TD Bank's very bad year in the Maritime seafood business

Despite failures of some companies, consultant says the sector is strong

A bankruptcy and insolvency court in Halifax granted Chester Basin Seafoods more time to restructure late last week in order to save its business exporting silver hake, a relative of cod.

The order approved a loan from the company founder to get two of its fishing boats out of a Meteghan shipyard where they are undergoing repairs.

Secured creditor Toronto-Dominion Bank reluctantly went along with reprieve. It was TD's decision earlier this month to call in $5.5 million in loans that triggered the creditor protection proceedings.

Chester Basin is the third seafood company to falter in 2023 with TD Bank as a secured creditor on loans totalling $39 million.

The bank did not directly answer when CBC asked if it would pull back from the sector given this failure and others.

'Where did all the money go'

"TD intends to continue providing access to financial services across our diverse customer base in all of the communities we serve," spokesperson David Maher said in an email.

In Halifax on Friday, TD lawyer Gavin MacDonald asked bankruptcy and insolvency registrar Raffi Balmanoukian "where did all [Chester Basin's] money go."

"There is next to nothing in working capital and two busted vessels."

MacDonald also said he was not "asserting anyone did anything wrong."

Other companies on the rocks

In March, another Nova Scotia silver hake processor, Meridien Atlantic and Rocky Coast Seafoods of Comeauville, was forced into receivership when TD called $6.6 million in loans.

Rocky Coast Seafoods of Comeauville N.S., was put into receivership in March. TD was a secured creditor owed $6-million. (Google Maps)

Rocky Coast Seafoods of Comeauville N.S., was put into receivership in March. TD was a secured creditor owed $6-million. (Google Maps)

In September, the bank forced the sale of P.E.I. lobster processor South Shore Seafoods and affiliated companies. TD was owed $27 million.

Despite these localized setbacks, the seafood industry is by far the most successful sector of the Atlantic economy over the last decade, says fishery policy consultant and author Rick Williams.

TD was owed $27 million by P.E.I. lobster processor South Shore Seafoods when it folded in September. (South Shore Seafood)

TD was owed $27 million by P.E.I. lobster processor South Shore Seafoods when it folded in September. (South Shore Seafood)

He predicts that is not going to change.

Value of seafood on the rise

"I think we'll continue to see a lot of investor interest in the fishery and we'll continue to see at the enterprise level a lot of investor interest in having access to licenses and quotas," Williams says.

Though fishery landings fell in the last decade, the overall value has increased, he said.

"I would not generalize from a very small unique fishery like silver hake. I wouldn't generalize from that to the overall fishering economy," he said.

1 ship ran aground, 2 others failed

As for Chester Basin Seafoods and its silver hake business, the company has until Jan. 21 to right the ship.

Its financial problems grew this year when all three of its fishing boats were suddenly put out of commission.

Seaman's Toy 1 ran aground and the other two experienced total engine failures. Fortune Pride and Atlantic Sea Clipper remain at the AF Theriault Shipyard.

Jose

Teixiera of Chester Basin Seafoods in court last Friday trying to keep

the insolvent Nova Scotia silver hake exporter afloat. It is one of

three seafood companies that faltered owing TD Bank nearly $40-million

in 2023. (Paul Withers/CBC)

Jose

Teixiera of Chester Basin Seafoods in court last Friday trying to keep

the insolvent Nova Scotia silver hake exporter afloat. It is one of

three seafood companies that faltered owing TD Bank nearly $40-million

in 2023. (Paul Withers/CBC)

In October, Chester Basin founder Jose Teixeira personally advanced $200,000 to make partial payment for repairs to Seaman's Toy 1 so it would be released from the boatyard and the company would have one vessel out fishing.

Teixeira sold the company last year and is now a minority owner

He is lending the company $1.1 million at 18 per cent interest in what's known as debtor in place, or DIP, financing to try to save the business. The financing was approved Friday by insolvency registrar Balmanoukian.

Teixeira declined comment after the hearing on Friday, as did TD's lawyer.

