Corporation, a Toronto investment and insurance holding company. His father, former Parliament member Harry Jackman, built a financial services empire, which Hal continued to expand over his decades at the helm. His son, Duncan, now runs the business as chief executive officer, president and chairman of E-L Financial. Jackman followed in his father’s footsteps into politics, serving as the 25th lieutenant governor of Ontario from 1991 to 1997.

Forbes

Forbes#32 (tie) Serge Godin

Net Worth: $1.4 B

Age: 70

Source: Information Technology

Industries: Technology

Serge Godin is chairman of Canadian tech firm CGI Group, which he founded in 1976 at age 26. One of nine children, Godin started working for his father (who had just a fifth-grade education) at the family’s sawmill at age 12. He studied computer science and got an MBA from Quebec’s Université Laval, then worked in consulting before using $5,000 in savings to start CGI. Godin serves as chairman of the $9.3 billion (revenue) company; he was president and CEO until 2006. He has overseen more than 70 acquisitions, including the 1998 purchase of Bell Sygma, which nearly doubled the size of the company at the time.

Forbes

Forbes#32 (tie) Pierre Karl Péladeau

Net Worth: $1.4 B

Age: 58

Source: Media

Industries: Media & Entertainment

The son of Quebecor’s founder, Pierre Karl Péladeau is the largest individual shareholder in the media company, which prints Le Journal de Montréal. Péladeau has spent 16 years as the company’s CEO–taking a three year break between 2014 and 2017. In 2015, he won and led the separatist Parti Québécois for nearly a year, before resigning in May 2016. In February 2017, he returned as CEO of a very healthy Quebecor, as shares rose 70% during his political stint.

![]()

#32 (tie) Clayton Zekelman

Net Worth: $1.4 B

Age: 51

Source: Steel

Industries: Manufacturing

Clayton Zekelman owns a stake in his family’s steel business, Zekelman Industries. The $2.8 billion (revenues) company is one of North America’s largest steel pipe and tube makers. Clayton and his brothers, fellow billionaires Barry Zekelman and Alan Zekelman, split 100% ownership of Zekelman Industries. They sold the company to the Carlyle Group in 2006 for some $1.2 billion, but bought the business back in 2011. One of Zekelman Industries’ subsidiaries, Atlas Tube, is producing steel for the stretches of the Mexican border wall going up in Arizona. He also owns two telecoms companies in Ontario.

Forbes

Forbes#36 (tie) Jack Cockwell

Net Worth: $1.3 B

Age: 79

Source: Real Estate, Private Equity

Industries: Finance & Investments

A South African native and trained accountant, Jack Cockwell is a famed dealmaker in Canada. From the 1970s through the early 1990s he built the Bronfmans’ Edper conglomerate, acquiring massive holdings in real estate, forestry and mining. Now known as Brookfield Asset Management, one of the world’s biggest money managers, he handed the reins to fellow billionaire Bruce Flatt in 2002. His wealth comes from a large holding in Brookfield shares, much of it in a partnership shared with other board directors and management. Cockwell is a member of Ryerson University’s board of governors and governor of the Royal Ontario Museum.

Forbes

Forbes#36 (tie) Terence (Terry) Matthews

Net Worth: $1.3 B

Age: 77

Source: Telecom

Industries: Telecom

A dual-UK Canadian citizen, Terence (Terry) Matthews made his fortune with telecom firms Mitel and Newbridge Networks. In December 2018, he left his Chairman role at Mitel, the company he co-founded with Michael Cowpland, after it was acquired for $2 billion. In 1986, Matthews founded data networking business Newbridge Networks before selling it to Alcatel in 2000 for $7.1 billion. He claims to have funded or founded more than 100 companies, many through his Ottawa-based investment firm Wesley Clover. A resident of Canada, his UK property portfolio includes Celtic Manor Resort, which hosted the 2010 Ryder Cup and 2014 NATO Summit.

James MacDonald/Bloomberg

James MacDonald/Bloomberg#36 (tie) Stephen Smith

Net Worth: $1.3 B

Age: 68

Source: Finance & Investments

Industries: Finance & Investments

Stephen Smith is the founder, chairman and CEO of Canadian mortgage lender First National Financial. Smith launched the company in 1988, just four years after being personally bankrupt, and took it public in 2012. He also owns about half of Canada Guaranty Mortgage Insurance Company and a stake in publicly-traded Canadian bank Equitable Group. In 2018, he bought half of Walmart Canada Bank from Walmart and put up over $110 million to start the private equity fund Peloton. In 2015 he donated $50 million the Queens University, where the business school is named after him.

#39 (tie) Aldo Bensadoun

Net Worth: $1.1 B

Age: 81

Source: Shoes

Industries: Fashion & Retail

Aldo Bensadoun is the founder of Canadian retailer ALDO, best known for its footwear and accessories. The son of a shoe merchant and grandson of a cobbler, Bensadoun was born in Morocco and spent most of his childhood in France. Upon moving to Montreal for college, he opened ALDO as a concession within a chain of popular fashion boutiques in 1972. His son, David, who is now the CEO, joined the company in 1996 and became the fourth generation of his family to work in the shoe business. ALDO pulled in an estimated $1.5 billion in sales in 2019 and has more than 3,000 stores across the world.

#39 (tie) Guy Laliberté

Net Worth: $1.1 B

Age: 60

Source: Cirque du Soleil

Industries: Media & Entertainment

In 1984, Guy Laliberté, a former street performer, cofounded Cirque du Soleil, which would become one of the world’s biggest entertainment companies. His empire began with a show, funded by $1 million from the Canadian government, put on for the 450th anniversary of the discovery of Canada. The celebration went global, and the shows have been performed for more than 180 million spectators across more than 400 cities on six continents. He sold much of his 90% stake to U.S. private equity firm TPG Capital and Chinese investment group Fosun in 2015, but kept 10% of the company. In 2017, he founded Lune Rouge, which develops and invests in projects in arts, technology and entertainment. Laliberté was briefly held in custody in Tahiti for growing cannabis at his French Polynesian residence in November 2019.