Review of Current Investigations and Regulatory Actions Regarding the Mutual Fund Industry Thursday, November 20, 2003

Too funny

New law proposed to shift bank failure risk from taxpayers

Ottawa proposes 'bail-in' regime to force creditors to prop up failing banks

Thomson Reuters · Posted: Mar 23, 2016 2:14 PM ADT

The Liberal government says it will create legislation that shifts some of the risk in a bank failure to creditors. (Canadian Press)

Canada will introduce legislation to implement a "bail-in" regime for systemically important banks that would shift some of the responsibility for propping up failing institutions to creditors.

The proposed plan outlined in the federal budget released on Tuesday would allow authorities to convert eligible long-term debt of a failing lender into common shares in order to recapitalize the bank, allowing it to remain operating.

Royal Bank of Scotland bailout: 10 years and counting

Published Friday, 12 October, 2018

Ten years after the crisis that led to the bailout of the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), the Government still owns 62% of the bank. It could be another seven years before the last publicly-owned share is sold.

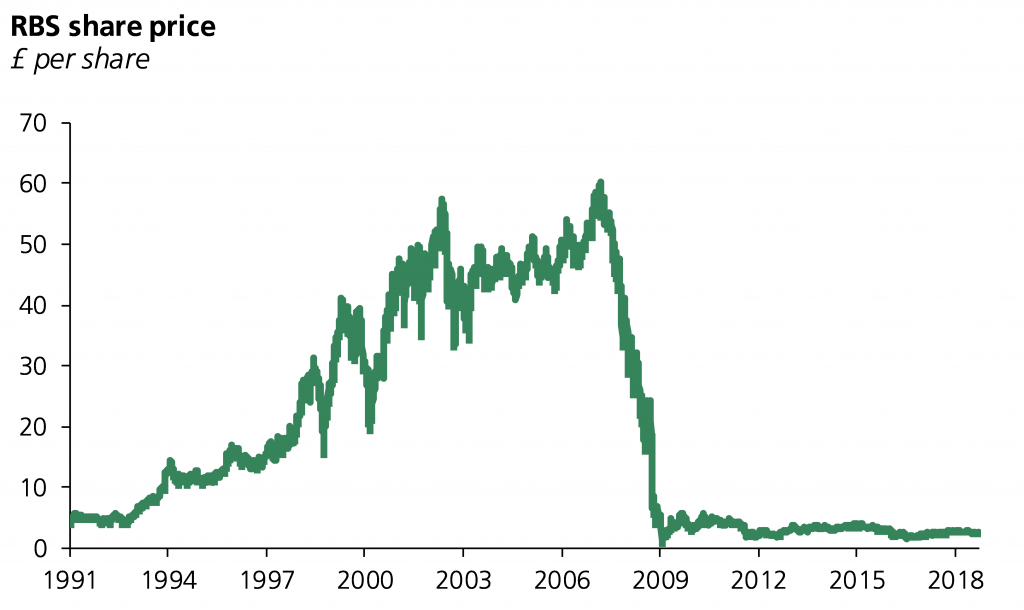

In the course of 2008, as the financial crisis gathered speed, RBS shares lost 87% of their value.

The most eventful day for RBS that year was 7 October. On that Tuesday morning, RBS’s CEO, Fred Goodwin, was giving a presentation about the bank’s opportunities ahead. By the time he’d finished speaking, the share price had plunged 35%. Later that morning, the Chairman of RBS, Sir Tom McKillop called the then Chancellor, Alistair Darling, to tell him RBS was going to run out of money the same afternoon. Darling asked the Bank of England to make emergency loans to RBS, and tens of billions of dollars and pounds were made available covertly.

As speculation mounted that the Government was going to buy fresh shares of RBS (to ‘recapitalise’ it), the bank stated it was making no such request from Government. A long night at the Treasury ensued for Goodwin and fellow CEOs from the largest UK banks. Goodwin initially resisted the bailout that would end his tenure at the helm of RBS, but eventually relented in the early hours of 8 October 2008. That morning the Treasury announced it was making £25 billion of capital available to the banks, £20 billion of which would turn out to be for RBS.

Following a second bailout in December 2009, taking the total to £46 billion, the public found itself owning 84% of the bank.