#39 (tie) Mark Leonard & family

Net Worth: $1.1 B

Age: 63

Source: Software

Industries: Technology

Mark Leonard is chairman of Canadian tech company Constellation Software, which he founded in 1995. Constellation Software, also known as CSI, acquires, manages and builds software businesses. In 2019, the firm acquired nearly 100 tech companies. Constellation Software, also known as CSI, acquires, manages and builds software businesses. In 2018, the firm acquired 8 tech companies. After getting his MBA from the University of Western Ontario, Leonard worked in venture capital for 11 years.

#39 (tie) Brandt Louie

Net Worth: $1.1 B

Age: 76

Source: Drugstores

Industries: Food & Beverage

Louie presides over grocery retailer H.Y. Louie and drug store chain London Drugs. His Vancouver-based holding company H.Y. Louie is the third-largest private firm in British Columbia, with an estimated $4.2 billion in revenue. His grandfather, Hok Yat Louie, immigrated to Vancouver from China in 1896 and worked as a farm laborer. Hok Yat eventually saved enough money to open a small general store in the city’s Chinatown in 1903. Louie joined the family business in 1972 and became president in 1987.

#39 (tie) Alan Zekelman

Net Worth: $1.1 B

Age: 57

Source: Steel

Industries: Manufacturing

Alan Zekelman owns a stake in his family’s steel business, Zekelman Industries. The $2.8 billion (revenues) company is one of North America’s largest steel pipe and tube makers. Alan and his brothers, fellow billionaires Barry Zekelman and Clayton Zekelman, split 100% ownership of Zekelman Industries. They sold the company to the Carlyle Group in 2006 for some $1.2 billion, but bought the business back in 2011. One of Zekelman Industries’ subsidiaries, Atlas Tube, is producing steel for the stretches of the Mexican border wall going up in Arizona.

Forbes

Forbes#44 Gerald Schwartz

Net Worth: $1 B

Age: 78

Source: Finance

Industries: Finance & Investments

Gerald Schwartz runs Onex, one of Canada’s largest private equity firms. He got his start working with buyout legends Jerome Kohlberg, Henry Kravis and George Roberts at Bear Stearns in the 1970s. The Americans left to start KKR in 1976; Schwartz went home to Canada and cofounded the media company CanWest in 1977. In 1984 he started Onex, which has quietly outperformed many of the vaunted American private equity shops. Today the firm boasts $38 billion in assets, which Schwartz manages as chairman and CEO.

FORM 18-K

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

ANNUAL REPORT

Date of end of last fiscal year: March 31, 2002

SECURITIES REGISTERED*

| Time of Issue |

Amounts as to which registration Is effective |

Name of exchange on which registered |

||

|

N/A

|

N/A | N/A | ||

Name and address of person authorized to receive notices

HIS EXCELLENCY MICHAEL KERGIN

Copies to:

|

BILL MITCHELL

Director Financial Markets Division Department of Finance, Canada 20th Floor, East Tower L’Esplanade Laurier 140 O’Connor Street Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0G5 |

DAVID MURCHISON Consul Consulate General of Canada 1251 Avenue of the Americas New York, N.Y. 10020 |

ROBERT W. MULLEN, JR. Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy LLP 1 Chase Manhattan Plaza New York, N.Y. 10005 |

* The Registrant is filing this annual report on a voluntary basis.

Table of Contents

The information set forth below is to be furnished:

| 1. | In respect of each issue of securities of the registrant registered, a brief statement as to: |

| (a) | The general effect of any material modifications, not previously reported, of the rights of the holders of such securities. |

No such modifications.

| (b) | The title and the material provisions of any law, decree or administrative action, not previously reported, by reason of which the security is not being serviced in accordance with the terms hereof. |

No such provisions.

| (c) | The circumstances of any other failure, not previously reported, to pay principal, interest, or any sinking fund or amortization installment. |

No such failure.

| 2. | A statement as of the close of the last fiscal year of the registrant giving the total outstanding of: |

| (a) | Internal funded debt of the registrant. (Total to be stated in the currency of the registrant. If any internal funded debt is payable in a foreign currency, it should not be included under this paragraph (a) but under paragraph (b) of this item). |

Reference is made to pages 25-27 of Exhibit D.

| (b) | External funded debt of the registrant. (Totals to be stated in the respective currencies in which payable). No statement need be furnished as to inter-governmental debt. |

Reference is made to pages 25-27 of Exhibit D.

| 3. | A statement giving the title, date of issue, date of maturity, interest rate and amount outstanding, together with the currency or currencies in which payable, of each issue of funded debt of the registrant outstanding as of the close of the last fiscal year of the registrant. |

Reference is made to pages 34-47 of Exhibit D.

| 4. (a) | As to each issue of securities of the registrant which is registered, there should be furnished a breakdown of the total amount outstanding, as shown in Item 3, into the following: |

| (1) | Total amount held by or for the account of the registrant. |

As at December 1, 2002, the registrant held a de minimis amount.

| (2) | Total estimated amount held by nationals of the registrant (or if registrant is other than a national government, by the nationals of its national government); this estimate need be furnished only if it is practicable to do so. |

Not practicable to furnish.

| (3) | Total amount otherwise outstanding. |

Not applicable.

| (b) | If a substantial amount is set forth in answer to paragraph (a)(1) above, describe briefly the method employed by the registrant to reacquire such securities. |

Not applicable.

| 5. | A statement as of the close of the last fiscal year of the registrant giving the estimated total of: |

| (a) | Internal floating indebtedness of the registrant. (Total to be stated in the currency of the registrant). |

Reference is made to pages 25-27 of Exhibit D.

| (b) | External floating indebtedness of the registrant. (Total to be stated in the respective currencies in which payable). |

Reference is made to pages 25-27 of Exhibit D.