Why, ten years on, does the British public still own 62% of RBS? In short: nobody likes losses, including the Government.

$25B credit backstop for banks 'not a bailout': Harper

'Market transaction' will cost government nothing, Tory leader says

CBC News · Posted: Oct 10, 2008 9:08 AM ADT

The federal government's $25-billion takeover of bank-held mortgages to ease a growing credit crunch faced by the country's financial institutions is not a bailout similar to recent moves made in the United States and other Western countries, Conservative Leader Stephen Harper said Friday.

"This is not a bailout; this is a market transaction that will cost the government nothing," he told reporters at a campaign rally in Brantford, Ont., ahead of Tuesday's federal election.

"We are not going in and buying bad assets. What we're doing is simply exchanging assets that we already hold the insurance on and the reason we're doing this is to get out in front. The issue here is not protecting the banks."

Earlier in the day, Finance Minister Jim Flaherty announced the government's plan to buy the securities through the Canada Housing and Mortgage Corp. and provide much-needed cash to financial institutions that sell the so-called "National Housing Act mortgage-backed securities."

Reply to Ron Eaton

Moody's cuts bank outlook to 'negative' on Ottawa's bail-in rule

Credit ratings agency says risk of failure is remote, but it prefers option of taxpayer bailout

CBC News · Posted: Jul 08, 2014 4:02 PM ADT | Last Updated: July 8, 2014

Moody's Investors Service lowered the outlook for Canada's banks to negative from stable in a report Tuesday, citing Ottawa's 'bail-in' law. (Mark Lennihan/Associated Press)

Investor ratings service Moody’s has changed its outlook for Canada’s biggest banks to negative from stable, citing concerns over the Canadian government’s plan to implement a “bail-in” system in the event of a bank failure.

The “bail-in” rule, included as part of the 2013 omnibus budget bill, asserts that the federal government would not necessarily bail out a bank on the brink of failure with taxpayer money.

Instead bank bondholders would be expected to assume the risk, though there is no guarantee that deposit-holders would not be hurt if they had more money in the bank than the $100,000 guaranteed by CDIC.

Reply to Peter Freeland

Offshore banking accounts?

He is lending the company $1.1 million at 18 per cent interest in what's known as debtor in place, or DIP, financing to try to save the business. "

Chester Basin (as a company) never HAD any money since the owner sold. As a minority shareholder now, Teixeira is already forking over $1.1 million of his own money he may never see again and it's no one's business WHAT he did with any more money he may have earned from the company sale.

okay at least, Enforce the Law or tighten up the Law ...

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)

200 Nautical Mile Limit ...

Canada is one of the better countries in terms of enforcing quotes and regulating equipment and fishing practices, but globally our oceans are in big trouble and no one seems to be in much of a rush to do anything about it.

The free-for-all attitude on the high seas is having major impacts over the long run and "the price of fish" will be the least of anyone's worries.

And you based your not so expert opinion on a sample size of 3 loans in a portfolio of loans that guns into the hundreds of billions of dollars. As a TD shareholder, I’ll value their input over yours.

Scotiabank profit falls as bank sets aside almost $1.3B to cover bad loans

Costs increased far more than revenue did

The bank reported its net income was $1.39 billion for the three-month period up until the end of October. That's down by more than a third from the $2.09 billion it earned the same time last year.

Revenue came in at $8.31 billion, up from nearly $7.63 billion last year. But the bank was making less money because its costs rose by even more.

The bank's expenses rose to $5.5 billion during the quarter, an increase of 22 per cent. The bank attributed its surging costs to "higher personnel costs, technology-related costs, performance-based compensation, business and capital taxes, share-based compensation, advertising and the unfavourable impact of foreign currency translation."

In October, the bank announced it was laying off about three per cent of its workforce to rein in costs. On Tuesday the bank revealed it recorded a restructuring and severance charge of $354 million related to those moves.

The bank said it had 89,483 employees at the end of the quarter, down about 1,500 from the previous quarter or a little over halfway to its three per cent reduction target.