Table of Contents

| 6. | Statements of the receipts, classified by source, and of the expenditures, classified by purpose, of the registrant for each fiscal year of the registrant ended since the close of the latest fiscal year for which such information was previously reported. These statements should be so itemized as to be reasonably informative and should cover both ordinary and extraordinary receipts and expenditures; there should be indicated separately, if practicable, the amount of receipts pledged or otherwise specifically allocated to any issue registered, indicating the issue. |

Reference is made to pages 18-24 of Exhibit D.

| 7. (a) | If any foreign exchange control, not previously reported, has been established by the registrant (or if the registrant is other than a national government, by its national government), briefly describe such foreign exchange control. |

No foreign exchange controls have been established by the registrant.

| (b) | If any foreign exchange control previously reported has been discontinued or materially modified, briefly describe the effect of any such action, not previously reported. |

Not applicable.

| 8. | Brief statements as of a date reasonably close to the date of the filing of this report (indicating such date) in respect of the note issue and gold reserves of the central bank of issue of the registrant, and of any further gold stocks held by the registrant. |

Reference is made to page 17 of Exhibit D.

| 9. | Statements of imports and exports of merchandise for each year ended since the close of the latest year for which such information was previously reported. Such statements should be reasonably itemized so far as practicable as to commodities and as to countries. They should be set forth in terms of value and of weight or quantity; if statistics have been established only in terms of value, such will suffice. |

Reference is made to pages 12-14 of Exhibit D.

| 10. | The balances of international payments of the registrant for each year ended since the close of the latest year for which such information was previously reported. The statements of such balances should conform, if possible, to the nomenclature and form used in the “Statistical Handbook of the League of Nations.” (These statements need be furnished only if the registrant has published balances of International payments.) |

Reference is made to pages 15-16 of Exhibit D.

On March 12, 1996, Canada established a program for the offering, from time to time, of its Canada Notes due nine months or more from date of issue (“Canada Notes”). During the period from December 1, 2001 through November 30, 2002, Canada did not file with the United States Securities and Exchange Commission any pricing supplements relating to the sale of Canada Notes. Consequently, the portion of Canada Notes sold or to be sold during that period in the United States or in circumstances where registration of the Canada Notes is required through November 30, 2002 was U.S.$0.

Cautionary statement for purposes of the “safe harbor” provisions of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995.

This annual report, including the exhibits hereto, contains various forward-looking statements and information that are based on Canada’s belief as well as assumptions made by and information currently available to Canada. When used in this document, the words “anticipate”, “estimate”, “project”, “expect”, “should” and similar expressions are intended to identify forward-looking statements. Such statements are subject to certain risks, uncertainties and assumptions. Should one or more of these risks or uncertainties materialize, or should underlying assumptions prove incorrect, actual results may vary materially from those anticipated, estimated or projected. Among the key factors that have or will have a direct bearing on Canada are the world-wide economy in general and the actual economic, social and political conditions in or affecting Canada.

Table of Contents

This annual report comprises:

| (a) | Pages numbered 1 to 5 consecutively. | |

| (b) | The following exhibits: |

|

Exhibit A:

|

None | |

|

Exhibit B:

|

None | |

|

Exhibit C-1:

|

Copy of the 2001 Budget of Canada (incorporated by reference from Exhibit C-4 to Canada’s Amendment No. 3 to Form 18-K for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2000) | |

|

Exhibit C-2:

|

Copy of the Economic and Fiscal Update October 30, 2002, Department of Finance, Canada (incorporated by reference from Exhibit C-2 to Canada’s Amendment No. 1 to Form 18-K for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2001 on Form 18-K/A dated November 1, 2002) | |

|

Exhibit D:

|

Current Canada Description | |

|

Exhibit E:

|

Consent of Deputy Minister of Finance |

This annual report is filed subject to the instructions for Form 18-K for Foreign Governments and Political Subdivisions Thereof.

Table of Contents

SIGNATURE

Pursuant to the requirements of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, the registrant has duly caused this annual report to be signed on its behalf by the undersigned, thereunto duly authorized, at Ottawa, Canada, on the 20th day of December, 2002.

| CANADA | ||||

| By: | /s/ Rob Stewart | |||

| Rob Stewart | ||||

| Senior Chief | ||||

| Financial Markets Division | ||||

| Financial Sector Policy Branch | ||||

| Department of Finance, Canada | ||||

Table of Contents

EXHIBIT INDEX

| Exhibit No. | ||

|

Exhibit A:

|

None | |

|

Exhibit B:

|

None | |

|

Exhibit C-1:

|

Copy of the 2001 Budget of Canada (incorporated by reference from Exhibit C-4 to Canada’s Amendment No. 3 to Form 18-K for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2000) | |

|

Exhibit C-2:

|

Copy of the Economic and Fiscal Update October 30, 2002, Department of Finance, Canada (incorporated by reference from Exhibit C-2 to Canada’s Amendment No. 1 to Form 18-K for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2001 on Form 18-K/A dated November 1, 2002) | |

|

Exhibit D:

|

Current Canada Description | |

|

Exhibit E:

|

Consent of Deputy Minister of Finance |

Table of Contents

DESCRIPTION OF CANADA

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| Page | ||

|

General Information

|

3 | |

|

The Canadian Economy

|

6 | |

|

External Trade

|

12 | |

|

Balance of Payments

|

15 | |

|

Foreign Exchange and International Reserves

|

17 | |

|

Government Finances

|

18 | |

|

Debt Record

|

28 | |

|

Monetary and Banking System

|

29 | |

|

Tables and Supplementary Information

|

34 |

Unless otherwise indicated, dollar amounts hereafter in this document are expressed in Canadian dollars. On December 16, 2002 the noon buying rate in New York City payable in Canadian dollars (“$”), as reported by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, was $1.00 = $0.6399 United States dollars (“U.S.$”). See “Foreign Exchange and International Reserves”.