The bank also said it took an $89 million charge related to reducing its real estate footprint, and plans to close some branches. The bank said it had 2,379 branches and offices at quarter end, down 19 from three months earlier., though none of the branch closures it announced in the quarter have happened yet because of rules around giving months of notice to communities.

The bank didn't provide clarity in the quarter around how many branches in total it plans to shut, though it did confirm it would close eight branches in Newfoundland as part of a consolidation across various markets in Canada.

Another major drag on the company's earnings was money it sets aside to cover bad loans, a closely watched financial metric known as provisions for credit losses.

The bank set aside more than $1.2 billion to cover such loans during the quarter. That's more than double the $529 million worth of provisions it had this time last year.

Within that, the bank set aside $454 million to cover loans that are currently performing fine. That's sharply up from $35 million of such loans last year.

The rest — $802 million — was for loans that are already underperforming, which means they aren't being paid back as planned. That figure was $494 million last year.

"The increased provision this quarter was driven primarily by the unfavourable macroeconomic outlook and uncertainty around the impacts of higher interest rates," the bank said of its higher loan losses.

Mario Mendonca, an analyst with TD Bank who covers Scotia, says the increase in impaired loans "suggests

conditions are deteriorating in Canadian personal loans and unsecured lines."

The bank had $498 million worth of residential mortgages that were "non-performing" at the end of October. That's up from $406 million a year ago but still a tiny percentage of their overall home loan portfolio, which came in at $271 billion during the quarter. That's a decline of four per cent or $11 billion from just over $282 billion a year ago.

"Mortgage delinquencies ticked higher, but remain low," Mendonca said.

Investors did not respond kindly to Scotiabank's financial results, with the shares losing about five per cent of their value to trade at just over $57 apiece when the Toronto Stock Exchange opened for trading on Tuesday.

Scotiabank is the first of the Big 6 lenders to reveal quarterly financial results in the coming days. Royal Bank, TD and CIBC will reveal their numbers on Thursday, followed by Bank of Montreal and National Bank on Friday.

Barry Schwartz, chief investment officer at Baskin Wealth Management, says he expects the rest of the bank's to show similarly gloomy numbers.

"I think you'll see other Canadian banks also increase reserves against future losses," he said in an interview with CBC News. "It's not a good look overall for the Canadian banks as we head into 2024. All we can hope for is that we escape a recession or it's very mild and that rates do get cut in the next three to six months."

With files from The Canadian Press and the CBC's Meegan Read

$25B credit backstop for banks 'not a bailout': Harper

'Market transaction' will cost government nothing, Tory leader says

The federal government's $25-billion takeover of bank-held mortgages to ease a growing credit crunch faced by the country's financial institutions is not a bailout similar to recent moves made in the United States and other Western countries, Conservative Leader Stephen Harper said Friday.

"This is not a bailout; this is a market transaction that will cost the government nothing," he told reporters at a campaign rally in Brantford, Ont., ahead of Tuesday's federal election.

"We are not going in and buying bad assets. What we're doing is simply exchanging assets that we already hold the insurance on and the reason we're doing this is to get out in front. The issue here is not protecting the banks."

Earlier in the day, Finance Minister Jim Flaherty announced the government's plan to buy the securities through the Canada Housing and Mortgage Corp. and provide much-needed cash to financial institutions that sell the so-called "National Housing Act mortgage-backed securities."

Flaherty announced the new measures in an attempt to assuage concerns over the burgeoning global financial crisis and defuse criticism that the Harper government was ignoring the spreading lending crisis.

Dealing with Armageddon

Governments in many countries have been grappling with how to stop the deterioration in the health of financial institutions as companies are forced to write off billions in losses from holdings of now worthless asset-backed commercial paper.

However, Canada's market for insured mortgage pools still functions.

<a href="http://www.cbc.ca/news/yourvoice/"><img src="http://www.cbc.ca/news/yourvoice/img/yourvoice-sidebar-header.jpg"></a><br>[/CUSTOM]

‘Didn't Harper just say we would never need this kind of thing? Isn't he supposed to be an economist?’