Table of Contents

2

Table of Contents

The information contained herein has been reviewed by Kevin G. Lynch, Deputy Minister of Finance, Canada and is included herein on his authority. Certain information contained in this Exhibit has been extracted or compiled from public official documents of Canada, which include statistical data subject to revision. Canada is sometimes referred to as the “Government of Canada” or the “Government” in this Exhibit.

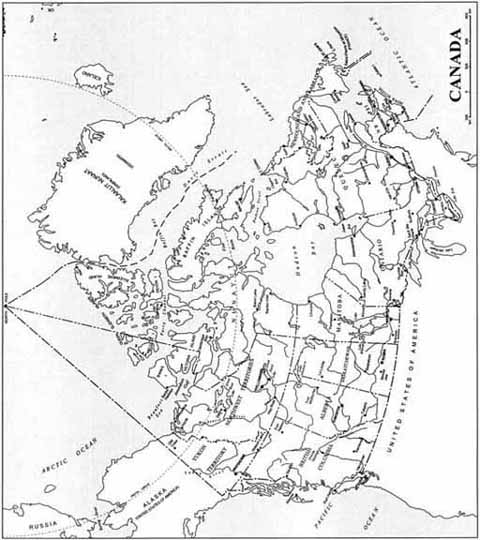

CANADA

Area and Population

Canada is the second largest country in the world, with an area of 9,984,670 square kilometers of which about 891,163 square kilometers are covered by fresh water. The occupied farm land is about 7% and the productive forest land is about 24% of the total area. The population on July 1, 2002 was estimated to be 31.4 million. Approximately 64% of Canada’s population lives in metropolitan areas of which Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver are the largest. Most of Canada’s population lives within 325 kilometers of the United States border.

Form of Government

Canada is a federal state composed of ten provinces and three territories. In 1867, the United Kingdom Parliament adopted the British North America Act, which established the Canadian federation comprised of, at that time, the Provinces of Ontario, Québec, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. Since then, six additional provinces (Manitoba, British Columbia, Prince Edward Island, Saskatchewan, Alberta and Newfoundland and Labrador), along with the Yukon Territory, the Northwest Territories and the new territory of Nunavut (which was carved out of the Northwest Territories on April 1, 1999), have become parts of Canada.

The British North America Act (which has been renamed the Constitution Act, 1867) gave the Parliament of Canada legislative power in relation to a number of matters including all matters not assigned exclusively to the legislatures of the provinces. These powers now include matters such as defense, the raising of money by any mode or system of taxation, the regulation of trade and commerce, the public debt, money and banking, interest, bills of exchange and promissory notes, navigation and shipping, extra-provincial transportation, aerial navigation and, with some exceptions, telecommunications. The provincial legislatures have exclusive jurisdiction in such areas as education, municipal institutions, property and civil rights, administration of justice, direct taxation for provincial purposes and other matters of purely provincial or local concern.

The executive power of the federal Government is vested in the Queen, represented by the Governor General, whose powers are exercised on the advice of the federal Cabinet, which is responsible to the House of Commons. The legislative branch at the federal level, Parliament, consists of the Crown, the Senate and the House of Commons. The Senate has 105 seats. There are 24 seats each for the Maritime Provinces, Québec, Ontario and Western Canada, 6 for Newfoundland and 1 each for the three territories. Senators are appointed by the Governor General on the advice of the federal Cabinet and hold office until age 75. The House of Commons has 301 members, elected by voters in single-member constituencies. The leader of the political party that gains the most seats in each general election is usually invited by the Governor General to be Prime Minister and to form the Government. The Prime Minister selects the members of the federal Cabinet from among the members of the House of Commons and the Senate (in practice almost entirely from the former). The House of Commons is elected for a period of five years, subject to earlier dissolution upon the recommendation of the Prime Minister or because of the Government’s defeat in the House of Commons on a vote of no confidence.

The most recent general election was held on November 27, 2000. As a result of that election the Liberal Party forms the Government. The distribution of seats in the House of Commons is as follows: the Liberal Party has 169 seats, the Canadian Alliance Party has 63 seats, the Bloc Québécois has 35 seats, the New Democratic Party has 14 seats and the Progressive Conservative Party has 14 seats. There are 3 independent members and 3 vacant seats.

The executive power in each province is vested in the Lieutenant Governor, appointed by the Governor General on the advice of the federal Cabinet. The Lieutenant Governor’s powers are exercised on the advice of the provincial cabinet, which is responsible to the legislative assembly. Each provincial legislature is composed of a Lieutenant Governor and a legislative assembly made up of members elected for a period of five years. The practice of selecting the provincial premier and the provincial cabinet in each province follows that described for the federal level, as does dissolution of a legislature.