— R Gerald

<a href=http://www.cbc.ca/money/story/2008/10/10/flaherty-banks.html#articlecomments#postc>Add your comment</a>[/CUSTOM]

In addition, many of the mortgages that are bundled together to make up these securities are not in default, unlike the situation in the United States. For instance, in the second quarter of 2008, the percentage of American mortgages that were more than 90 days in arrears — a measure of the level of home defaults — stood at a gaudy 4.5 per cent. In Canada, that same figure stood at 0.3 per cent.

The specialized housing securities, both in Canada and the United States, generate cash based upon the stream of payments from the underlying mortgages. High default rates mean these bonds cannot produce a sufficient amount of cash for investors.

That was what caused the asset-backed market in United States to collapse.

Canada does not face the same problem, Flaherty insisted.

Instead, the country's financial companies are having trouble getting money to borrow because banks and other lenders in other countries are not offering up enough money — a classic credit crunch.

After the announcement, Canada's leading banks said they were cutting their prime rates by 15 or 25 basis points — a quarter or fifteen-one-hundredths of a percentage point.

Greasing Canada's financial system

Under the proposal, Ottawa plans to sell a combination of government bonds and other public debt instruments to raise the $25 billion. Then CMHC will ask the banks and other financial institutions to ascertain how much debt they would like to sell to the agency, using a process known as a reverse auction.

Conceptually speaking, the financial companies will offer CMHC the debt at a discount to its face value. Starting with the bids containing the largest discounts, the housing corporation will buy these instruments from the financial institutions until the agency uses up the $25 billion.

This way, Ottawa injects money into a cash-strapped market. In return, the government gets a series of securities with a rate of return well in excess of the rate Ottawa would pay on the $25 billion it borrows in the first place.

The federal government anticipates that few of these mortgages will default, and most are guaranteed by the CMHC. Thus, Ottawa actually expects to earn a profit from its holdings of these securities.

"This program is an efficient, cost-effective and safe way to support lending in Canada that comes at no fiscal cost to taxpayers," Flaherty said.

Flaherty said the action would "make loans and mortgages more available and more affordable for ordinary Canadians and businesses."

On Thursday, Flaherty said he had no doubts over the health of Canada's banks, adding the government has no plan to undertake a massive government bailout similar to those mounted by the United States and other Western countries.

He repeated that theme on Friday, saying the problem the country's financial institutions face is not solvency but the availability of credit.

"It is important to underline that Canada’s banks and other financial institutions are sound, well-capitalized and less leveraged than their international peers. Our mortgage system is sound. Canadian households have smaller mortgages relative both to the value of their homes and to their disposable incomes than in the U.S.," Flaherty said.

Royal Bank of Scotland bailout: 10 years and counting

It could be another seven years before the last publicly-owned share is sold.

Ten years after the crisis that led to the bailout of the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), the Government still owns 62% of the bank. It could be another seven years before the last publicly-owned share is sold. Here we explore why.

The fall

In the course of 2008, as the financial crisis gathered speed, RBS shares lost 87% of their value.

Source: Bloomberg

The most eventful day for RBS that year was 7 October. On that Tuesday morning, RBS’s CEO, Fred Goodwin, was giving a presentation about the bank’s opportunities ahead. By the time he’d finished speaking, the share price had plunged 35%. Later that morning, the Chairman of RBS, Sir Tom McKillop called the then Chancellor, Alistair Darling, to tell him RBS was going to run out of money the same afternoon. Darling asked the Bank of England to make emergency loans to RBS, and tens of billions of dollars and pounds were made available covertly.

As speculation mounted that the Government was going to buy fresh shares of RBS (to ‘recapitalise’ it), the bank stated it was making no such request from Government. A long night at the Treasury ensued for Goodwin and fellow CEOs from the largest UK banks. Goodwin initially resisted the bailout that would end his tenure at the helm of RBS, but eventually relented in the early hours of 8 October 2008. That morning the Treasury announced it was making £25 billion of capital available to the banks, £20 billion of which would turn out to be for RBS.

Following a second bailout in December 2009, taking the total to £46 billion, the public found itself owning 84% of the bank.