3

Table of Contents

The judicial branch of government in Canada is composed of an integrated set of courts created by federal and provincial law. At the federal level there are two principal courts, the Supreme Court of Canada which is the highest appeal court in Canada and the Federal Court of Canada which, among other things, deals with federal revenue laws and claims involving the Government. Judges of the two federally constituted courts and those of the provincial superior and county courts are appointed by the Governor General on the advice of the federal Cabinet and hold office during good behavior until age 70 or 75. Judges of the magistrates courts (commonly now known as provincial courts) are appointed by the provincial government and usually hold office until age 65 or 70.

Constitutional Reform

In April 1982, Her Majesty the Queen proclaimed the Constitution Act, 1982, terminating British legislative jurisdiction over Canada’s Constitution. The Constitution Act, 1982 provides that Canada’s Constitution may be amended pursuant to an amending formula contained therein and contains the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, including the linguistic rights of Canada’s two major language groups.

The government of Québec did not sign the constitutional agreement which led to the repatriation of the Canadian Constitution and the proclamation of the Constitution Act, 1982. Although Québec is legally bound by the Constitution Act, 1982, the government of Québec set out five conditions for accepting the legal legitimacy of the Act. Discussions on those principles led on April 30, 1987 at Meech Lake to a unanimous agreement by First Ministers on principles respecting each of Québec’s conditions.

A constitutional resolution to give effect to the Meech Lake Accord was adopted by Parliament and eight provinces before the deadline for ratification on June 23, 1990. In the absence of ratification by Newfoundland and Manitoba, the amendment was not adopted. In the wake of this event, the most extensive series of public consultations on constitutional matters ever to occur in Canada began through the work of both provincial and federal commissions and committees, among other things. Recommendations produced by this process were then assessed by a series of multilateral negotiations involving the federal, provincial and territorial governments and four national Aboriginal organizations, held from April to July 1992. Agreement was reached on a wide range of constitutional issues through the multilateral process which led to a First Ministers’ Conference held in Charlottetown in August 1992.

The Charlottetown Accord was an extensive package of reforms agreed upon by the federal, provincial and territorial governments and the four Aboriginal organizations. On October 26, 1992 Canadians were asked in a referendum if they agreed that the Constitution of Canada should be renewed on the basis of the Charlottetown agreement. A majority of Canadians in a majority of the provinces, including a majority in Québec and a majority of Status Indians living on reserves, declined to provide such a mandate. Consequently, governments set aside the constitutional issue and announced their intention to concentrate on social and economic initiatives that do not require constitutional change.

Québec

Since September 1994, Québec has been governed by the Parti Québécois, whose platform calls for Québec’s accession to independence. On October 30, 1995, the government of Québec held a consultative referendum under provincial law, seeking a mandate to secede from Canada and proclaim Québec’s independence, after having made a formal offer of a new economic and political partnership between Québec and the rest of Canada. The government’s proposal was rejected by a vote of 50.6% against and 49.4% in favour, with a participation rate of 93%. While all sides accepted the 1995 referendum results, the Parti Québécois has not abandoned the goal of achieving independence for Québec.

The Government of Canada and the governments of a number of provinces outside Québec have taken a series of initiatives since the 1995 referendum aimed at reinforcing Canadian unity, including non-constitutional measures (notably on provincial responsibility for labour market programs), demonstrating openness to Québecers’ aspirations, as well as making efforts to clarify the rules governing any future referendum and the possible consequences of a Québec secession.

4

Table of Contents

In September 1996, the Government of Canada referred a series of legal questions to the Supreme Court of Canada with a view to clarifying, at both domestic and international law, whether the government of Québec has the right to secede from Canada unilaterally. On August 20, 1998, the Supreme Court rendered judgment, ruling that the government of Québec cannot, under either the Constitution of Canada or international law, legally effect the unilateral secession of Québec from Canada. The Supreme Court also stated that, if a clear majority of Québecers were to clearly and unambiguously express their will to secede, all governments in Canada would then have a constitutional obligation to enter into negotiations to address the potential act of secession as well as its possible terms should, in fact, secession proceed.

On June 29, 2000, the Government of Canada enacted a law to give effect to the requirement for clarity set out in the opinion of the Supreme Court. That law requires the House of Commons to assess, prior to any future referendum on the secession of a province, whether the referendum question made clear that the province would cease to be part of Canada and become an independent country. The law further requires that, after the vote itself, the House of Commons also assess whether there appeared to be a clear majority in support of the question. Only if both these conditions were met would the Government of Canada be authorized to enter into negotiations which might lead to the constitutional amendments required to effect secession.

In September 1997, the Premiers of the nine provinces other than Québec met in Calgary to launch public consultations on a set of declaratory principles, including a recognition of the unique character of Québec society within Canada, which seek to frame the fundamental values underlying the Canadian federation. Over the winter and spring of 1998, the legislatures of all nine provinces participating in the Calgary process passed resolutions of support for the principles set out in the Calgary declaration.

On November 30, 1998, the Parti Québecois government was re-elected with a majority of seats (75 out of 125) in Québec’s National Assembly, though with a vote count of 42% of the votes cast, slightly below that received by the main opposition party, the federalist Liberal Party of Québec, which won 48 seats. A third party, the Action Démocratique du Québec, which advocates a moratorium on further referenda on secession, took 12% of the votes cast and won 1 seat.

5

Table of Contents

THE CANADIAN ECONOMY*

General

The following chart shows the distribution of real gross domestic product (“GDP”) at basic prices (1997 constant dollars) in 2001, which is indicative of the structure of the economy.

DISTRIBUTION OF REAL GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT AT BASIC PRICES(1)

(1) GDP is a measure of production originating within the geographic boundaries of Canada, regardless of whether factors of production are Canadian or non-resident owned, whereas gross national product (“GNP”) measures the value of Canada’s total production of goods and services — that is, the earnings of all Canadian owned factors of production. Quantitatively, GDP is obtained from GNP by adding investment income paid to non-residents and deducting investment income received from non-residents. GDP at basic prices represents the value added by each of the factors of production and is equivalent to GDP at market prices less indirect taxes (net), plus other production taxes (net). Moreover, these differences in GDP measures explain any perceived discrepancies in GDP growth rates in this document.

(2) May not add to 100.0% due to rounding.

(3) The agriculture, forestry, fishing, hunting, mining and oil and gas extraction sectors include a service component.

The volume of industry and sector output in the following discussion provides “constant dollar” measures of the contribution of each industry to GDP at basic prices. The share of service-producing industries in real GDP was 68.7% in 2001 while the remaining 31.3% was attributed to goods-producing industries.

| * | Annual figures and year-over-year changes are based upon data that are not seasonally adjusted, except where otherwise indicated. Quarterly and semi-annual figures or changes are based upon seasonally adjusted data, except where otherwise indicated. |

6

Table of Contents

The following table shows the composition of Canada’s real GDP at basic prices (1997 constant dollars) by sector in 1987 and over the 1997-2001 period.

REAL GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT AT BASIC PRICES BY INDUSTRY

| For the years ended December 31, | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2001 | 2000 | 1999 | 1998 | 1997 | 1987(2) | 2001 | 1997 | 1987(2) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (millions of 1997 dollars) | (percentage distribution) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Agriculture

|

$ | 14,617 | $ | 15,975 | $ | 16,437 | $ | 15,230 | $ | 14,016 | $ | 12,090 | 1.5 | % | 1.7 | % | 1.8 | % | |||||||||||||||||||

|

Forestry, fishing and hunting

|

6,593 | 6,905 | 6,675 | 6,466 | 6,411 | 8,149 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 1.2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Mining and oil and gas extraction

|

37,062 | 36,461 | 33,901 | 34,461 | 33,935 | 25,971 | 3.9 | 4.2 | 3.9 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Manufacturing

|

160,935 | 168,825 | 160,150 | 149,390 | 142,282 | 112,727 | 17.0 | 17.4 | 17.1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Construction

|

50,346 | 48,498 | 46,529 | 44,348 | 42,995 | 44,241 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 6.7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Utilities

|

27,288 | 27,960 | 26,705 | 26,140 | 26,685 | 23,010 | 2.9 | 3.3 | 3.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Transportation and warehousing

|

44,531 | 45,265 | 43,306 | 41,036 | 40,337 | 31,112 | 4.7 | 4.9 | 4.7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Wholesale and retail trade

|

107,243 | 104,256 | 98,508 | 92,644 | 85,946 | 69,290 | 11.3 | 10.5 | 10.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Finance, insurance, real estate and leasing

|

186,989 | 180,834 | 174,227 | 166,070 | 161,097 | 116,387 | 19.7 | 19.7 | 17.7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Public administration and defence

|

53,826 | 52,057 | 51,082 | 50,249 | 49,482 | 44,137 | 5.7 | 6.1 | 6.7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Community, business and personal services

|

258,678 | 248,390 | 236,044 | 222,929 | 213,622 | 172,959 | 27.3 | 26.2 | 26.3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

TOTAL (1)

|

$ | 948,108 | $ | 935,426 | $ | 893,564 | $ | 848,963 | $ | 816,808 | $ | 658,425 | 100.0 | % | 100.0 | % | 100.0 | % | |||||||||||||||||||

Source: Statistics Canada, Input Output Division.

(1) May not add to total due to rounding.

(2) Data does not add to total due to rebasing.

The share of service-producing industries in real GDP at basic prices increased from 65.7% in 1987 to 68.7% in 2001. The fastest growing groups in this sector have been wholesale and retail trade and finance, insurance, real estate and leasing which both grew at average annual rates of 3.3% and 3.5%, between 1987 and 2001, compared to an average annual growth rate of 2.7% for total real GDP (1997 constant dollars). The goods-producing sector constituted 31.3% of real GDP at basic prices in 2001, down from 34.2% in 1987. The decline was most evident in construction with its share declining from 6.7% to 5.3%, and in utilities, where the share fell from 3.5% to 2.9%.

Real GDP growth was 3.9% in 1998, 5.2% in 1999 and 4.6% in 2000, while manufacturing output growth exceeded total output growth over this period, increasing by 4.9% in 1998, 7.2% in 1999 and by 4.7% in 2000. Total year-over-year GDP growth slowed in 2001, increasing by 1.4%, but has rebounded in 2002 to date, increasing by 1.9%, 2.5% and 3.6% in the first, second and third quarter respectively. On a year-over-year basis, manufacturing output contracted by 4.6% in 2001, and by 1.3% in the first quarter of 2002, before rising by 1.2% and 5.0% in the second and third quarter respectively.

The construction sector was the second largest goods-producing sector in Canada in 2001. Construction activity rose by 3.3% in 1998, 4.7% in 1999, 4.2% in 2000 and 3.9% in 2001. Construction output grew 4.4% year-over-year in the first quarter of 2002, 4.7% in the second quarter and 5.5% in the third quarter.

Output from mining and oil and gas extractions increased at a rate of 1.5% in 1998. Output fell by 0.7% in 1999, rebounded by 7.8% in 2000 and moderated to 1.7% in 2001. In 2002, year-over-year growth fell by 1.1% in the first quarter, 2.9% in the second quarter and 0.6% in the third quarter.