The road to recovery

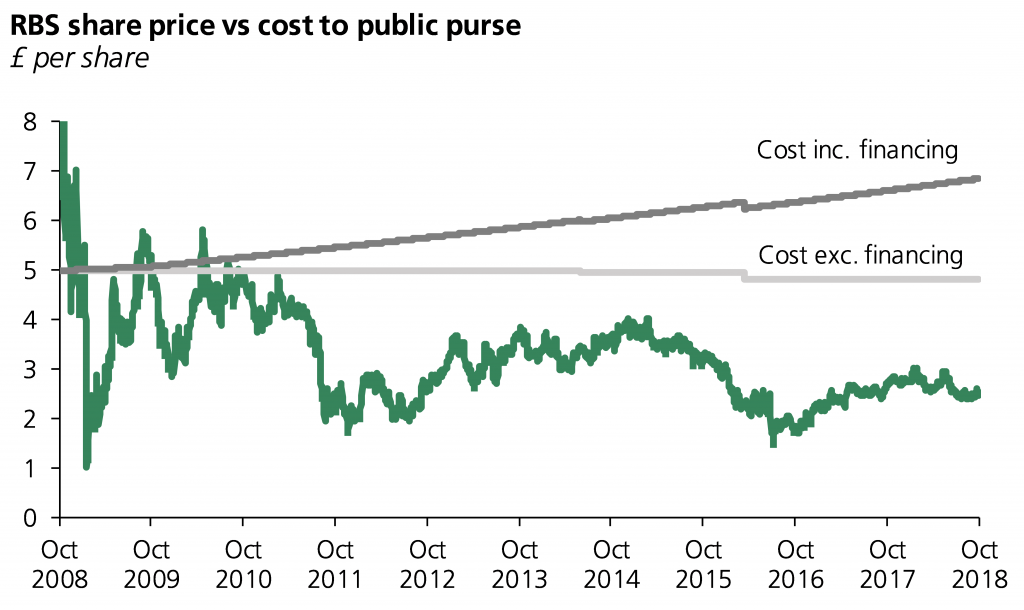

Why, ten years on, does the British public still own 62% of RBS? In short: nobody likes losses, including the Government.

After the bailouts, the RBS share price fell below what the Government paid, and has not come anywhere near since (see chart below). Why has the share price remained low? Well, RBS hasn’t been a very attractive investment since it crashed. It made a £24 billion loss in 2008, and has been loss-making every year since, until 2017. This 12 October 2018, RBS finally pays its first dividend to ordinary shareholders since 2008. RBS is also a very different bank today: 70% smaller by balance sheet size.

The Government had hoped the bank would return to steady profits more quickly, and that the share price would rise as a result. This hasn’t happened yet. The Government could decide to wait for as long as it takes for the shares to rise above what was paid in 2008-2009, but waiting is not free: there is a ‘financing cost’ to holding the shares. For example, Government funds tied up in RBS shares could be used instead to reduce the national debt, or to invest in infrastructure.

The chart below shows the difference between what the shares are worth and the cost to the public purse. The cost to the Treasury of RBS shares grows steadily as time passes, once financing costs are included. This is shown by the dark grey line on top. Holding the shares until the price rises above cost means waiting for the green line to catch up with the dark grey line (minus future dividends). It might take many years, and there is no guarantee it will ever happen.

Source: Bloomberg; Library calculations based on NAO report, The first sale of shares in Royal Bank of Scotland (July 2017)

Note: Dividends received are deducted from cost

And so, there are no simple solutions. The Government started selling at a loss. It sold at 330p per share in August 2015 and 271p per share in June 2018, compared with a cost per share of 499p (excluding financing).

Government plans laid out in March 2018 are to continue selling around £3 billion worth of shares every year until 2022-23. At that rate, the last RBS shares will be sold in 2025 – 17 years after the first bailout.

For now, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) estimates that saving RBS cost the public £27 billion. The final figure will depend on how the share price does in the next few years. If the shares go up faster than financing costs, the loss will be smaller; it will be larger if the shares continue to languish.

For more information about the rescue of RBS and other banks, read our briefing about the Bank rescues of 2007-09: outcomes and cost.

Federico Mor is a Senior Library Clerk at the House of Commons Library, specialising in business and finance.

No comments:

Post a Comment