Although the share of agricultural output in total real GDP in 2001 was 1.5%, agriculture is an important part of Canada’s economy and a significant contributor to foreign exchange earnings. Wheat is Canada’s principal agricultural crop and one of its largest export products by value. The wheat crop was 24.3 million tonnes in the 1997-98 crop year, 24.1 million tonnes in the 1998-1999 crop year, 26.9 million tonnes in the 1999-2000 crop year and 26.5 million tonnes in the 2000-2001 crop year. Total wheat production fell to 20.6 million tonnes in the 2001-2002 crop year. Statistics Canada estimates that the 2002-2003 crop year will be one of the worst growing seasons in recent history in Western Canada with wheat production estimated at only 15.5 million tonnes due to exceptionally dry conditions.

| * | Unless otherwise specified, all growth rates are calculated using real GDP at basic prices, 1997 chained dollars. All percentage changes are compounded at annual rates. For percentage changes over more than one year the method of computation utilizes observations for the first and final years indicated. For percentage changes over less than one year the method of calculation utilizes observations for the period stated and the previous period of the same length. |

7

Table of Contents

Gross Domestic Income and Expenditure

Real GDP continued to trend upward from 1997 to 2000, growing by 4.2% in 1997, 4.1% in 1998, 5.4% in 1999, and 4.5% in 2000, while nominal GDP grew by 5.5% in 1997, 3.7% in 1998, 7.2% in 1999 and 8.6% in 2000. Real and nominal GDP growth tapered off in 2001 increasing by 1.5% and 2.6% respectively. In the first three quarters of 2002, real GDP rebounded by 2.1%, 3.1% and 4.0% respectively (year-over-year); nominal GDP growth was 0.5%, 3.4% and 6.1% respectively.

GROSS DOMESTIC INCOME AND EXPENDITURE

| First 3 quarters (10) | For the years ending December 31, | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2002 | 2001 | 2001 | 2000 | 1999 | 1998 | 1997 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (in millions of dollars) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

INCOME

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Labor income (1)

|

$ | 590,485 | $ | 567,163 | $ | 568,864 | $ | 545,110 | $ | 502,726 | $ | 475,335 | $ | 453,073 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

Corporate profits (2)

|

121,197 | 123,876 | 118,227 | 129,821 | 108,745 | 86,132 | 87,932 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Non-farm unincorporated business income

|

71,745 | 66,104 | 66,551 | 63,962 | 61,351 | 57,936 | 54,663 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Farm income

|

1,977 | 2,976 | 2,972 | 1,758 | 1,935 | 1,724 | 1,663 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other net domestic income (3)

|

58,155 | 65,171 | 63,386 | 62,334 | 53,887 | 53,461 | 54,911 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Net domestic income

|

896,588 | 877,841 | 872,577 | 854,701 | 779,285 | 723,487 | 700,063 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Indirect taxes, capital consumption

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

allowances and residual error

|

235,445 | 217,973 | 219,669 | 210,294 | 201,239 | 191,486 | 182,670 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

GROSS DOMESTIC INCOME

|

$ | 1,132,033 | $ | 1,095,814 | $ | 1,092,246 | $ | 1,064,995 | $ | 980,524 | $ | 914,973 | $ | 882,733 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

EXPENDITURE

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Consumer expenditure

|

$ | 645,739 | $ | 618,723 | $ | 620,777 | $ | 594,089 | $ | 560,954 | $ | 531,169 | $ | 510,695 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

Government expenditure

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

(goods & services):

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Federal (4)

|

45,864 | 42,599 | 43,168 | 41,599 | 38,160 | 35,250 | 34,011 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Provincial-municipal (5)

|

196,149 | 186,615 | 187,898 | 178,217 | 169,741 | 164,086 | 157,854 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Total government (6)

|

242,013 | 229,213 | 231,066 | 219,816 | 207,901 | 199,336 | 191,865 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

of which current

|

212,763 | 203,111 | 204,492 | 196,004 | 185,317 | 179,317 | 171,756 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

of which capital (7)

|

29,251 | 26,103 | 26,574 | 23,812 | 22,584 | 20,019 | 20,109 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Residential construction

|

61,508 | 51,080 | 52,154 | 48,566 | 45,917 | 42,497 | 43,519 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Business fixed investment:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Non-residential construction

|

51,044 | 52,427 | 52,268 | 50,890 | 46,816 | 45,177 | 43,872 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Machinery and equipment

|

84,405 | 87,277 | 85,504 | 86,693 | 79,977 | 74,116 | 67,346 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Total

|

135,449 | 139,704 | 137,772 | 137,583 | 126,793 | 119,293 | 111,218 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Inventory accumulation:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Business non-farm

|

2,151 | -1,996 | -4,740 | 8,189 | 4,932 | 5,409 | 9,174 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Farm

|

-1,311 | -1,275 | -1,300 | -161 | 55 | -676 | -1,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Total

|

840 | -3,271 | -6,040 | 8,028 | 4,987 | 4,733 | 8,174 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Exports (goods & services) (8)

|

467,080 | 482,611 | 473,000 | 484,331 | 421,796 | 379,203 | 348,604 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Imports (goods & services) (9)

|

-419,417 | -422,591 | -416,498 | -428,934 | -388,157 | -360,871 | -331,271 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Residual error of estimate

|

-1,179 | 345 | 15 | 1,516 | 333 | -387 | -71 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

GROSS DOMESTIC EXPENDITURE

|

$ | 1,132,033 | $ | 1,095,815 | $ | 1,092,246 | $ | 1,064,995 | $ | 980,524 | $ | 914,973 | $ | 882,733 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

GROSS DOMESTIC EXPENDITURE IN 1997 CHAIN-FISHER

DOLLARS (11)

|

$ | 1,057,402 | $ | 1,025,802 | $ | 1,027,523 | $ | 1,012,335 | $ | 968,451 | $ | 918,910 | $ | 882,733 | ||||||||||||||||||

Source: Statistics Canada, National Income and Expenditure Accounts.

(1) Includes military pay and allowances.

(2) Includes net interest and dividends paid to non-residents.

(3) Includes interest, miscellaneous investment income and government business enterprise profits before taxes.

(4) Net spending (outlays minus sales) including gross capital formation and Canada Pension Plan.

(5) Net spending (outlays minus sales) including gross capital formation and Québec Pension Plan.

(6) Includes government inventories.

(7) Includes inventory accumulations at all levels of government.

(8) Excludes investment income received from non-residents.

(9) Excludes investment income paid to non-residents.

(10) Seasonally adjusted, annual rates.

| (11) | A new formula (Chain-Fisher) is now used to estimate the level of real GDP. This new formula replaces the previous Laspeyres formula. |

8

Table of Contents

Economic Developments*

Nominal GDP at market prices was about $1.1 trillion in 2001. Real output growth experienced gains of 4.2% in 1997, 4.1% in 1998, 5.4% in 1999 and 4.5% in 2000, before slowing to 1.5% in 2001. Year-over-year real GDP growth rebounded in 2002 to date, registering 2.1% in the first quarter, 3.1% in the second quarter and 4.0% in the third quarter.

Real consumer spending rose by 4.6% in 1997, 2.8% in 1998, 3.9% in 1999, 3.7% in 2000 and 2.6% in 2001. Year-over-year growth in consumer spending remained robust at 2.1% in the first quarter, 2.7% in the second quarter and 2.9% in the third quarter of 2002. The personal savings rate declined steadily between 1991 and 1997, after reaching a peak of 13.8% in 1991. In 2001, the personal savings rate was 4.6%, increasing to 5.3% in the first quarter of 2002 and 4.7% in both the second and third quarter of 2002.

Real non-residential business investment grew at its highest rate on record in 1997, rising 22.6% before slowing to 5.3% in 1998. Year-over-year growth in non-residential business investment was 7.8% in 1999, 8.2% in 2000 and fell by 1.1% in 2001. The strength in non-residential business investment over this period was largely due to strong increases in machinery and equipment investment. Year-over-year growth decreased by 5.2% in the first quarter of 2002, fell by 3.4% in the second quarter and 4.9% in the third quarter.

Housing starts have generally increased in recent years. However, the recent levels have tended to be below those reached in the 1980s. Housing starts rose to 148 thousand units in 1997, before dropping to 138 thousand units in 1998. Housing starts rebounded in 1999, registering 149 thousand units, and continued rising to 153 thousand units and 163 thousand units in 2000 and 2001 respectively. In the first three quarters of 2002, the level of housing starts expanded strongly to 204 thousand, 196 thousand and 206 units respectively.

Government spending on current goods and services contracted between 1994 and 1997 by an average of 0.9% annually. Growth was 3.2% in 1998, 1.9% in 1999, 2.3% in 2000 and 3.3% in 2001. Year-over-year growth in government spending on goods and services for 2002 was 2.5% in the first quarter, 2.0% in the second quarter and 2.2% in the third quarter.

In current dollar terms, the trade balance was $16.8 billion in 1997 and $17.4 billion in 1998 before rising rapidly to $33.1 billion in 1999, $54.7 billion in 2000 and 55.6 billion in 2001. For 2002 the surplus at annual rates on the foreign trade balance was $48.4 billion in the first quarter, $45.0 billion in the second quarter and $47.4 billion in the third quarter. (See also “Balance of Payments”.)

| * | In this section all figures are reported in real terms unless otherwise noted. |

9

Table of Contents

Prices and Costs

The year-over-year increase in the GDP implicit price deflator declined from 1.2% in 1997, to -0.5% in 1998, rebounding to 1.7% in 1999, 3.9% in 2000 and 1.0% in 2001. Year-over-year growth in the implicit price deflator fell by 1.6% for the first quarter of 2002, rose to 0.2% in the second quarter and increased further to 2.0% in the third quarter.

The year-over-year increase in the consumer price index (“CPI”) has been moderate since 1996, with increases of 1.6% in 1997, 0.9% in 1998 and 1.7% in 1999. After remaining below 2.0% during most of the 1990’s, the year-over-year increase in the CPI registered 2.7% in 2000 and 2.6% in 2001. The increase in 2000 is largely attributable to a surge in energy prices, while the increase observed in 2001 was more broadly-based. CPI inflation was lower in the first two quarters of 2002, at 1.5% and 1.3%, respectively, and edged up to 2.3% in the third quarter.

PRICE DEVELOPMENTS

| G.D.P. | Consumer Price Index | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Implicit | Industrial | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chain | Total | Total Excluding | Product | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| For the years | Price Index | Excluding | Food & | Shelter | Price | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ended December 31, | (1) | Total | Food | Food | Energy | Energy | Services | Index | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (annual percentage changes) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1997

|

1.2 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 1.6 | -0.2 | 0.7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1998

|

-0.5 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 0.9 | -4.0 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1999

|

1.7 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 5.7 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

2000

|

3.9 | 2.7 | 1.4 | 3.1 | 16.2 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 4.3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

2001

|

1.0 | 2.6 | 4.5 | 2.1 | 3.3 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 1.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

2001 Q4

|

-1.2 | 1.1 | 3,9 | 0.5 | -8.9 | 1.7 | 2.1 | -1.9 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

2002 Q1

|

-1.6 | 1.5 | 4.1 | 1.0 | -5.4 | 1.9 | 1.7 | -1.1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

2002 Q2

|

0.2 | 1.3 | 2.6 | 1.1 | -8.7 | 2.4 | 1.8 | -1.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

2002 Q3

|

2.0 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.4 | -1.6 | 3.0 | 1.8 | 0.3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||